NDAs and Open Pedagogy

One of the principles upheld by the open pedagogy movement is that the role of the learner must be active and the tasks that they engage in must be meaningful. These are not new ideas by any stretch, but as we move toward a more open pedagogical environment, it becomes necessary to examine the types of assignments that we create and assign. How do these tasks contribute to efforts to democratize education and increase learner autonomy, engagement, and freedom? What makes an assignment open? To answer these questions, this post will explore the relationship between open pedagogy and open assignments.

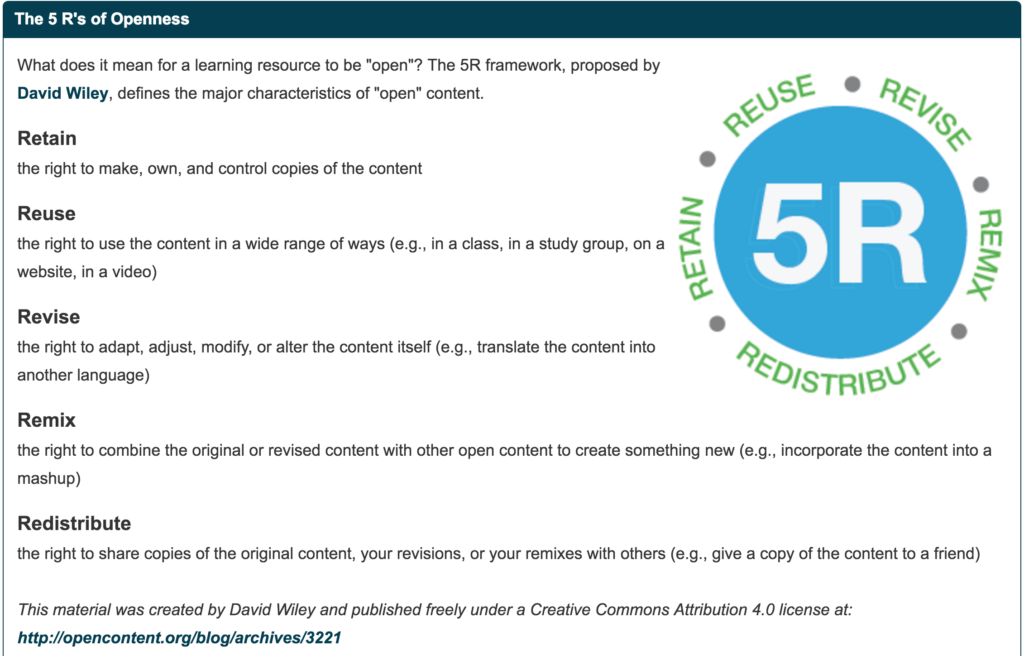

While interest in the topic of open pedagogy has steadily gained steam in the roughly 50 years since its inception, definitions of and familiarity with the concept of today’s open pedagogy vary among educational practitioners. Some discussions focus on the expansion of the use of these resources. You might be hard-pressed to find an instructor who hasn’t at least reused open content (See 5R framework of Open Content) or encountered such materials as a student. Other conversations emphasize the remix and revise aspect of open content and pedagogical practices, and the number of faculty-created Open Educational Resources (OERs) intended to replace the traditional textbook is ever increasing. Still others have turned their attention to implementation of open pedagogical practices that put students in the role of content creators rather than passive beneficiaries of innovations in open content. In our efforts to create tasks that accomplish this shift in the role of the learner, we must first ask what the value of the task is for the student, peers, and the larger community, and what life will such a task have after its completion. To answer these questions, we can look to the non-disposable assignment (NDA).

Non-Disposable Assignments (NDAs)

To define the characteristics of this type of assignment, it is helpful to first define what we mean by “disposable” assignment. It is safe to say that we are all familiar with these types of assignments: typically they include one-off or busy work tasks designed to be filed away and forgotten as soon as completed and graded. In his article What is Open Pedagogy (2013), David Wiley described the disposable assignment in this way:

These are assignments that students complain about doing and faculty complain about grading. They’re assignments that add no value to the world – after a student spends three hours creating it, a teacher spends 30 minutes grading it, and then the student throws it away. Not only do these assignments add no value to the world, they actually suck value out of the world.

Online learning within the confines of a learning management system (LMS) is particularly ripe for these types of assignments. In fact, one could argue they are designed for this type of task. In an online course, instructors create and post the assignment, students complete it, instructors grade it, the course ends, student work is deleted, the course is rolled over, and the next crop of students begins the cycle again. The work is designed to be contained within the LMS for the duration of a course, not to be shared with a broader audience of students or colleagues.

