Over the past few years, Higher Education (HE) has been called to action in response to the rise of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools. As Artificial Intelligence (AI) becomes more autonomous and capable, proactive steps are needed to preserve academic and learning integrity. This article will explore tangible strategies educators can apply to their unique program and course contexts. Only slight adjustments may be necessary to support learning processes and capture evidence of learning, as changes will build upon the excellent work that is already occurring.

Initially, the focus in HE was on understanding the potential impact these tools would have on teaching and learning. Awareness of GenAI capabilities, limitations, and risks has been acknowledged with great care. Today, the tools are now being tested, and educators are envisioning how to use them for various purposes (e.g., productivity, creativity). Integration of these tools has begun with the aim of supplementing and enhancing human learning. As we move forward, concerns with regard to academic and learning integrity become increasingly prominent.

Meet Agentic AI

Recently, I had the opportunity to attend the Quality Matters Quality in Action conference, where I attended the session Ensuring Academic Integrity and Quality Course Design in the Age of AI. The presenter Robert Gibson, Director of Instructional Design at WSU Tech, shared about an Artificial Intelligence (AI) innovation now available to the public (and our students)….meet Agentic AI!

Your new Agentic AI assistant no longer requires you to be an expert prompt engineer. These tools are designed to achieve specific and clear goals with minimal human supervision or oversight. Engagement in complex reasoning, decision making, problem solving, learning from new information, and adapting to environments can occur autonomously (Gibson, 2025; Schroeder, 2025; Marr, 2025). These new Agentic AIs can even work together to form what is known as an Orchestrated AI. Think of this as an AI team working collaboratively to accomplish complex tasks. Agentic AI has already demonstrated the capability to create and complete online courses. What does this mean for Higher Education?

Now more than ever, we need to come together to collectively reinforce academic and learning integrity in online and hybrid courses. Preserving the quality of our institutional products and credentials is essential. Equally important are the students who will apply their OSU-acquired knowledge and skills in the real world. The time to be proactive is now.

Where and how should I start?

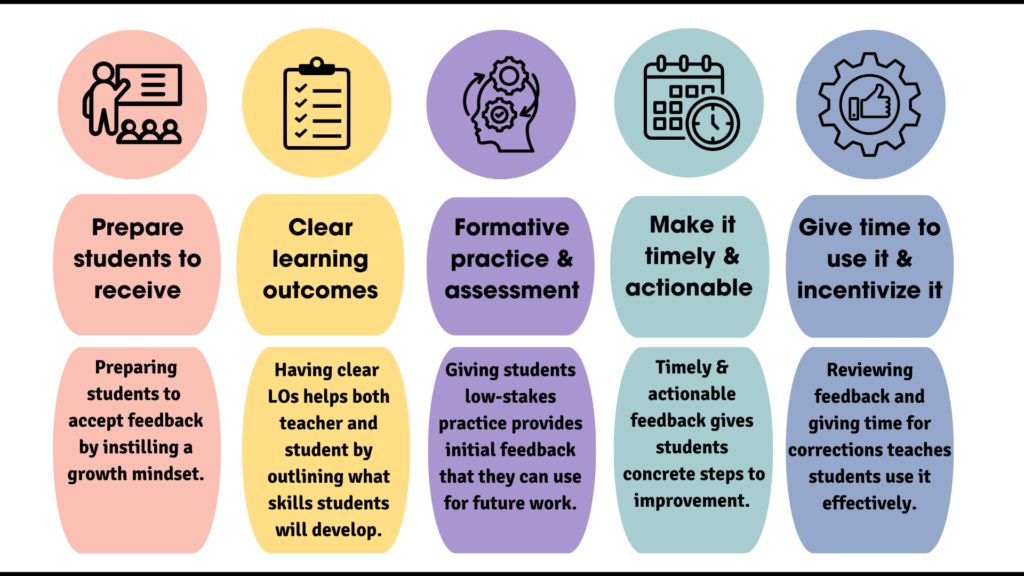

A good starting point is to evaluate assessments that AI can complete. Running an assignment through a GenAI tool to see if it can complete the task, with relative accuracy, can produce helpful insights. Next, consider modifications to pedagogical approaches and assessment methods. The goal is to design assessments to produce and capture evidence that learning is taking place. This could include assessments that are process-oriented, focus on skill mastery, are personalized, incorporate visual demonstrations (e.g., video), and/or integrate real-time engagement (Gibson, 2025).

What might a reimagined activity look like?

