By Greta Underhill

In my last post, I outlined my search for a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) program that would fit our Research Unit’s needs. We needed a program that would enable our team to collaborate across operating systems, easily adding in new team members as needed, while providing a user-friendly experience without a high learning curve. We also needed something that would adhere to our institution’s IRB requirements for data security and preferred a program that didn’t require a subscription. However, the programs I examined were either subscription-based, too cumbersome, or did not meet our institution’s IRB requirements for data security. It seemed that there just wasn’t a program out there to suit our team’s needs.

However, after weeks of continued searching, I found a YouTube video entitled “Coding Text Using Microsoft Word” (Harold Peach, 2014). At first, I assumed this would show me how to use Word comments to highlight certain text in a transcript, which is a handy function, but what about collating those codes into a table or Excel file? What about tracking which member of the team codes certain text? I assumed this would be an explanation of manual coding using Word, which works fine for some projects, but not for our team.

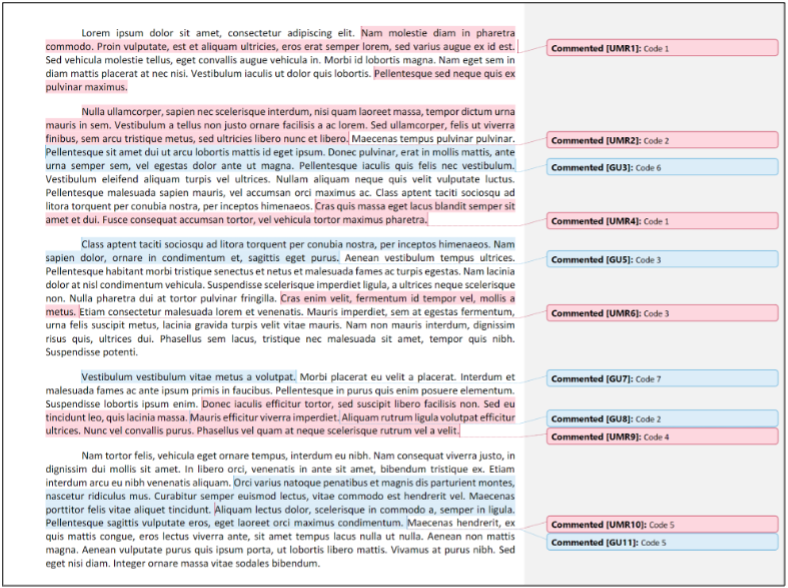

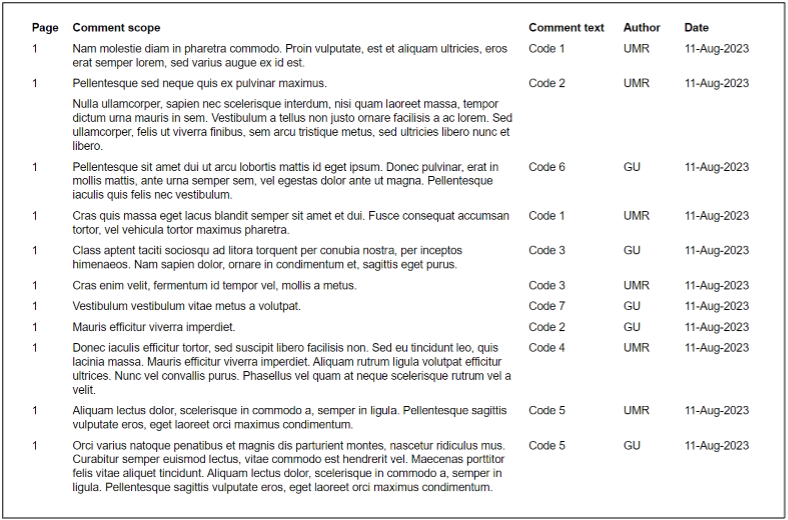

Fortunately, my assumption was wrong. Dr. Harold Peach, Associate Professor of Education at Georgetown College, had developed a Word Macro to identify and pull all comments from the word document into a table (Peach, n.d.). A macro is “a series of commands and instructions that you group together as a single command to accomplish a task automatically” (Create or Run a Macro – Microsoft Support, n.d.). Once downloaded, the “Extract Comments to New Document” macro opens a template and produces a table of the coded information as shown in the image below. The macro identifies the following properties:

- Page: the page on which the text can be found

- Comment scope: the text that was coded

- Comment text: the text contained in the comment; for the purpose of our projects, the code title