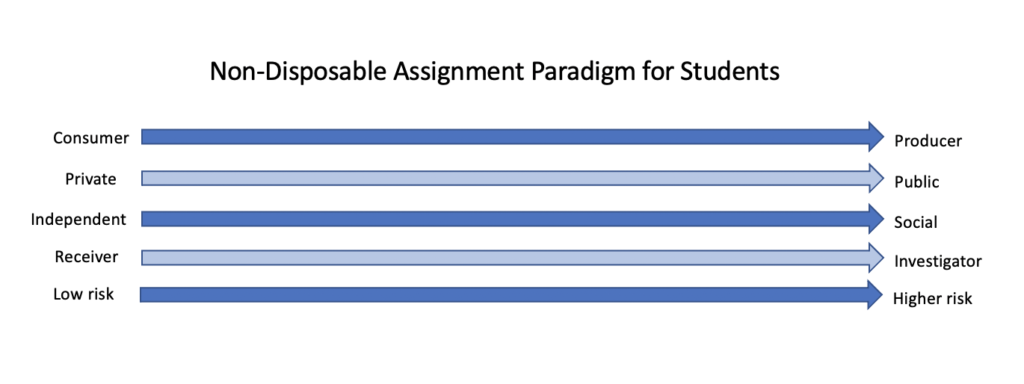

As an alternative to the disposable assignment in favor of more meaningful tasks, Wiley coined the term Non-Disposable Assignment. The NDA (also referred to as a renewable assignment), in contrast to its binworthy counterpart, is an assignment that “adds value to the world.” Later definitions, no doubt influenced by the growing open pedagogy movement and the promotion of the use of OER materials, go further and hold that an NDA ought to produce a resource that is openly published so that “others can find, use, and if desired, repurpose or update the work,” (Jhangiani, 2015; Wiley, 2013; Wiley et al., 2017; Wiley & Hilton, 2018). Such assignments put the learner in the role of creator and impact or benefit an audience beyond the instructor and student. Because the premise of the NDA is that it can not only be shared widely, but also revised and reused without permission by both instructors and students, the content should be openly licensed. Considering the role of learners as authors of the content, they should have a say in determining the type of open license appropriate for their work.

In the article A Conceptual Framework for Non-Disposable Assignments: Inspiring Implementation, Innovation, and Research, Seraphine et al (2019) provide a set of principles NDAs must adhere to. The Five Principles are summarized as follows:

- NDAs fundamentally involve information collaboration and exchange.

- As forms of responsive and responsible pedagogy, NDAs involve communication throughout and opportunities for revision, creativity, modifying key terms and objectives, etc.

- While NDAs might not necessarily involve communal assembly, the resulting product or practice must always be shared outside the teacher-student dyad, creating opportunities for communal access of the NDA as an information resource

- NDAs produce learning through cooperative critique.

- Because they are not exams or isolated writing assignments, NDAs involve innovation as a fundamental concept.

Benefits and Value of NDAs

Apart from their ability to reach a broad audience, NDAs increase student motivation, engagement and autonomy resulting in improved achievement of learning outcomes. (Ariely, Kamenica, & Prelec, 2008; Chalofsky & Krishna, 2009; Pink, 2011). While this claim may be at least in part anecdotal, it follows that when students know that their work may be used by peers, faculty, and colleagues across their field in the future, investment in the quality of their work increases. Non-disposable assignments and authentic assessments have the potential to add value in other areas by:

- promoting community engagement.

- fostering innovation.

- interrogating and dismantling systems of oppression by centering experiences of historically marginalized groups.

- providing opportunities for culturally rich content (inject identity, student influence over content).

- cultivating information literacy skills.

- increasing accessibility to educational resources.

- helping students communicate in writing to a general audience.

- offering opportunities to collaborate with peers around the world.

- increasing self-regulated learning and autonomy.

Despite their numerous benefits, NDAs are not without challenges and risks. For example, some students may be resistant to the exposure and the vulnerability inherent in creating open content for broad use. In such cases, instructors must provide alternative assignments or options not to share. Because student-generated content requires substantial metacognitive skills, instructors must ensure that NDAs involve significant scaffolding at multiples stages in the learning process (Zimmerman, 1990; Zimmerman, 2002). Furthermore, the open nature of student-generated content presents a quality control challenge that instructors must anticipate and address by providing multiple opportunities for revision and peer review.

NDA Design and Students as Producers

Implementing assignments that have the potential for broad impact beyond the typical instructor-student dyad can seem daunting. After all, conceptualizing and creating tasks that effectively revise the role of student from a passive one to actual content creators is no small feat. However, it is important to remember that the scope can vary widely. Indeed a well-crafted discussion between two students might form the basis for a renewable assignment. Other examples may include experiential connections such as student-generated podcasts; the production of flyers, guidelines, or materials for local community organizations; or even collaboratively created and maintained global resources such as wikis like the Chemistry Library. Whatever the scope, NDAs can—and arguably should—be iterative allowing for innovation and adaptation to various contexts.

With the role of the student as producer in mind and an understanding of the potential pitfalls that an open assignment might present, faculty can then turn to the conventional principles of backward design to develop meaningful student learning experiences that add value for learners and their peers while also promoting community engagement.

Examples & Resources

- Chemistry Library

- Examples from various fields

- Human Anatomy (Student created OER)

- Libretexts

- Methods of Education Technology: Principles, Practice, and Tools

- Open Anthology of American Literature

- Open Oregon Educational Resources

References

- Jhangiani, R. (2017). Ditching the ‘‘disposable assignment’’ in favor of open pedagogy. http://teachpsych.org/E-xcellence-in-Teaching-Blog/4583103.

- Paskevicius, Micheal, Knaack, Liesel (2017). The Non-Disposable Assignment: Enhancing Personalised Learning – Session 1 (Slideshare) https://www.slideshare.net/mpaskevi/the-nondisposable-assignment-enhancing-p

- Seraphin SB, Grizzell JA, Kerr-German A, Perkins MA, Grzanka PR, Hardin EE. A Conceptual Framework for Non-Disposable Assignments: Inspiring

- Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is Open Pedagogy? Retrieved 15 June 2022, from https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/297

- Zimmerman, B. J. , Becoming a self-regulated learner. Theory into Practice, 2002; 41, 65-70. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2.