I have always struggled with test anxiety. As a student, from first-grade spelling tests through timed essay questions while earning my Masters of Science in Education, I started exams feeling nauseous and underprepared. (My MSEd GPA was 4.0). I blame my parents. Both were college professors and had high expectations for my academic performance. I am in my 50s, and I still shutter remembering bringing home a low B on a history test in eighth grade. My father looked disappointed and told me, “Debbie, I only expect you to do the best you can do. But I do not think this is the best you can do.”

I am very glad my parents instilled in me a high value of education and a strong work ethic. This guidance heavily influenced my own desire to work in Higher Ed. Reflecting on my own journey and the lingering test anxiety that continues to haunt me, it has become evident that equipping students with comprehensive information to prepare for and navigate quizzes or exams holds the potential to alleviate the anxiety I once struggled with.

Overlooking the instructions section for an exam, assignment, or quiz is common among instructors during online course development. This might seem inconsequential, but it can significantly impact students’ performance and overall learning experience. Crafting comprehensive quiz instructions can transform your course delivery, fostering a more supportive and successful student learning environment.

The Role of Quizzes in Your Course

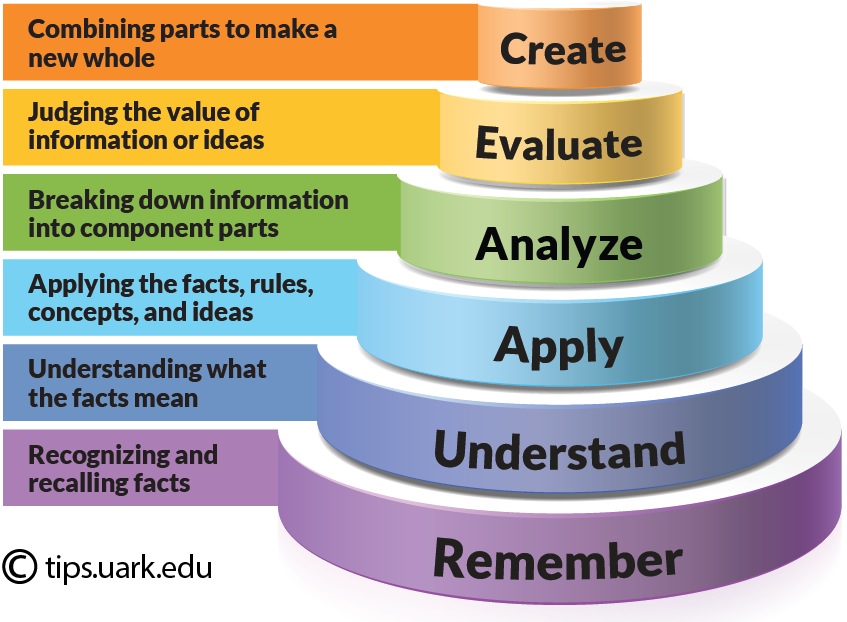

Quizzes serve as diagnostic and evaluative tools. They assess students’ comprehension and application of course materials, helping identify knowledge gaps and areas for additional study. The feedback instructors receive through student quiz scores enables instructors to evaluate the effectiveness of the course learning materials and activities and understand how well students are mastering the skills necessary to achieve the course learning outcomes. This enables instructors to identify aspects of the course design needing improvement and modify and adjust their teaching strategies and course content accordingly. By writing thorough and clear quiz instructions, you support students’ academic growth and improve the overall quality of your course.

Explain the Reason

Explain how the quiz will help students master specific skills to motivate them to study. The skills and knowledge students are expected to develop should be clearly defined and communicated. Connect it to course learning outcomes and encourage students to track their progress against them (Align Assessments, Objectives, Instructional Strategies – Eberly Center – Carnegie Mellon University, n.d.).

Why did you assign the quiz? Would you like your students to receive frequent feedback, engage with learning materials, prepare for high-stakes exams, or improve their study habits?

Equipping Students for Successful Quiz Preparation

Preparing for a quiz can be daunting for students. To help them navigate this process, provide a structured guide for preparation. Leading up to the quiz, you may want to encourage your students to:

- Review the lectures: Highlight the importance of understanding key concepts discussed.

- Review the readings: Encourage students to reinforce their understanding by revisiting assigned readings and additional materials.

- Engage in review activities: Suggest using review materials, practice questions, or study guides to cement knowledge.

- Participate in discussions: Reflecting on class discussions can offer unique insights and deepen understanding.

- Seek clarification: Remind students to contact their instructor or teaching assistant for any questions or clarifications. You add a Q&A discussion forum for students to post questions leading up to the quiz.

