Over the last couple of terms, I joined a series of reading sessions with instructional design colleagues to read Alfie Khon and Susan Blum’s book Ungrading. Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead) and discuss the practices and implications of this approach to reconceptualize assessment design and the place of grading. This two-part blog aims to capture the takeaways from those discussions including the main concepts, approaches, types of activities, implications, and challenges of adopting ungrading practices. This first part of the blog covers a brief overview of the concept of ungrading, its major benefits, and design considerations; and the second blog will include a summary of the types of ungrading practices and challenges to implementation ––all derived from the authors’ extensive arguments and examples. For a detailed review and summary of the book chapters, you can also check the blog Assessment Design: Ideas from Ungrading Book.

Overview of Ungrading

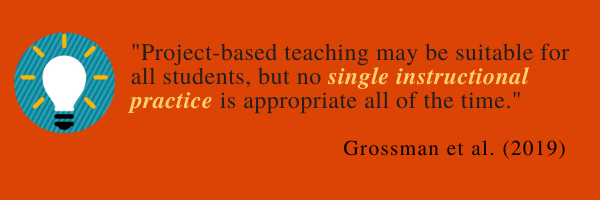

The concept of ungrading is sparking widespread interest only recently even though educators have been studying and using ungrading approaches for quite some time. The foundational premise of ungrading is to move away from a focus on grades that judge, rank, sort, and quantify student learning to adopting an approach that focuses on using alternative and authentic means to assess learning such as self-evaluation, reflection, student-generated questions, peer feedback, to name a few. Along with that premise is the questionable ranking that comes with grading which makes students compete with one another in an artificial way. Sorensen-Unruh (chapter 9) sees ungrading as a conversational method that facilitates the communication between instructors and students about how students perform in the class. If, as underscored by the authors, grading and the fact of assigning point values to students’ performance makes more harm than good, then, why use grading? Considering that grading is rooted in our educational systems, many of these authors conclude that it becomes inevitable to grade student learning as it is currently done today.

Several scholars and instructors consider grading to be problematic. First, grades are not good indicators of learning. Blum (chapter 3) argues that grading assumes all students are the same, does not provide accurate information about student learning gains, is consequential, adds fear and avoidance of negative consequences, and is arbitrary and instructor-led. Second, the overemphasis on grades can lead to a decrease in intrinsic motivation, students’ excessive anxiety, and the complexity of quantifying how learning happens (Stommel, chapter 1). Third, it can also decrease interest in learning, students may feel inclined for easier tasks, and critical thinking is lacking (Alfie Khon, foreword). Fourth, grading makes students be fixated more on their grades than on the process of learning, leading them to believe that grades are all that matters in school (Khon & Blum; Talbert, 2020). And finally, too much focus on grades can be detrimental to students’ mental health (Eyler, 2022). However, ungrading does not mean dismissing grades altogether. Instead, Stommel proposes creating a learning space that fosters critical thinking, reflection, and metacognition– all skills that are valuable for 21st-century education. Likewise, Alfie Khon contends that grading can be participatory since it does not require a unilateral decision, and thus, students can also propose their own grades (with the instructor’s reservation to accept them).

“Ultimately ungrading— eliminating the control-based function of grades, with all its attendant harms— means that, as long as the noxious institutional requirement to submit a final grade remains in place, whatever grade each student decides on is the grade we turn in, period.”

(Khon, 2020, p. xv)

While ungrading may be an innovative approach to assessments, it should be thought of carefully and adopted with a clear objective. Ungrading, as pointed out by Katopodis and Davison (chapter 7), needs a structure to be effective, allowing students to envision themselves as authoritative, creative, confident, and active, thus achieving a high impactful goal. As ungrading requires instructors to evolve in their approach to assessment, it does too for students who are expected to engage in a process of self-evaluation, self-assessment, and reflection. This requires engagement in metacognitive practices that many students might not be ready to embark on or don’t know how to do it. In addition, while ungrading is believed to be student-centered, it can deepen equity gaps if guideposts are entirely removed. Sorensen-Unruh (chapter 9) believes that ungrading is a matter of social justice –going beyond the expected student agency and aiming at having students exercise their voice and participate in assessment decisions.

