Subject matter experts in many fields have embarked on authoring projects with the goal of replacing traditional published texts or customizing content for specific learners’ needs, yet large-scale creation of open textbooks or series designed for language learners has been slower to gain traction (Blyth and Thoms, 2021). Efforts in this area have largely been limited to adapting existing OER materials (5R activities) for specific learning contexts or piecemeal creation of online activities to provide reinforcement of isolated language skills. Part 1 in this series outlines the potential benefits, limitations, and challenges that programs and instructors face when undertaking large-scale authoring projects to address the needs of language learners. The purpose of this second post is to offer guidance for creating open source language texts and present a framework for getting started.

Language Acquisition as an OER Subject Matter

Before getting into the nitty-gritty of creating an OER for language learners, it is worth pointing out how this process differs from open authoring projects for other disciplines. While OER writing projects come with inherent challenges regardless of the field, authoring comprehensive language learning content presents a unique challenge. One reason for this is that language teaching and acquisition involves complex sequencing and scaffolding of skills, language items, and linguistic concepts unique to the field of language acquisition (Howard and Major, 2004). An effective resource must present language items not only in the established order of second language acquisition, but also at the correct level for the learners at hand. The “correct level” is fluid and influenced by many variables (first language interference, motivation, metacognitive skills related to the process of learning a language, fossilization of rules, literacy in the first language, prior knowledge and educational experiences, and so on). While, say, writing a history text also involves expert scaffolding to ensure that content builds on what came before, there are fewer moving parts to align, and presentation and sequencing can and will vary from one subject matter expert author to the next. Effective language learning materials, on the other hand, are more like a house of cards that relies on complex relationships between a variety of aspects of the target language, language input, learning context, and characteristics of the learners themselves.

Language acquisition occurs when input is just beyond what students understand of a language (known as comprehensible input i + 1), so writing materials that consistently hit the sweet spot for learning is tricky even for the most seasoned language educator. In addition to presenting language in a specific sequence and at the appropriate level, authors must also consider how much new language content is enough at each stage and how to introduce, recycle, and reinforce this language through engaging and original texts as well as audios that present authentic and relevant contexts. All of this new content must then be aligned to learning outcomes related to both language form and function. Learners need not only the nuts and bolts of the language, but pragmatics are equally important—how is the language used in specific contexts and with a variety of interlocutors? What models will convey this information accurately in a way that is accessible at different levels of proficiency?

Understanding the social aspect of language is as important as the grammar and structure. Language proficiency involves much more than speaking and listening in a new language. All of the linguistic aspects must be delivered via content that also serves as a vehicle for familiarizing learners with the cultural and social contexts where the language is spoken. This should be done in a thematic way, weaving in social justice issues in a timely and relevant manner, sensitive to the complexity of the issues at hand. The author(s) must also be able to write engaging texts that present level-appropriate target grammar, vocabulary, and cultural information in activities that build upon each other or recycle the language previously taught. In addition to being linguistically sound, these original texts and audios must also demonstrate awareness and care for representation, integrating cultural and social justice topics relevant to the diversity of cultures, communities, interests, and social issues of a variety of speakers of the target language.

Creating language materials that incorporate all of these considerations requires a broad skillset beyond expertise in teaching the subject matter. Significant professional development and exploration may be necessary before embarking on expansive authoring projects for language learning. With careful coordination and planning, and an understanding of the process and support required, language programs, instructors, and learners stand to reap long-term benefits from creative, relevant, inclusive, and dynamic open resources. What follows is a suggested process and a sample framework for undertaking open source textbook production for language learning contexts.

Step 1: Survey of needs, resources, and intended uses

The first step in any authoring project is to identify the needs of a program and determine what kind of text will be used and how. This includes the extent of the textbook use within the department and also as a resource for the broader language learning community. A quality textbook resource can increase student autonomy and interest in language learning generally by providing accessible resources readily available to learners anywhere in the world (Godwin-Jones). At this stage, some questions to ask include:

- Who are your learners and what is their motivation for learning a new language?

- What kind of textbook needs to be replaced? What gaps do you seek to fill by replacing current text materials?

- How will the resource fit into the larger curriculum?

- Is the need for a single course text or a cohesive series to cover an entire level or multiple levels?

