Have you implemented office hours in your online course, with few students taking advantage of that time to connect? This can often seem like a mystery, when we hear so often from Ecampus students that they desire to build deeper relationships with their instructors. Let’s dive into some of the reasons why online students may be hesitant to attend and identify a few ways we can improve this in our courses.

Who are our learners?

To help us address this question, let’s first consider who our learners are. The vast majority of Ecampus students are working adults who complete coursework in the evenings and on weekends, outside of regular business hours.

Ecampus learners reside in all 50 states and more than 60 countries. The people who enroll in Ecampus courses and programs consist of distance (off-campus) students — whose life situations make it difficult for them to attend courses on Oregon State’s Corvallis or Bend campuses — and campus-based students who may take an occasional online course due to a schedule conflict or preference for online learning. Here is a student demographic breakdown for the 2021-22 academic year: Approximately 26% of OSU distance students live in Oregon. The average age of OSU distance students is 31.

Data shared from Ecampus News

Considering this data about our online population, along with qualitative survey data and insights from our student success team, we can also deduce some additional factors. Our students are:

- Working professionals, balancing family and personal commitments

- Concerned about time

- Often feel stressed and overwhelmed

- Seeking flexibility and understanding

- Located in a variety of time zones, with mixed schedules

- From a number of cultural backgrounds and perspectives

- Looking to identify the value of tasks/assignments and seeking how their education will benefit them personally

- May experience self-doubt, imposter syndrome, or hesitancy around their ability to successfully complete their program

Identifying the barriers

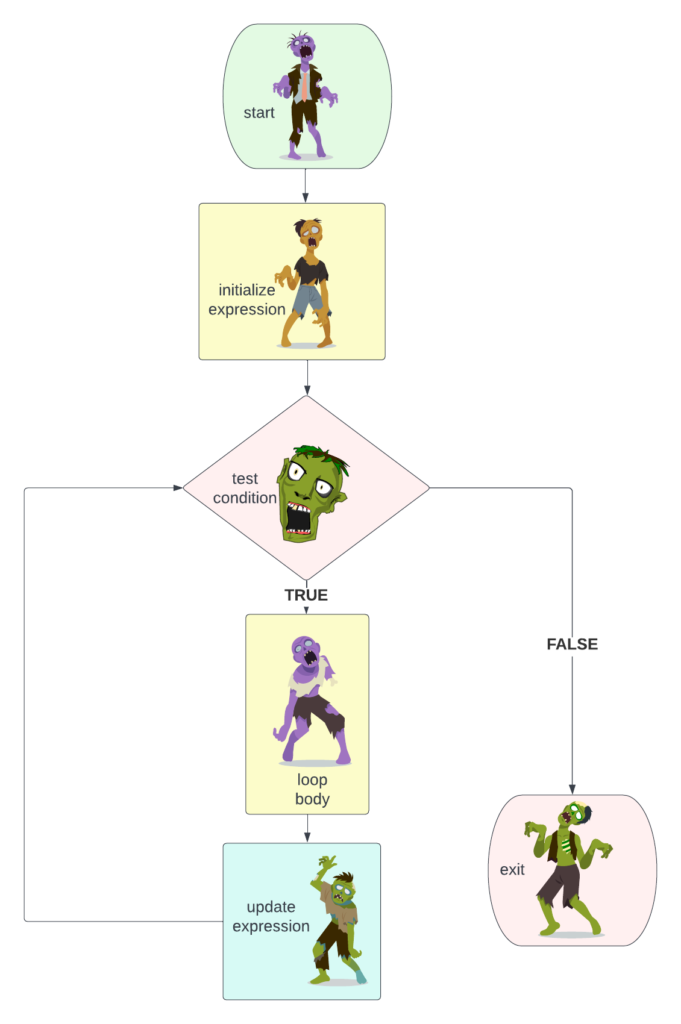

Now that we have a better understanding of our online learners and some of the challenges they face, let’s consider how they approach office hours. The slide below, shared at a TOPS faculty workshop in 2020, outlines some of the self-reported reasons that students may not be engaging in support sessions or reaching out for help.

Students may have the connotation that office hours are for ‘certain types of concerns’ and not see it as a time to connect with their instructor on other areas of interest (i.e. graduate school, career planning, letters of recommendation, etc.) They may also see it as a sign of weakness or fault, rather than a strength for being able to utilize that time to build a relationship or increase their learning. Students may have also had past experiences, at OSU or elsewhere, that have formed an understanding of what office hours entail and what is allowed at these meetings.

Student feedback

In the Ecampus Annual Survey (2020), when asked about faculty behavior that made them feel comfortable attending office hours, students shared that instructor friendliness, promptly answering student questions, providing accessible and flexible office hour options, and demonstrating strong communication throughout the course were specifically helpful in encouraging use of office hours. (Ecampus Annual Student Survey)

Those who had not taken advantage of office hours shared reasons that generally fell into four categories:

- Office hours conflicted with life and were not accessible to them

- The student had not yet needed to use office hours

- Using other forms of communication to ask for help

- Lack of awareness of if or when office hours were offered

Alternative approaches

Rename and reframe ‘office hours’

To help students identify the purpose of your Office Hours time, and to make it a little less intimidating, you might consider renaming these hours. Some ideas include Student Hours, Homework Help, Ask Me Anything Hours, Virtual Coffee Chat, etc. Some instructors separate times for course related questions from times that are more for connection and talking about outside topics such as current industry news, future planning, etc.

It’s important to be clear with students what they can discuss with you at these times, and to also encourage their participation and welcome it. You could do this by choosing intentional wording in the way you share your hours, and also sending reminders by announcement or direct message.

Offer flexibility

To help make your hours accessible to a variety of students, you might consider offering a number of different times throughout the term, staggering when those are available (i.e. morning, lunch, evening, or a weekend day). You can also offer the option to request office hours by appointment.

Another strategy would be to survey your students at the beginning of the term to see when the best times are for the majority of the class. You could also leverage this survey to ask about topics of interest or to see if they have any concerns or questions starting off the term.

Consider the tools

For synchronous virtual meetings, we would recommend using Zoom as most OSU students are comfortable with this tool, and everyone has free access to it. Zoom links can be shared, and also integrated into your Canvas course using the tool in the Canvas menu. For asynchronous questions, you might create a Q&A forum for each week or module of the course (and subscribe to ensure timely notification). If you are using Canvas messaging, we recommend outlining that in your communication plan so that students know the best way to reach you.

Some instructors have also experimented with outside tools, such as Gather. Gather is a platform for building digital spaces for teams to connect at a distance. It is free to use for spaces that allow up to 25 users at once. You can chat, enable your mic and camera for audio/video interactions, and create specific areas for small group conversations.

Demonstrate care and community

One of the best strategies for encouraging students to utilize your meeting hours or to reach out for help in other ways, is to demonstrate care throughout your course. This can be done by using welcome and inclusive language in your Syllabus and written course content, having a warm and friendly tone in your media (i.e. recorded lectures and videos), and reaching out proactively to students who may be low in participation or struggling academically.

Resources

- Office Hours for Online Courses – This guide was created by our Ecampus Faculty Support team, and provides a great overview for best practices and implementation.

- Office Hours Explainer – This PDF was designed by OSU’s Academic Success Center, as a student-facing resource on Office Hours. It explains the variety of topics available, steps to take, and preparation for the student. There is a specific section about online courses, but the majority of the guide is applicable to Ecampus students.

- Effective Office Hours – This faculty guide, created by the Center for Academic Innovation at the University of Michigan, offers some ideas for how to leverage virtual office hours, including specific strategies from an instructional perspective.