For example, let us say an instructor uses case-based learning in their course, and small groups discuss real-world scenarios on a discussion board. This activity could be reimagined by having students meet virtually and record their discussion. During their real-time interaction, they examine a real-world scenario, identify associated evidence, present examples, and share their lived experiences. This would be similar to how students conduct group presentations currently. This approach could be enhanced by shifting the focus to the learning process, such as arriving at ideas and cultivating perspectives (i.e., learning, growth, development). This would be in lieu of having students find a right or wrong answer (Gibson, 2025). This approach encourages students to engage substantively, co-construct knowledge, and work together to demonstrate learning. After participating in the activity, each student could create an individual video presentation to synthesize their learning. A synthesis video could include discussing their initial perspectives (Where did I start? – prior knowledge activation), how those initial perspectives evolved (What was my cognitive process? – metacognition), what new knowledge is needed (gap analysis), and how my perspectives and knowledge change (learning reflection). This method reinforces academic and learning integrity by validating that students are learning and achieving outcomes (Bertram-Gallant, 2017).

Reflect! Take a moment to reflect on how you know that students are learning in your course(s). What evidence do you have?

While the potential for academic dishonesty cannot be entirely controlled, there should not be an assumption that students will use these tools in their coursework just because they are available. Take a moment to examine the Ecampus Research Unit’s research, “Student Perceptions of Generative AI Tools in Online Courses.” This research study explores online students’ perceptions, understanding, and use of GenAI tools. The study found that most students had not been using GenAI tools in their courses, but rather, they were primarily using GenAI tools within professional contexts. Students noted that they understood that using AI in their careers would be necessary. However, strong concerns were articulated around inaccuracies, biases, lack of reliability, propagation of misinformation, and that the use of the tools is not in alignment with their personal values and ethics. (Dello Stritto, M, Underhill, G. and Aguiar, N., 2024).

How can academic and learning integrity be reinforced?

Educators can foster academic integrity in a way that drives students’ internal motivation, self-determination, and desire to demonstrate their learning because they value the work they are doing. A multifaceted developmental approach that fosters a culture of academic integrity using various strategies in concert with one another is key (Bertram-Gallant, 2025), as no single approach can serve as a definitive solution.

- Integrity teaching – Taking on the role of an active guide during course delivery and meeting students where they are developmentally is essential. This may include teaching students how to engage in critical thinking around the use of AI tools, connect the value of academic and learning integrity to their future profession, how to make well-informed decisions, and how to leverage metacognitive strategies when engaging with AI.

- Integrity messaging – This approach is one that can be most effective if holistically integrated into a course. The content communicates that integrity, values, and ethics are normative within the course and will be held at the forefront of the learning community. Staged and timed messaging can be most helpful when targeted at different points in a course and as the complexity of academic work increases.

- Transformative real time experiential learning – Transformative experiential learning involves designing opportunities that generate new ideas for action, which can be applied to other experiences. These activities may include, but are not limited to, service learning, internships, hands-on collaborative activities (e.g., role play, point-counterpoint discussions), and demonstrations. By focusing on real-time engagement, this approach demonstrates learning and thereby reinforces academic and learning integrity.

- Deep learning – Learning opportunities focused on skill mastery and demonstration through staged attempts. This approach may necessitate a pedagogical shift focusing on development and growth (Bertram-Gallant, 2025).

Agentic AI brings exciting opportunities for the world but tangible challenges for HE. By intentionally designing assessments that lead students to demonstrate evidence of their learning and using facilitation strategies that foster a culture of academic integrity, we can harness the potential of AI to supplement learning. What is the end goal? To ensure that educational opportunities are designed to preserve and enhance learners’ critical skills and knowledge needed to thrive in their professional pursuits. Will you accept this challenge?

Ecampus Artificial Intelligence Tools Resource Inventory

- Trying to decide when and how to incorporate AI into your work? Take a look at the AI Decision Tree!

- Need a few quick, practical strategies to get started? These recommendations aim to improve learning for both teachers and students.

