Alaska is home to four subspecies of gray wolves whose diets differ depending on where in the state they are and the food resources they have access to. While the wolves themselves may be difficult to keep track of, scat (poop) won’t try to run away and contains enough information to help researchers understand the diets of these animals. The Levi Lab, here at OSU, maintains a large library of DNA material collected from Alaskan wolf scat samples. What if this DNA could tell us more about the lives of Alaskan wolves and help us more deeply understand the diseases they are exposed to? This is exactly the question that our guest this week is trying to answer.

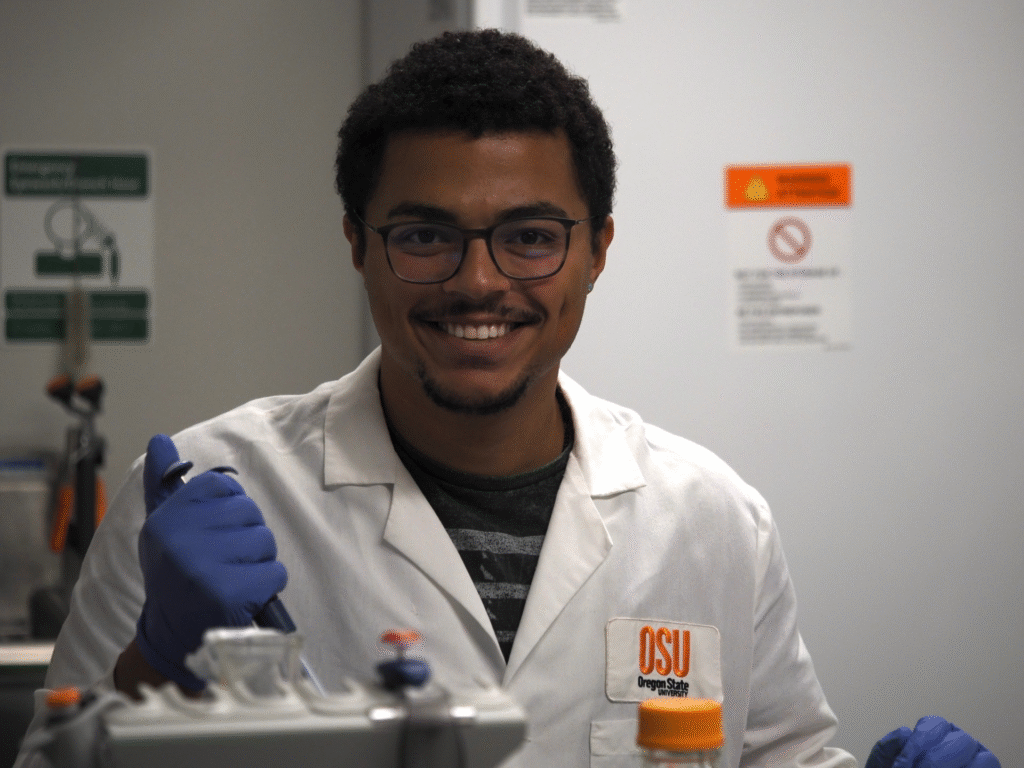

This week on the show, we are joined by Zach Muniz, a 2rd year master’s student under the advisement of Dr. Taal Levi in the Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Sciences. Using Levi Lab materials, resources from collaborators and publicly available databases, Zach is developing methods to study the helminthic parasites that pass through the digestive tracts of Alaskan wolves. Zach extracted helminthic DNA from over 930 wolf scat samples during his time here at OSU! When Zach isn’t in the lab, he enjoys giving back to the community by mentoring the next generation of scientists in science communication programs such as OSU Explore and More, and Salmon Watch.

Tune into KBVR 88.7 FM at 7:00 pm PST on February 8th to hear Zach describe the many stepping stones of his journey to and through graduate school!

Written by Emilee Lance