As a whole, Blum (introduction chapter) provokes us all to rethink the nature of grading considering that students’ learning conditions vary, with many enduring inequities at many levels. Blum wants us to keep focused on how “varying assessment and feedback methods contribute to the real learning of real individual learners, rather than imposing an arbitrary method of sorting.” (p. xxii); all for the sake of healthy learning.

These are a few key points about the arguments for ungrading. While this assessment practice is taking force in higher education, there are also many critics and skeptics. The purpose of this blog is not to enter into the discussion and controversy of ungrading, but to share a few perspectives and takeaways after an intense and well-structured book club discussion. In the following section of this part-one blog, I will share considerations for designing for ungrading.

Assessment Design Considerations

The educational system requires all instructors to submit grades at the end of every term. There is dissatisfaction with the current grading practices among many instructors and students as explained at large in the book. Here is where the ungrading movement takes force to provide alternative ways to account for evidence of student learning. Riesbeck (chapter 8) argued that by implementing ungrading practices, students can focus more on the content and feedback than on the grades. The use of critique-driven learning allows for more easily quantifiable efforts, progress, and accomplishment. Each ungrading consideration is dependent on a myriad of factors that may or not apply to each instructor’s context. The bottom line in ungrading is re-envisioning the teaching and learning process, engaging students in active learning, and active self-assessment through feedback. The following are design considerations:

