In February of 2021, the Office of Undergraduate Education launched the Transitions Survey to learn from first-year OSU students and provide insights about the undergraduate student transition experience specific to the Corvallis Campus. The invitation to participate was extended to all first-year students (first-year freshman and first year transfer students) who had matriculated during summer or fall 2020. Of the 4941 students invited, 22.5% answered at least two questions on the survey.

Recently, I had an opportunity to review results from several of the survey’s academic-related questions. While Erin Bird (Transfer Transitions Coordinator) and Megan and Danielle (URSA interns working on this project) are by far the experts on this survey and the analysis, I’d like to reflect on a few of the areas I found intriguing and share ideas for using those insights in our work.

First-year students emphasized academic goals.

I’ve long been curious about goals that first year students identify for themselves. Question 2 of this survey asked respondents, “During your first few terms enrolled at Oregon State, what were you hoping to accomplish? (Please select all that apply).” Of the 16 options provided, the responses selected by the highest percentage of respondents were “Enrolling in the courses I want,” “Earning the grades I want,” and “Learning in my courses.”

I’ve long been curious about goals that first year students identify for themselves. Question 2 of this survey asked respondents, “During your first few terms enrolled at Oregon State, what were you hoping to accomplish? (Please select all that apply).” Of the 16 options provided, the responses selected by the highest percentage of respondents were “Enrolling in the courses I want,” “Earning the grades I want,” and “Learning in my courses.”

I was surprised by the emphasis on academic goals, as I expected some co-curricular and social engagement goals to factor in as highest priorities as well. As a caveat: learning and earning grades are deeply connected to a student’s social network, sense of belonging, mental health, and support systems and these results don’t undermine those connections. I’m excited that these results offer us a chance to frame ongoing orientation experiences (first-year courses, fall term events) around students’ self-identified priorities. If students name learning, grades, and course access as top priorities, we have an entry point to frame resources and information in service to those goals. If we audit our own orientation and transition support, how often do these topics come up? Are they clearly addressed and visible to students?

Information about motivation, time management, academic support, and advising was identified as key to success.

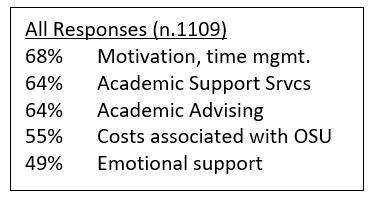

Knowing what kind of help is available and how to access it is, in my opinion, a key component of student success. Question 4 of the survey asks students to identify “which of the following types of information are most important to your success at Oregon State. Please select all that apply.” Motivation and time management was the top response, followed by Academic Support Services and Academic Advising. These responses make sense given students’ earlier responses. Motivation and time management seem directly related to academic goals—particularly for students transitioning from a semester system to a quarter system, and especially during remote learning.

Knowing what kind of help is available and how to access it is, in my opinion, a key component of student success. Question 4 of the survey asks students to identify “which of the following types of information are most important to your success at Oregon State. Please select all that apply.” Motivation and time management was the top response, followed by Academic Support Services and Academic Advising. These responses make sense given students’ earlier responses. Motivation and time management seem directly related to academic goals—particularly for students transitioning from a semester system to a quarter system, and especially during remote learning.

At the Academic Success Center, we often field questions about time management tools, breaking down assignments, scheduling exam prep, and more. Perhaps we can work as a campus to make these topics more visible and integrated within conversations, first year courses, advising, and other transition experiences. Students also indicated that they valued information about Academic Support Services and Academic Advising. To me, this calls for more reflection. What type of information do students need to access services? What information is important for them? What services are available? I believe students’ responses to the resource awareness questions can help us begin to answer these questions.

Increased awareness and more information may expand resource utilization.

Respondents were asked to identify categories of services they had used. Those who selected “yes” to having used Academic Services & Offices were asked what made them want to use the service again. Those who selected “no” they hadn’t used Academic Services & Offices were asked what held them back from using those services. About one third of students who answered this question indicated they “wanted to use it but did not know what to say or how to get started;” a third said they were “intimidated to go by myself;” and 40% said “I did not know how to access the office/service in a remote setting.”

I find these results compelling because I believe they indicate barriers we can address with orientation and way-finding support. Many of us share information about resources, but often this resource exists, and this is its name. These results suggest we could better aid students by clarifying how to access resources, what to expect when they arrive, and how to get started. If we have time and capacity in our conversations, we could more intentionally invite discussion around concerns and barriers, answer questions, and help students develop plans for accessing resources.

Where to next?

I find myself curious to know the degree to which these trends were unique to the remote delivery of classes in fall and winter or if we will see similar patterns when classes are in-person. Lucky for us, Erin will be running this survey each year, and we’ll have more context for how students’ transition to OSU was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and which trends and patterns are more enduring.

If you have additional questions or are interested in more of the findings from the Transition Survey, I encourage you to reach out to Erin Bird (Erin.Bird@oregonstate.ed). The email invitation as well as the questions from the survey itself are available at this link: https://beav.es/Jb7 (Box login required).