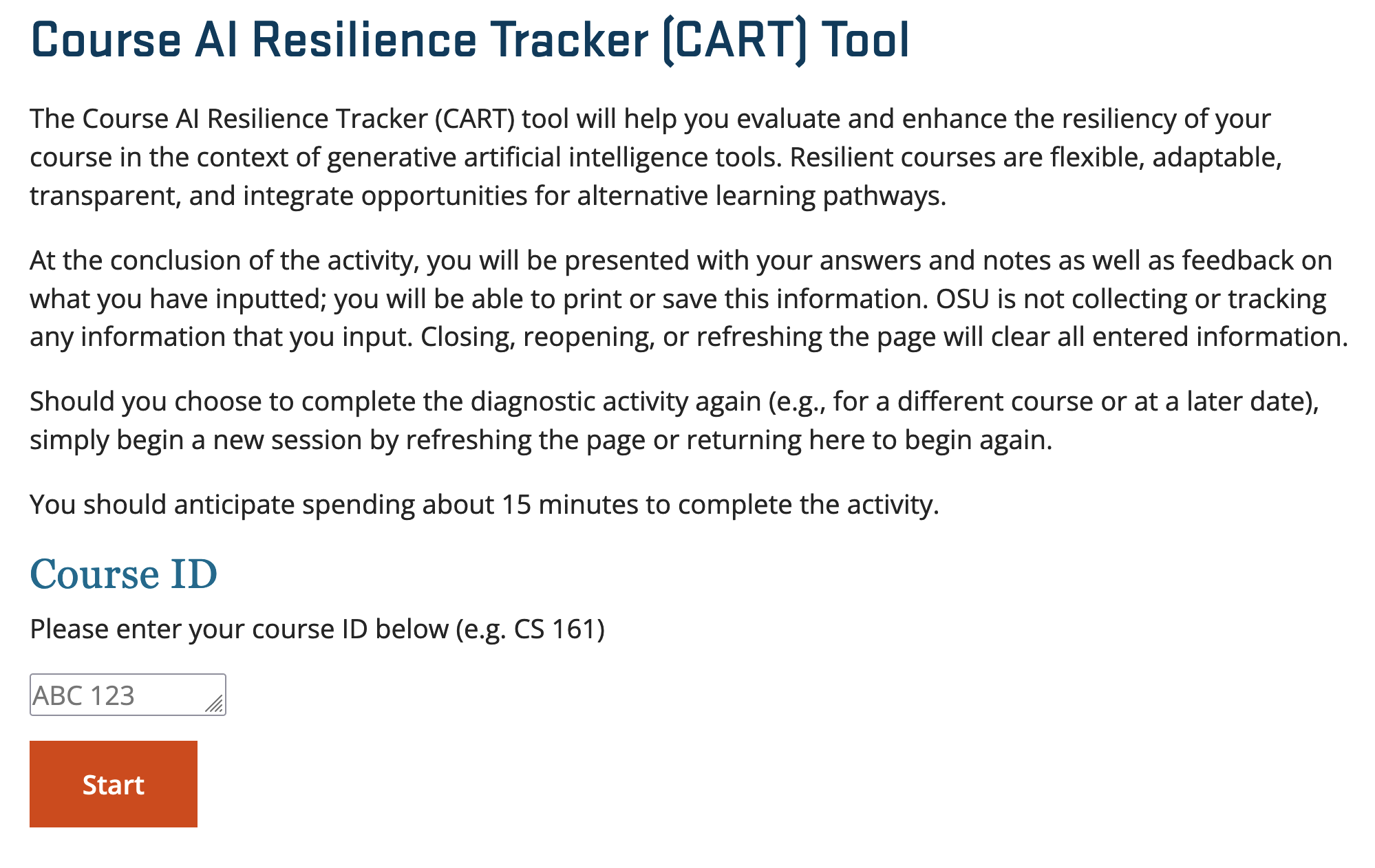

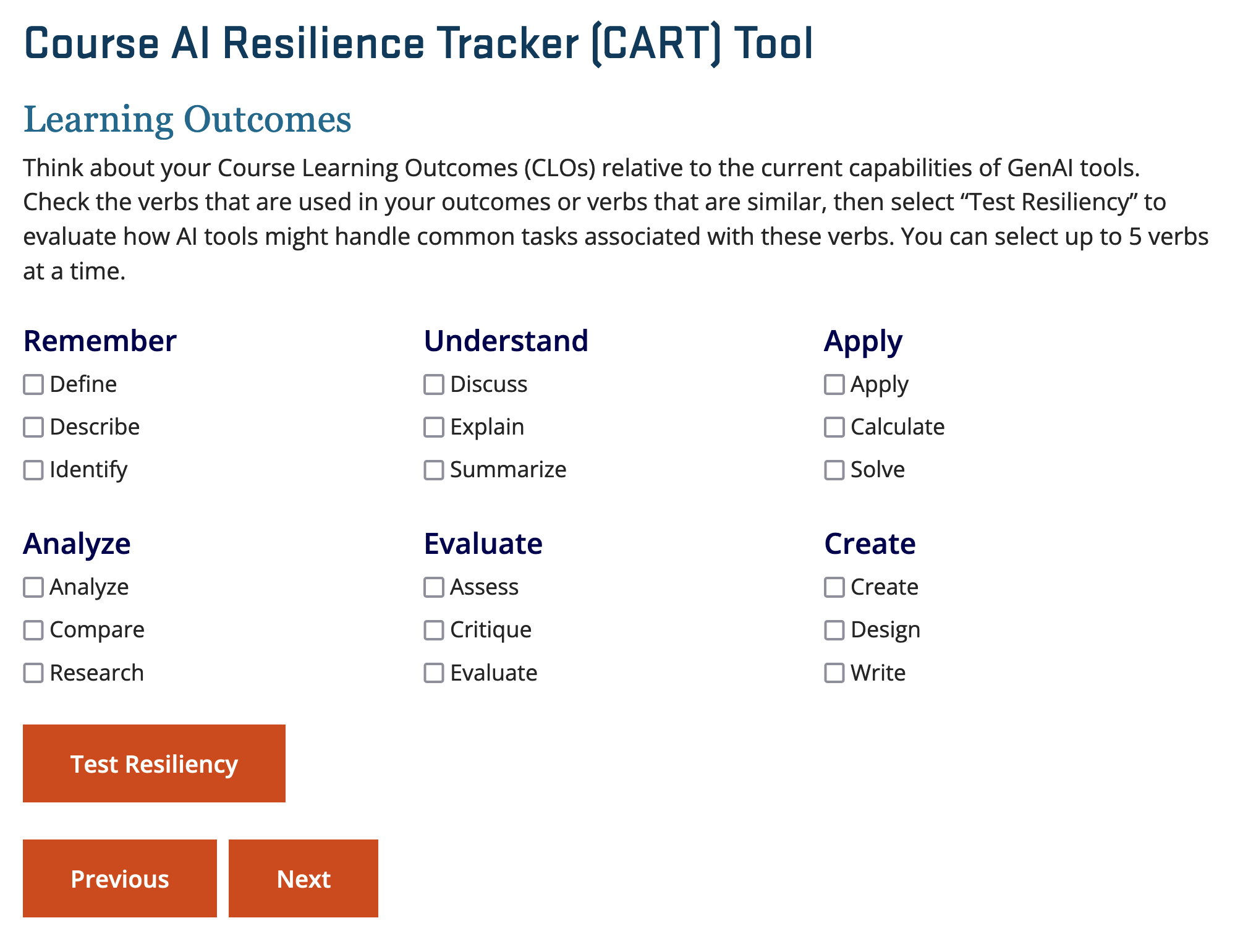

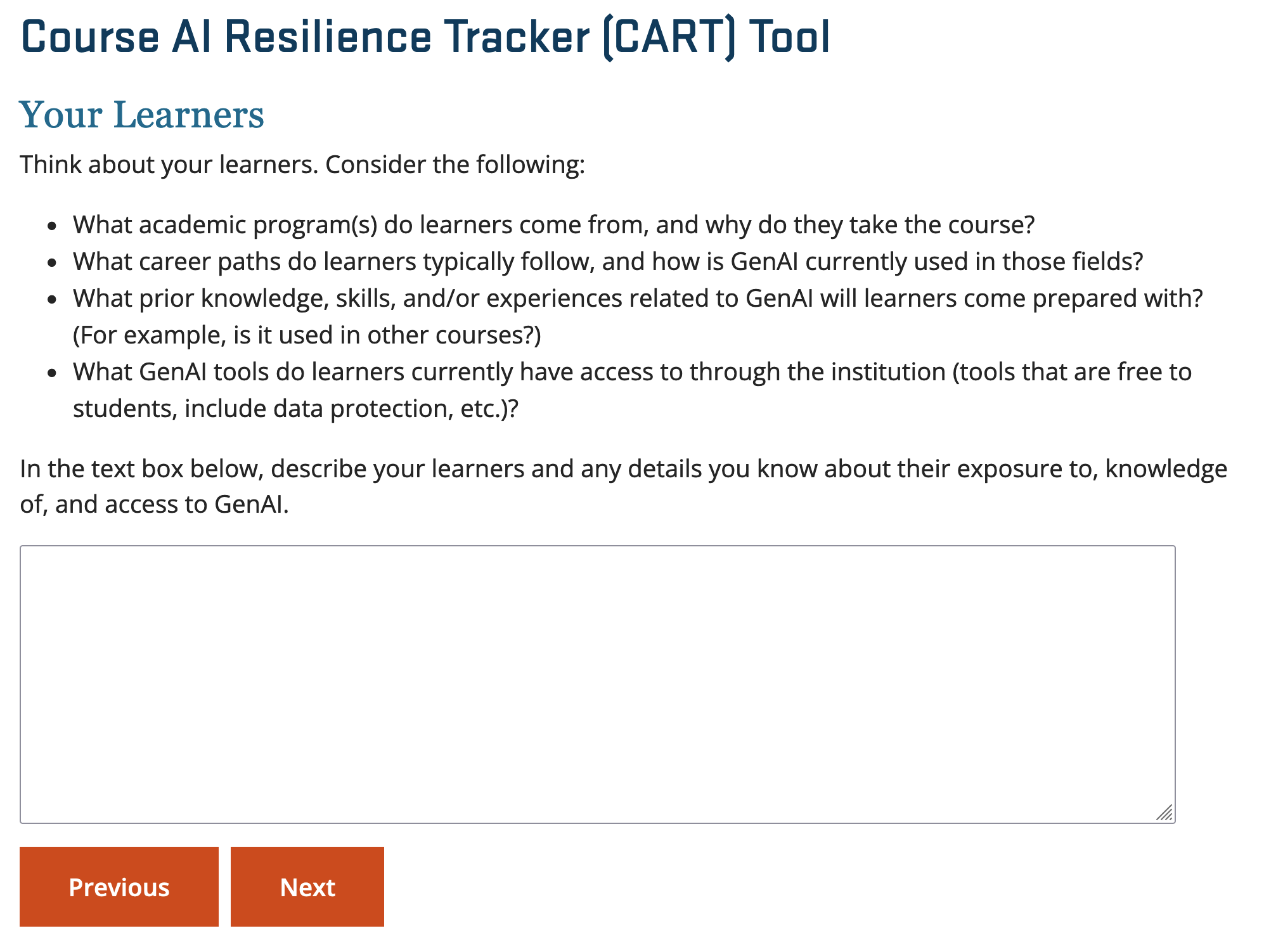

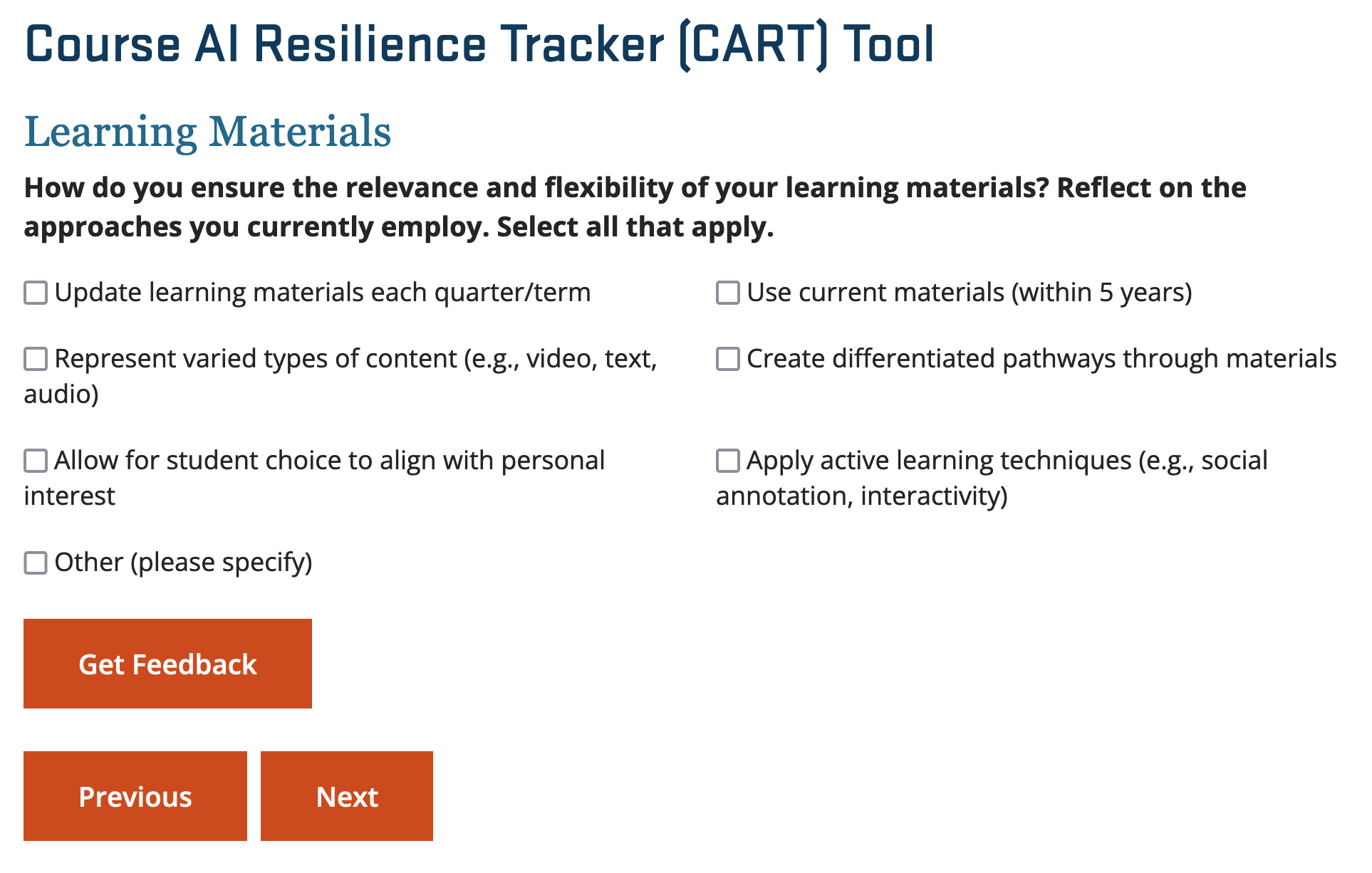

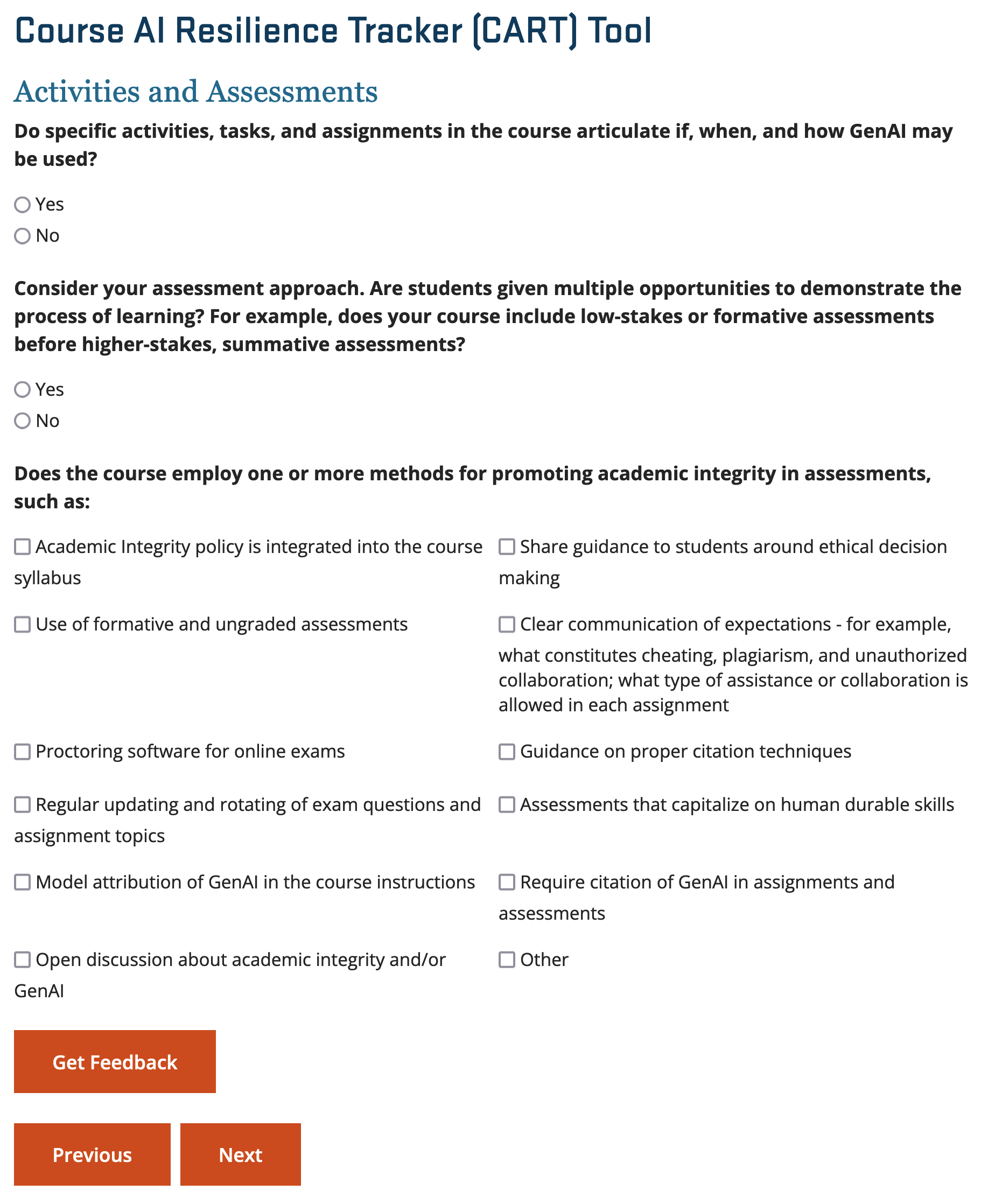

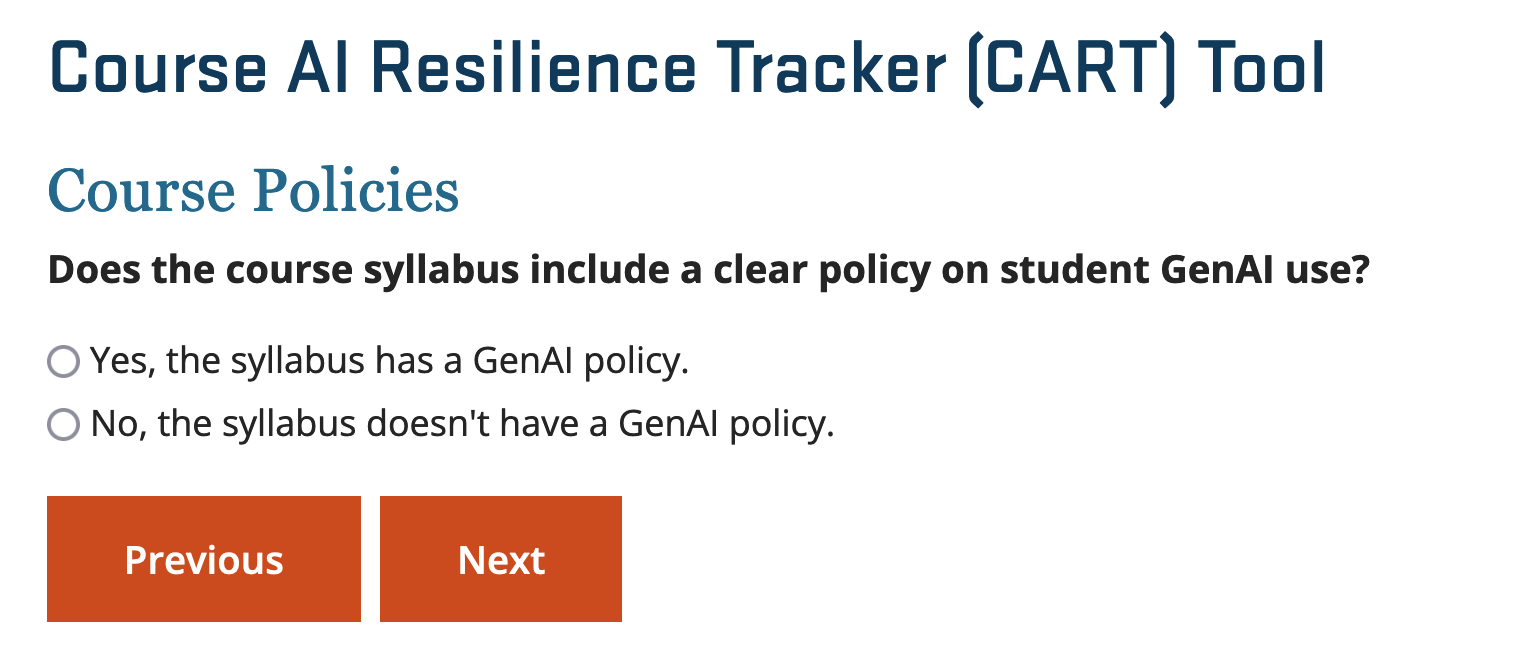

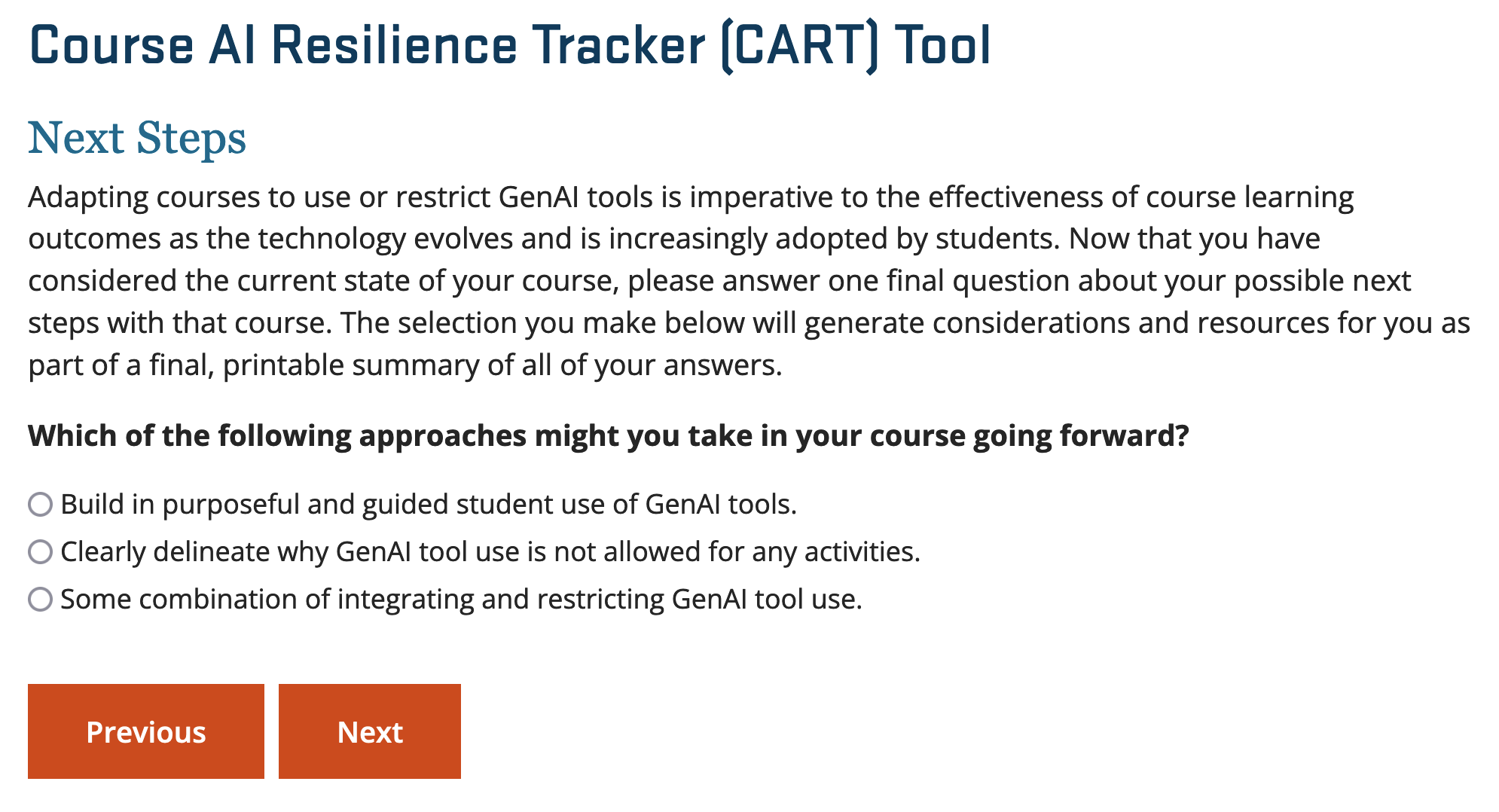

- Are you ready to evaluate and enhance the resiliency (i.e., flexibility, adaptability) of your course within the context of AI? Check out the new The Course