There are many adjectives used to describe the taste of different kinds of cheese: mild, tangy, buttery, nutty, sharp, smoky, I could continue but I won’t. Our preferences between these different characteristics will then drive what cheese we look for in stores and buy. But I would wager that most people (or dare I say anyone?) are rarely looking for a bitter cheese. I had never thought about how cheese could be bitter; probably because it’s something that I’ve never tasted before and that’s because the cheese production industry actively works to prevent cheese from being bitter. Intrigued? Good, because our guest this week researches why and how cheese can become bitter.

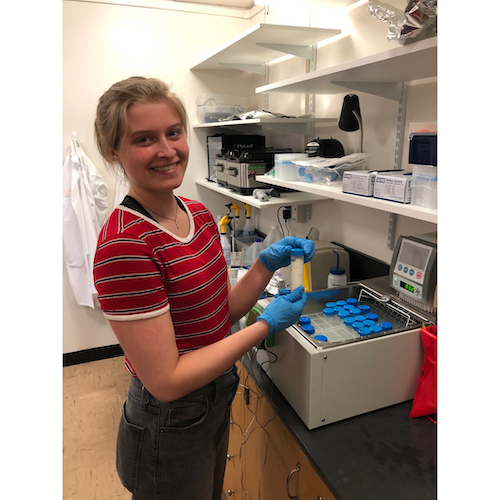

Paige Benson is a first year Master’s student advised by Dr. David Dallas in the Food Science Department. For her research, Paige is trying to understand how starter cultures affect the bitterness in aged gouda and cheddar cheeses. The cheese-making process begins with ripening milk, during which milk sugar is converted to lactic acid. To ensure that this process isn’t random, cheese makers use starter cultures of bacteria to control the ripening process. The bitterness problems don’t appear until the very end when a cheese is in its aging stage, which can take anywhere from 0-90 days. During this aging process, casein proteins (one of the main proteins in milk and therefore cheese) are being broken down into smaller peptides and it’s during this step that bitterness can arise. Even though this bitter cheese problem has been widely reported for decades (probably centuries), there are many different hypotheses about what causes the bitterness. Some say it might be the concentration of peptides, while others believe it’s a result of the starter culture used, and a third school of thought is that it’s the specific types of peptides. Paige is trying to bring some clarity to this problem by focusing on the bitterness that might be coming from the peptides.

To accomplish this work, Paige will be making lots of mini cheeses from different starter cultures, then aging them and extracting the peptides from the cheese to investigate the peptide profiles through genome sequencing. Scaling down the size of the cheeses will allow Paige to investigate starter cultures in isolation as well as in combination with different strains to see how this may affect peptide profiles, and therefore potentially bitterness.

Besides Paige’s research in cheese, we will also be discussing her background which also features lots of dairy! As a Minnesotan, Paige grew up surrounded by the best of the best dairy. In fact, her grandparents owned and ran a dairy farm, where Paige spent many of her summers and holidays. Her passion for food science was solidified when she started working as an organic farmer during her senior year of high school and she hasn’t ever looked back. Join us on Sunday, April 16th at 7 pm live on 88.7 FM or on the live stream. Missed the live show? You can listen to the recorded episode on your preferred podcast platform!