- Author: which member of the team coded the information

- Date: the date on which the text was coded

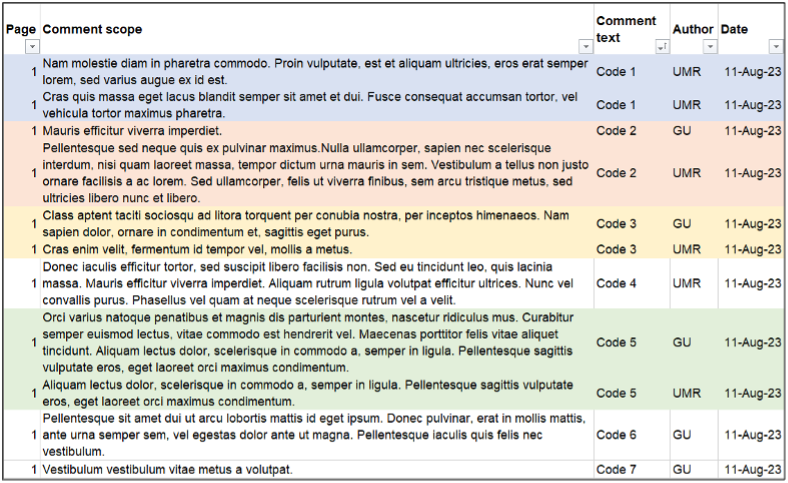

You can move the data from the Word table into an Excel sheet where you can sort codes for patterns or frequencies, a function that our team was looking for in a program as shown below:

This Word Macro was a good fit for our team for many reasons. First, our members could create comments on a Word document, regardless of their operating system. Second, we could continue to house our data on our institution’s servers, ensuring our projects meet strict IRB data security measures. Third, the Word macro allowed for basic coding features (coding multiple passages multiple times, highlighting coded text, etc.) and had a very low learning curve: teaching someone how to use Word Comments. Lastly, our institution provides access to the complete Microsoft Suite so all team members including students that would be working on projects already had access to the Word program. We contacted our IT department to have them verify that the macro was safe and for help downloading the macro.

Testing the Word Macro

Once installed, I tested out the macro with our undergraduate research assistant on a qualitative project and found it to be intuitive and helpful. We coded independently and met multiple times to discuss our work. Eventually we ran the macro, pulled all comments from our data, and moved the macro tables into Excel where we manually merged our work. Through this process, we found some potential drawbacks that could impact certain teams.

First, researchers can view all previous comments made which might impact how teammates code or how second-cycle coding is performed; other programs let you hide previous codes so researcher can come at the text fresh.

Second, coding across paragraphs can create issues with the resulting table; cells merge in ways that make it difficult to sort and filter if moved to Excel, but a quick cleaning of the data took care of this issue.

Lastly, we manually merged our work, negotiating codes and content, as our codes were inductively generated; researchers working on deductive projects may bypass this negotiation and find the process of merging much faster.

Despite these potential drawbacks, we found this macro sufficient for our project as it was free to use, easy to learn, and a helpful way to organize our data. The following table summarizes the pro and cons of this macro.

Pros and Cons of the “Extract Comments to New Document” Word Macro

Pros

- Easy to learn and use: simply providing comments in a Word document and running the macro

- Program tracks team member codes which can be helpful in discussions of analysis

- Team members can code separately by generating separate Word documents, then merge the documents to consensus code

- Copying Word table to Excel provides a more nuanced look at the data

- Program works across operating systems

- Members can house their data in existing structures, not on cloud infrastructures

- Macro is free to download

Cons

- Previous comments are visible through the coding process which might impact other members’ coding or second round coding

- Coding across paragraph breaks creates cell breaks in the resulting table that can make it hard to sort

- Team members must manually merge their codes and negotiate code labels, overlapping data, etc.

Scientific work can be enhanced and advanced by the right tools; however, it can be difficult to distinguish which computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software program is right for a team or a project. Any of the programs mentioned in this paper would be good options for individuals who do not need to collaborate or for those who are working with publicly available data that require different data security protocols. However, the Word macro highlighted here is a great option for many research teams. In all, although there are many powerful computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software programs out there, our team found the simplest option was the best option for our projects and our needs.

References

Create or run a macro—Microsoft Support. (n.d.). Retrieved July 17, 2023, from https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/create-or-run-a-macro-c6b99036-905c-49a6-818a-dfb98b7c3c9c

Harold Peach (Director). (2014, June 30). Coding text using Microsoft Word. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TbjfpEe4j5Y

Peach, H. (n.d.). Extract comments to new document – Word macros and tips – Work smarter and save time in Word. Retrieved July 17, 2023, from https://www.thedoctools.com/word-macros-tips/word-macros/extract-comments-to-new-document/