This week we have a robotics PhD student, Everardo Gonzalez, joining us to discuss his research on coordinating robots with artificial intelligence (AI). That doesn’t mean he dresses them up in matching bow ties (sadly), but instead he works on how to get a large collective of robots, also called a swarm, to work collectively towards a shared goal.

Why should we care about swarming robots?

Aside from the potential for an apocalyptic robot world domination, there are actually many applications for this technology. Some are just as terrifying. It could be applied to fully automated warfare – reducing accountability when no one is to blame for pulling the trigger (literally).

However, it could also be used to coordinate robots used in healthcare and with organizing fleets of autonomous vehicles, potentially making our lives, and our streets, safer. In the case of the fish-inspired Blue Bots, this kind of coordinated robot system can also help us gather information about our oceans as we try to resolve climate change.

#Influencer

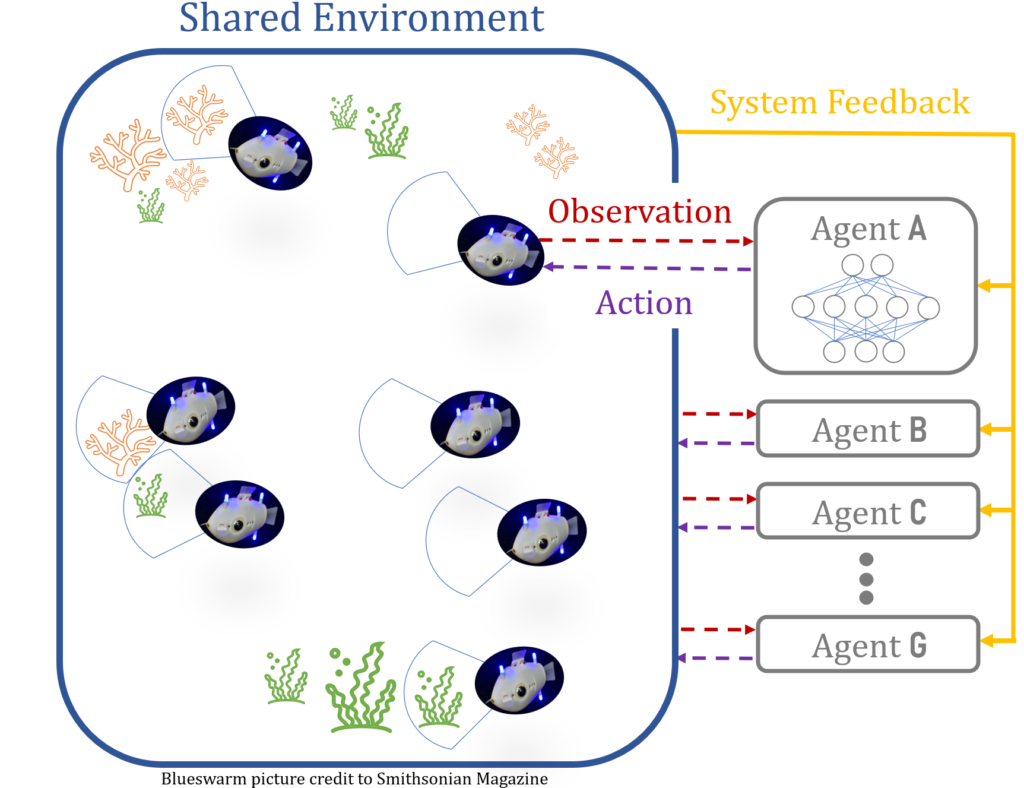

Having a group of intelligent robots behaving intelligently sounds like it’s a problem of quantity, however, it’s not that simple. These bots can also suffer from there being “too many cooks in the kitchen”, and, if all bots in the swarm are intelligent, they can start to hinder each other’s progress. Instead, the swarm needs both a few leader bots, that are intelligent and capable of learning and trying new things, along with follower bots, which can learn from their leader. Essentially, the bots play a game of “Follow the Leaders”.

All robots receive feedback with respect to a shared objective, which is typical of AI training and allow the bots to infer which behaviors are effective. In this case, the leaders will get additional feedback on how well they are influencing their followers.

Unlike social media, one influencer with too many followers is a bad thing – and the bots can become ineffective. There’s a famous social experiment in which actors in a busy New York City street stopped to stare at a window to determine if strangers would do the same. If there are not enough actors staring at the window, strangers are unlikely to respond. But as the number of actors increases, the likeness of a stranger stopping to look will also increase. The bot swarms also have an optimal number of leaders required to have the largest influence on their followers. Perhaps we’re much more like robots than the Turing test would have us believe.

Dot to dot

We’re a long way from intelligent robot swarms, though, as Everardo is using simplified 2D particle simulations to begin to tackle this problem. In this case the particles replace the robots, and are essentially just dots (rodots?) in a shared environment that only has two dimensions. The objectives or points of interest for these dot bots are more dots! Despite these simplifications, translating system feedback into a performance review for the leaders is still a challenging problem to solve computationally. Everardo starts by asking the question “what if the leader had not been there”, but then you have to ask “what if the followers that followed that leader did something else?” and then you’ve opened a can of worms reminiscent of Smash Mouth where the “what if”’s start coming and they don’t stop coming.

What if you wanted to know more about swarming robots? Be sure to listen live on Sunday February 26th at 7PM on 88.7FM, or download the podcast if you missed it. To learn a bit more about Everardo’s work with swarms and all things robotics, check out his portfolio at everardog.github.io.