Have you ever considered that a virus that eats bacteria could potentially have an effect on global carbon cycling? No? Me neither. Yet, our guest this week, Dr. Holger Buchholz, a postdoctoral researcher at OSU, taught me just that! Holger, who works with Drs. Kimberly Halsey and Stephen Giovannoni in OSU’s Department of Microbiology, is trying to understand how a bacteriophage (a bacteria-eating virus), called Venkman, impacts the metabolism of marine bacterial strains in a clade called OM43.

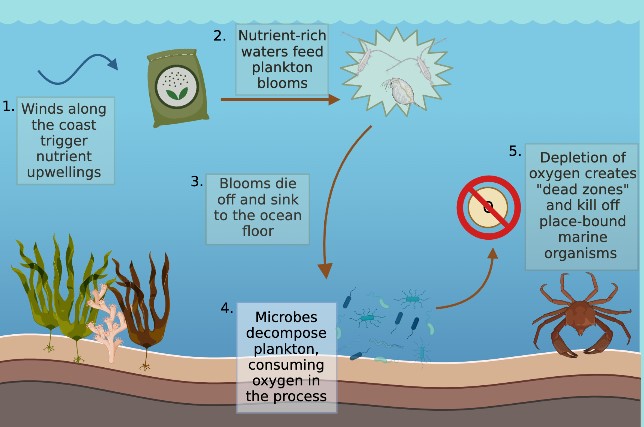

Bacteria that are part of the OM43 clade are methylotrophs, in other words, these bacteria eat methanol, a type of volatile organic compound. It is thought that the methanol that the OM43 bacteria consume are a by-product of photosynthesis by algae. In fact, OM43 bacteria are more abundant in coastal waters and are particularly associated with phytoplankton (algae) blooms. While this relationship has been shown in the marine environment before, there are still a lot of unknowns surrounding the exact dynamics. For example, how much methanol do the algae produce and how much of this methanol do the OM43 bacteria in turn consume? Is methanol in the ocean a sink or a source for methanol in the atmosphere? Given that methanol is a carbon compound, these processes likely affect global carbon cycles in some way. We just do not know how much yet. And methanol is just one of many different Volatile Organic Carbon (VOC) compounds that scientists think are important in the marine ecosystem, and they are probably consumed by bacteria too!

All of this gets even more complicated by the fact that a bacteriophage, by the name of Venkman, infects the OM43 bacteria. If you are a fan of Ghostbusters and your mind is conjuring the image of Bill Murray in tan coveralls at the sound of the name Venkman, then you are actually not at all wrong. During his PhD, which he conducted at the University of Exeter, part of Holger’s research was to isolate the bacteriophage that consumes OM43 bacteria (which he successfully did). As a result, Holger and his advisor (Dr. Ben Temperton, who is a big Ghostbusters fan) were able to name the bacteriophage and called it Venkman. Holger’s current work at OSU is to try and figure out how the Venkman bacteriophage affects the metabolism of methanol in OM43 bacteria and the viral influence on methanol production in algae. Does the virus increase the bacteria’s methanol metabolism? Decrease it? Or does nothing happen at all? At this point, Holger is not entirely sure what he is going to find, but whatever the answer, there would be an effect on the amount of carbon in the oceans, which is why this work is being conducted.

Holger is currently in the process of setting up experiments to answer these questions. He has been at OSU since February 2022 and has funding to conduct this work for three years from the Simons Foundation. Join us live on Sunday at 7 pm PST on 88.7 KBVR FM or https://kbvrfm.orangemedianetwork.com/ to hear more about Holger’s research and how a chance encounter with a marine biologist in Australia set him on his current career path! Can’t make it live, catch the podcast after the episode on your preferred podcast platform!