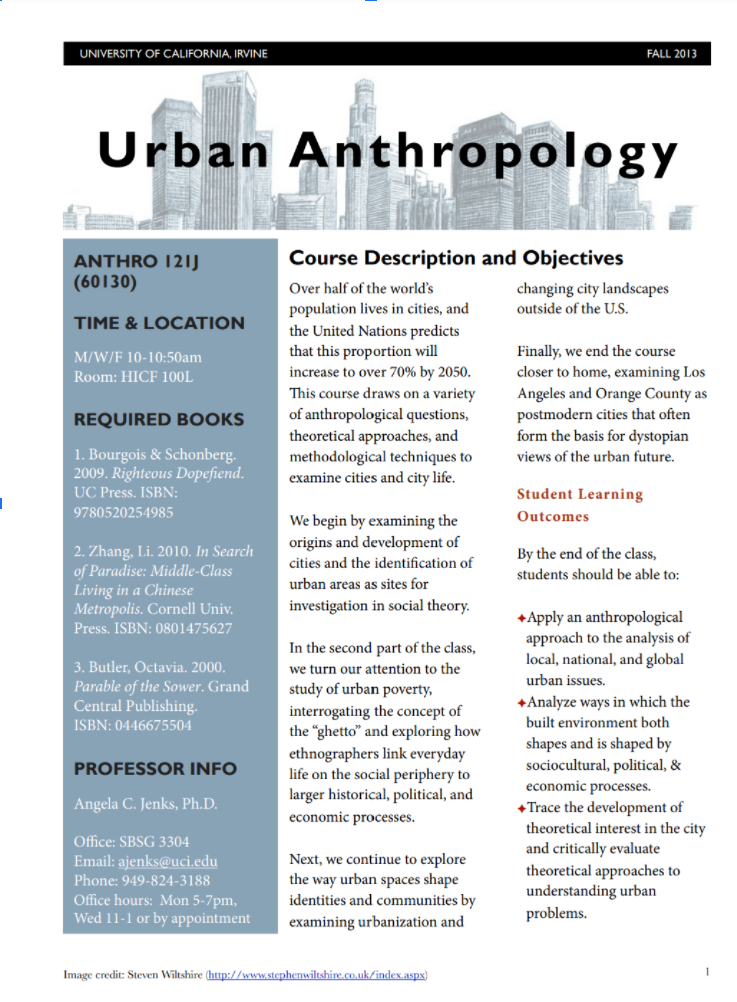

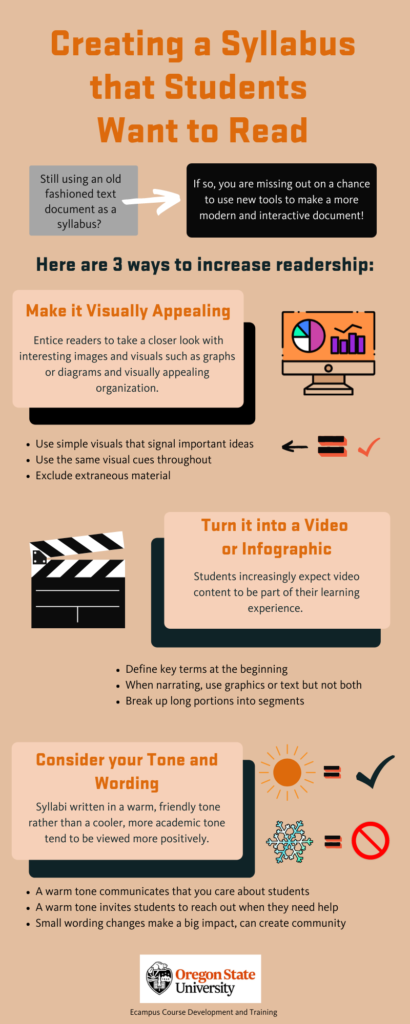

Decenter grading and communicate (un)grading practices

Instructors can encourage students to focus on the process of learning, instead of talking about grades, Blums says, we should talk about the purpose and goals of the activities with students. These conversations can help develop relationships with students to encourage them to own their learning and have a voice in that process. Decentering grades also involves having an ongoing conversation with students, colleagues, and administrators about assessment decisions. Although each instructor exercises their academic freedom, it is also essential to share assessment practices that work and possible changes to implement. In these conversations, it is also important to carefully use language that conveys a clear understanding of the concept and practice of ungrading to avoid confusion, anxiety, misunderstandings, and reactions that prevent its implementation. Having these kinds of conversations can help shift the mind from a grade-focused to a learning-focused approach. A key element in these conversations is to ensure that the pedagogical reason behind the adoption of ungrading practices is not only clear but well understood (and this may take time).

Set a structure for ungrading

As with other elements of exemplary course design considerations, the structure of assessment practices is necessary. Adding a structure for ungrading assignments gives students a clear objective, steps, and flow that allow them to be consistent and accountable to their own learning goals and strategies.

Reflect on pedagogical and assessment practices

Instructors are invited to examine more in-depth their grading policies, why they grade in the way they do, what they are grading, and how they grade. In many cases, the path to ungrading is a response to dissatisfaction with grading policies. Aaron Blackwelder (chapter 2) says that, over time, he turned into a gatekeeper; he lost focus and was more interested in meeting institutional and “rigor” requirements than building relationships with students. His students had turned into competitive grade seekers. He questioned what a grade really suggests and posits that grades fail to communicate learning. The fact that grading allocates a specific number or letter that can bring some negative feelings to students, can also negatively affect the potential for learning. Sackstein (chapter 4) calls for a change in mindset to identify the way in which learning can be communicated and understood beyond the traditional use of numbers and letters. While Blum also argues for assessing the entire learning experience (with portfolios, for example), Sacksatein suggests considering changes in the language of grading which can provide students with an opportunity to shift the way they feel and think about their own learning.

Teach students to view mistakes as a necessary step in the learning process

Instructors are invited to reflect on how traditional grading practices are punitive, dehumanizing, and demotivating. Gibbs (chapter 6) points out that a system that punishes students for making mistakes reinforces the notion that all learning is flawless and therefore mistakes need to be avoided. Ungrading, on the other hand, aims to implement and cement the idea that learning is a process that needs constant feedback for that learning to be consolidated. Therefore, students need to be given opportunities not only to learn from their mistakes but to act on them in an interactive way. This requires instructors to plan for assessments that include steps for review (e.g., self, peer) to help the student build their skills, and knowledge over time.

