In April 2020, a small team of folks from Student Affairs and Academic Affairs designed and administered a survey to undergraduate, Corvallis-campus based students to better understand the student experience during the transition to remote learning. Since then, this team has conducted four additional surveys to gain insights into students’ experiences and perspectives.

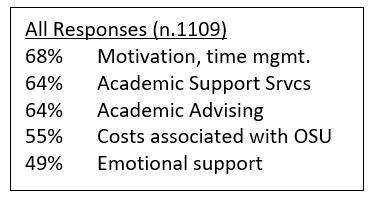

In late October 2022, we initiated the fifth survey in this series and received responses from 2600 students. We will be releasing the full findings within the next few weeks, but I wanted to pull out a few key points that piqued my curiosity on the broader question: “What should communication look like between students and OSU?” Fortunately for all involved, I’m not the one answering this question. In fact, the Constituent Relationship Management (CRM) team is engaging in that work right now, and that group will review the responses on a few questions they helped design. For the scope of this blog, I want to highlight some areas of curiosity that came up relative to that theme of communicating with students:

- I coded the question “What support do you think you most need so you can be successful this year at OSU?” – the top two themes were financial support and academic resources, but many students used that space to give feedback on a specific course or instructor. The survey isn’t designed for local feedback of that sort, so I interpret this to mean we have a gap in our communication structure. How do we empower students to talk to their instructors? And, when needed (although rare), what mechanisms are in place for students when genuine issues with an instructor arise? I am intrigued by the feedback form the College of Science has in place and wonder what the role this form or others like it might play in supporting interaction between students and instructors.

- Near the end of the survey we asked “What do you wish we would have asked about in this survey?” Erin Bird coded these responses, and I saw in those themes an opportunity to do more to hear from students. They asked that OSU ask more about their experience as a student, ask questions about their mental health, and check in on them more. We don’t need to survey students more to create spaces for them to feel heard and to convey that they matter to the university. What opportunities already exist for students to share about their experience, or for an instructor, advisor, or support personnel to indicate interest in how they’re doing? What would that look like?

- At the end of the survey, we asked students to leave their name and email address if they’d like to receive follow-up information and resources. Getting email outreach after finishing a survey isn’t an ideal way to connect, and yet 33% of our respondents were interested in additional communication at the end of the survey. There is a clear interest for students in timely information about resources. I am curious where the appropriate home might be for an “I want outreach/help/information” request within our university ecosystem.

- The overall survey response rate was low (under 20%)—lower, in fact, than the other surveys in the series. On the other hand, the students who completed the survey gave rich and robust responses. When asked to define success, over 2100 respondents offered up 35,000 words. With both of those data points in mind, I am curious: how can we create routine mechanisms for students to share feedback that will be reviewed and shared more broadly?

I may have just offered four reasons not to administer a large-scale survey, but I actually believe wholly in this effort (and want to increase the response rate). But a survey alone can’t accomplish our communication needs, and I believe that students and administrators, faculty, and staff would benefit from more nuanced conversation. For students, the value is in learning about resources in a timely fashion, an ability to give input and share their experience, and, at times, be checked-in on. From OSU’s perspective, having student input and perspective is vital in key success initiatives, effective communication, and our overall understanding of what needs and concerns exist.

We can and are working on large-scale communication through the CRM project and survey efforts like this, but I don’t want to lose sight of the ways we can do the work of communication at the small scale too. Individual people – student support personnel, advisors, instructors can play an important role here through day-to-day conversations with students. This week I’m going to pay attention to the conversations I’m having, and identify places where checking-in, inviting perspective, and offering resources can show up within existing dialogues.

For those interested in the full results of the survey, Erin Bird, Maureen Cochran, and I will be presenting as part of the FYI Friday series on Friday, February 3rd, at 1:00 pm via Zoom. Registration is required. If you are unable to attend, a recording will be available in Box along with the final report.