- Who is available to collaborate and what are their areas of expertise?

- What resources and support are available for the project?

- How will time and resources be accounted for?

- What is the timeline for implementation?

- Who will provide expert and outside peer review of the textbook materials?

- How will the textbook materials be maintained and updated over time to ensure long-term viability?

Most language programs involve extensive faculty collaboration. Instructors teach multiple courses across various levels. As such, it is important to promote broad participation in the planning stage to encourage instructor input, address concerns, and determine the scope of the implementation (e.g., across courses, levels). Gathering input on content and soliciting expertise among colleagues increases faculty buy-in and ownership of new materials.

Step 2: Identify the scope of your project

Once the shape of the project has been determined, it is time to outline the specifics of the resource(s) to be created. Determining the scope involves identifying learning outcomes. These are often mandated by the program, but they might also need to be rewritten or revised by the authoring team. Both the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) provide guidance on proficiency standards for world languages. Beyond language outcomes, it is also important to identify what the content goals are. This may involve generating a master list of topics, social justice and cultural themes to be addressed, and so on. At this stage, identify subject matter experts and any professional development needs. Who will participate as part of the core authoring team? Who will be responsible for quality control and review? Keep in mind that creating, reviewing, building, piloting, and maintaining comprehensive open language materials requires a significant time commitment, even if the goal is to create a single course text.

See ACTFL World Readiness Standards for Learning Languages

Step 3: Collaborate on a framework scope and sequence

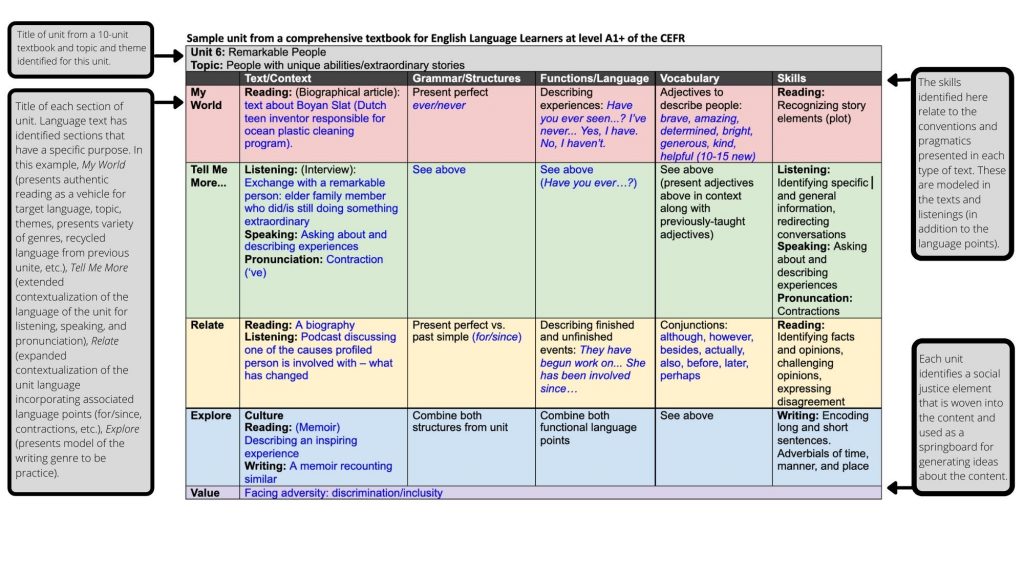

The importance of this stage cannot be understated, particularly when multiple authors and stakeholders are involved. Once the themes, topics, outcomes, and other aspects of the materials have been identified and divided up into learning segments (levels across a series, units of a text, etc.), it is time to write the scope and sequence, which is basically a detailed outline. This outline should clearly show how everything fits together and serves as a framework for authoring materials that weave together language function and form, grammar points, text genres, readings, audios, pronunciation, vocabulary, practice activities, interaction, cultural and social justice themes, topics, etc.—all with attention to a logical progression, order of acquisition, recycling of language items, and student engagement.