Care for students and their learning

Instructors are also invited to demonstrate more explicitly that they care and validate students’ work. Further, Gibbs (Chapter 6) argues that her teaching philosophy is better summarized by the word “freedom”, the freedom that learners have to learn and grow at their rhythm and the freedom to make mistakes and learn from them. The role of the instructor is then to be supportive in that process through feedback and empathy. Ungrading, as it is overall discussed throughout the book, does not mean that there are no assessments or grading at all. On the contrary, the assessments should focus on helping students build their knowledge and understanding in less stressful ways, allowing students to build learning habits, develop creativity, become better communicators, and connect to their lived experiences and contexts. Caring for students also involves valuing their identity as learners and what they bring into the learning environment.

Be aware that ungrading can increase student anxiety and uncertainty

It is critical that instructors who are considering ungrading be cognizant that it involves a high level of anxiety and uncertainty on the part of students. Let’s recognize that students are so used and “conditioned” to grades that they will find it confusing not to have a grade associated with each assignment in the course. Many students consider being successful if they score a perfect grade which can be overwhelming and obscure the value of learning. Instructors who adopt ungrading should explain why and how ungrading will be done in certain classes. This will add transparency to the expectations and assumptions that instructors have about students.

Implement student voice and choice supported with personalized feedback

Instructors can help students take ownership of their learning through hands-on, real-life activities that allow students to use the content they are learning in projects of their interest, conduct research, and solve problems. Students can choose their topics and projects and the instructors can guide them to narrow topics and ensure the projects are feasible within the course timeframe. Consider feedback as a formative assessment approach that enables students to make choices about their learning strategies and needs to improve their learning tasks. Sackstein (chapter 4 ) suggests teaching students to collect feedback and identify the strategies that work for different kinds of assignment revisions. This way, students can develop better strategies that move them from lower-thinking to higher-thinking processes.

Since ungrading promotes the use of student-self assessment and reflection practices, it implies that instructors will need to personalize and tailor feedback to meet students where they are. In addition, instructors can consider setting a culture of feedback (Gibbs, chapter 6) where instructors teach students to use feedback to improve their work, provide peer feedback effectively, and see the value of learning from their mistakes.

Promote peer support

Authors of several chapters in this book have posited that students are more likely to give each other better feedback in the absence of grades. This kind of feedback can allow students to help each other, learn from one another, expand their awareness of their own understanding, and develop skills for life. Peer support will also help students build their confidence and autonomy to learn from each other.

Trust students

One critical aspect of assessment is trust –trust that students do the work they are expected to do by themselves. Instructors have legitimate reasons to express their concerns and create course policies about academic integrity that lead them to adopt plagiarism systems and surveillance tools to monitor and proctor students’ work. In adopting ungrading, trust is fundamental to change the way learning and performances are assessed. It involves helping students think differently about what it means to learn. Instructors can help students evolve in their approach to learning to move away from grades to focus on their learning by including in assessments strategies for building capacity for metacognition, confidence in their skills, life-long learning goals, and owning their learning.

Ungrading does not mean instructors don’t grade and students don’t receive grades on their work. Ungrading, as posited by the authors in the Ungrading book, is a mindset to approach student learning differently. In the second part of this blog, I will share the types of ungrading practices, implications, and challenges as presented in the book.

References

- Coghlan, S., Miller, T. & Paterson, J. (2021). Good Proctor or “Big Brother”? Ethics of Online Exam Supervision Technologies. Philos. Technol. 34, 1581–1606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00476-1

- Eyler, J. (2022, March 7). Grades Are at the Center of the Student Mental Health Crisis. InsideHigher Ed. [Blog]

- Kohn, A., & Blum, S. D. (2021). Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead). West Virginia University Press.

- Shi, T. (2022). Assessment Design: Ideas from Ungrading Book. [Ecampus blog]

- Stommel, J. (2020, February 6). Ungrading: an FAQ. [Blog]

- Talbert, R. (2022, March 30). Ungrading after 11 weeks. [Blog]