Machines take me by surprise with great frequency. – Alan Turing

This week we have a PhD student from the College of Engineering and advised by Dr. Maude David in Microbiology, Nima Azbijari, to discuss how he uses machine learning to better understand biology. Before we dig in to the research, let’s dig into what exactly machine learning is, and how it differs from artificial intelligence (AI). Both AI and machine learning learn patterns from data they are fed, but the difference is that AI is typically developed to be interacted with and make decisions in real time. If you’ve ever lost a game of chess to a computer, that was AI playing against you. But don’t worry, even the world’s champion at an even more complex game, Go, was beaten by AI. AI utilizes machine learning, but not all machine learning is AI. Kind of like how a square is a rectangle, but not all rectangles are squares. The goal of machine learning is to use data to improve at tasks using data it is fed.

So how exactly does a machine, one of the least biological things on this planet, help us understand biology?

Ten years ago it was big news that a computer was able to recognize images of cats, but now photo recognition is quite common. Similarly, Nima uses machine learning with large sets of genomic (genes/DNA), proteomic (proteins), and even gut microbiomic data (symbiotic microbes in the digestive track) to then see if the computer can predict varying patient outcomes. By using computational power, larger data sets and the relationships between the varying kinds of data can be analyzed more quickly. This is great for both understanding the biological world in which we live, and also for the potential future of patient care.

How exactly do you teach an old machine a new trick?

First, it’s important to note that he’s using a machine, not magic, and it can be massively time consuming (even for a computer) to do any kind of analysis on every element of a massive set. Potentially millions of computations, or even more. So to isolate only the data that matters, Nima uses graph neural networks to extrapolate the important pieces. Imagine if you had a data set about your home, and you counted both the number of windows and the number of blinds and found that they were the same. Then you might conclude that you only need to count windows, and that counting blinds doesn’t tell you anything new. The same idea works with reducing data into only the components that add meaning.

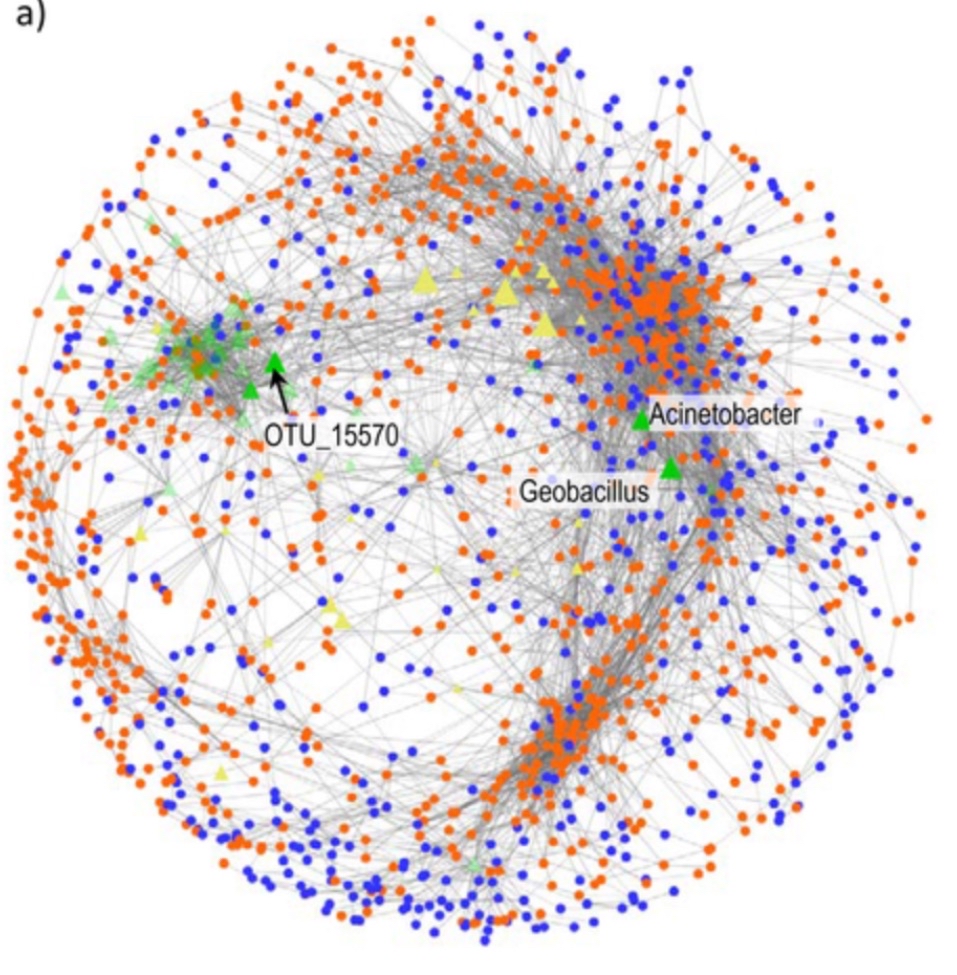

The phrase ‘neural network’ can invoke imagery of a massive computer-brain made of wires, but what does this neural network look like, exactly? The 1999 movie The Matrix borrowed its name from a mathematical object which contains columns and rows of data, much like the iconic green columns of data from the movie posters. These matrices are useful for storing and computing data sets since they can be arranged much like an excel sheet, with columns for each patient and rows for each type of recorded data. He (or the computer?) can then work with that matrix to develop this neural network graph. Then, the neural network determines which data is relevant and can also illustrate connections between the different pieces of data. Much like how you might be connected to friends, coworkers, and family on a social network, except in this case, each profile is a compound or molecule and the connections can be any kind of relationship, such as a common reaction between the pair. However, unlike a social network, no one cares how many degrees from Kevin Bacon they are. The goal here isn’t to connect one molecule to another but to instead identify unknown relationships. Perhaps that makes it more like 23 and Me than Facebook.

TLDR

Nima is using machine learning to discover previously unknown relationships between various kinds of human biological data such as genes and the gut microbiome. Now, that’s a machine you don’t need to rage against.

Excited to learn more about machine learning?

Us too. Be sure to listen live on Sunday November 13th at 7PM on 88.7FM, or download the podcast if you missed it. And if you want to stay up to date on Nima’s research, you can follow them on Twitter.