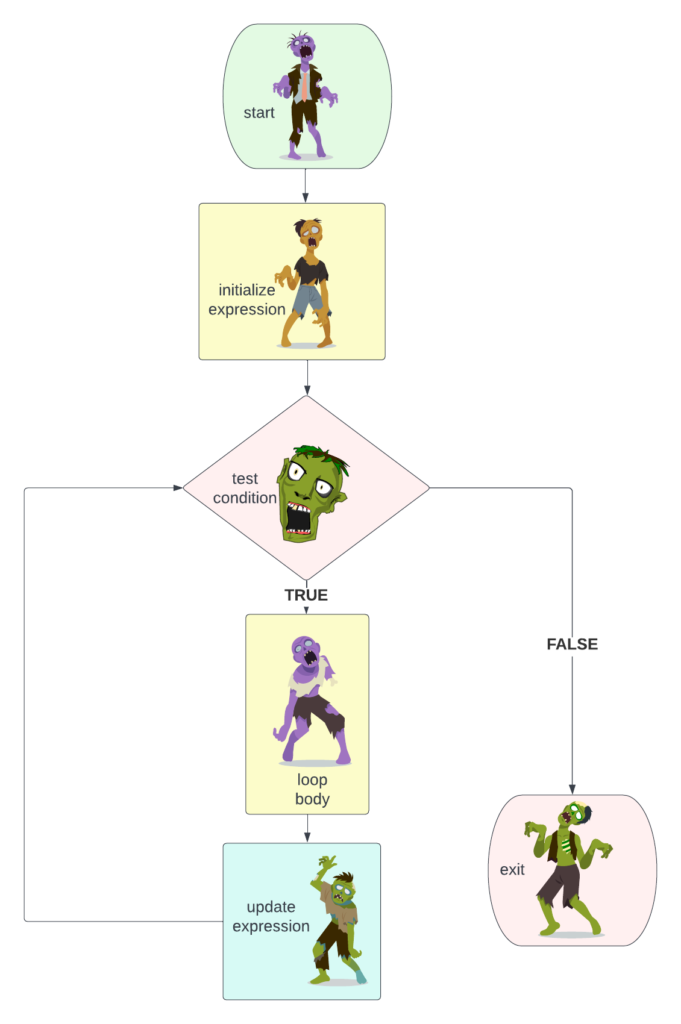

Crafting Clear and Detailed Quiz Instructions

When taking the quiz, clear instructions are vital to ensure students understand what is expected of them. Here’s a checklist of details to include in your quiz instructions:

- Time Limit: Explicitly mention the duration of the quiz, the amount of time students have to complete the quiz once they have started it, or if it’s untimed. Suggest how they may want to pace the quiz to ensure they have time to complete all the questions.

- Availability Window: You should specify an availability window for asynchronous online students. It refers to the time frame during which the quiz can be accessed and started. By giving an extended window, you allow students to take the quiz at a time that suits them. Once they begin, the quiz duration will apply.

- Number of Attempts: Indicate whether students have multiple attempts or just a single opportunity to take the quiz.

- Question Format: Provide information about the types of questions included and any specific formatting requirements.

- Quiz Navigation: Have you enforced navigational restrictions on the quiz, such as preventing students from returning to a question or only showing questions one at a time? Share this information in the instructions and explain the reasoning.

- Point Allocation: Break down how points are distributed, including details for varying point values and partial credit.

- Resources: Specify whether students can use external resources, textbooks, or notes during the quiz.

- Academic Integrity Reminders: Reinforce the importance of academic integrity, detailing expectations for honest conduct during the quiz.

- Feedback and Grading: Clarify how and when students will receive feedback and their grades.

- Showing Work: If relevant, provide clear guidelines on how students present their work (solving equations, pre-writing activities, etc.) or reasoning for particular question types.

End with a supportive “Good Luck!” to ease students’ nerves and inspire confidence.

Crafting comprehensive quiz instructions is a vital step in ensuring successful course delivery. Providing students with clear expectations, guidelines, and support enhances their quiz experience and contributes to a positive and productive learning environment (Detterman & Andrist, 1990). As course developers and designers, we are responsible for fostering these optimal conditions for student success. Plus, as my father would say, it is satisfying to know you have “done the best you can do.”

References

Footnote: My son called as I was wrapping up this post. I told him I was finishing up a blog post for Ecampus. “I kind of threw Grandpa under the bus,” I said. After I shared the history test example, he said, “you didn’t learn much.” He and his sister felt similar academic pressure; I may have even used the same line about the best you can do. In my defense, he is now. Ph.D. candidate in Medicinal Chemistry and his sister just completed a Masters in Marine Bio.