AI Resilience Tracker [CART] interactive tool. This interactive tool can help you reflect on various course elements and will share personalized resources to help you get started.

- Review Bloom’s Taxonomy Revisited to explore how to emphasize distinctive human skills and/or integrate AI tools to supplement the learning process.

- Explore our AI Assessment Examples Library for assessment ideas designed to incorporate AI tools and strategies in your course and/or create more human-centric assessments.

Sources

- Bertram Gallant, T. (2017). Academic Integrity as a Teaching & Learning Issue: From Theory to Practice. Theory into Practice, 56(2), 88–94.

- Bertram Gallant, T. & Rettinger, D. (2025, March 11). The Opposite of Cheating: Teaching for Integrity in the Age of AI. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Dello Stritto, M. E., Underhill G. R., & Aguiar, N. R. (2024). Online Students’ Perceptions of Generative AI. Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit. https://ecampus.oregonstate.edu/research/publications/

- Gibson, R. (2025, April 10). Ensuring Academic Integrity and Quality Course Design in the Age of AI [Conference presentation]. Quality Matters Quality in Action 2025. Virtual.

- Marr, B. (2025, February 3). Generative AI Vs. Agentic AI: The Key Differences Everyone Needs to Know. Forbes.

- Purdy, M. (2024, December 12). What is Agentic AI, and How Will it Change Work. Harvard Business Review.

- Schroeder, R. (2025, February 5). Setting a Context for Agentic AI in Higher ED. Upcea.

About the Author

Connect with Ashlee! Email | Linkedin

Ashlee M. C. Foster, MSEd, is a seasoned Instructional Designer with the Oregon State University Ecampus Course Development and Training Team. With a profound commitment to supporting faculty and students in online teaching and learning, Ashlee’s mission is to design high-quality and innovative educational opportunities that foster transformational learning, development, and growth. Ashlee’s learning design approaches are grounded in research-based insights, foundational learning theories, and the thoughtful integration of industry-led practices. This ensures that each educational experience is not only effective but also engaging and relevant.