Let’s take a language text for English language learners as an illustrative example. If the grammar point for a learning segment is the present perfect tense, what types of contextualized content elicits that structure naturally? Perhaps a short biography representative of one aspect of the culture can serve this purpose. Reading and audio texts might present a person’s life experience so far. This offers an opportunity to consider whose lived experience will be represented via this text. Which vocabulary items are crucial for using the language around this topic? How much vocabulary will be new and how much recycled? Using the present perfect form as an example, we might focus on a number of participial adjectives and the prepositions for/since (She has been interested in … since…). Language teachers as subject matter experts should have no trouble identifying these items regardless of the target language—this is how SLA comes into play. They teach this content all the time. The challenge is in putting it all together across units. That is, in addition to the grammar, punctuation, pronunciation, and writing systems (depending on the writing system of the language at hand) authors need to consider how the language builds on what was previously taught, how much is enough to present in each segment, what the cultural and social topics to be woven into authentic texts are, etc. A good scope and sequence defines all of this. For this reason, settling on a solid scope and sequence will require extensive coordination across subject matter experts, departments (in many cases), and in all cases, several rounds of review and revision before any writing begins.

Step 4: Write and build

Once a final scope and sequence is in place and an authoring team has been identified, it’s time to start creating materials. Some questions to guide this stage include:

- Who will write the text and audio scripts?

- Who will provide diverse voice talent for audio texts?

- Who will record and edit audio?

- Where will the content be hosted and who will create it? (If using a tool such as Pressbooks, consider training for materials developers.)

- What platforms will be used for any interactive content? (H5P, Quizlet, Playposit, etc.) and who will build these?

- Where will the interactive repository be stored?

- Who is responsible for acquiring Creative Commons images and maps?

- How will accessibility be ensured?

- What learner analytics will be gathered and how?

Because most of the activities in a learning segment tend to spring from the reading and listening input, it may be helpful to start with writing all of the texts for a level or course before creating the rest of the content. Audio and written texts must expose learners to a wide range of genres and text types (Tomlinson, 2012), so it may be useful to start by generating a list of genres to be covered. The texts, whether they are original or curated from online sources, must be reviewed and revised or adapted to ensure they contain the necessary language at the appropriate level, generate interest, employ the intended tone and voice for the genre, follow identified themes, incorporate social justice and cultural topics, and are accurate (in the case of non-fiction texts). If the content is curated, it needs to be reviewed for copyright and accessibility.

Throughout the authoring stage, frequent check-ins among authors and reviewers can help to ensure quality, authenticity, inclusivity, and adherence to the determined scope and sequence.

Step 5: Review and revise

Just as at every other stage of the process, peer reviews and revisions should be coordinated so that there is continuity in the editing process. It is important to enlist the help of internal and external subject matter experts. Assign different review tasks (big picture reviews of content and continuity along with detailed reviews of the language presentation) and provide each with review rubrics or guidelines to streamline feedback. External reviewers outside of the organization can help provide neutral insight. Enlisting the help of those with expertise in social justice topics, regional cultural perspectives, and different varieties of the language can help ensure accuracy, representation, inclusivity, and engagement. Be sure to review feedback as a team to reach an agreement on how to approach revisions to draft materials.

Here is a sample rubric for reviewing original course materials, but rubrics should be adapted according to the scope and sequence and goals of each project.

Step 6: Implement and iterate

Finally, it is time to pilot your new OER, but you aren’t done yet! Deliver the content to learners and collect their feedback as well as input from your teaching team. Keep in mind that an OER can be a work in progress, and one advantage of an open textbook is that it can be an evolving resource. Each iteration should involve coordination and input from the team who will be using the materials. Share your new resource widely. A high-quality OER opens the door for resource sharing with a broad community of colleagues, building visibility for the language program and lending credibility among colleagues around the world for the subject matter expert creators (Blyth and Thoms, 2021).

Step 7: Create a plan for long-term viability: updating materials, quality control, and access

While creating an open source textbook for language learners can be a continually iterative process, once the new materials reach a point of stability and all stakeholders are satisfied with the product, authors or departments need to create a plan for maintaining the materials. Unlike costly textbooks which quickly become outdated, open access resources are easier to update (once the initial investment in time and resources has been made), save students money, and expand access to learners everywhere. The key is to create a plan for longevity so that updates are systematic, incorporate learner and instructor input, and are reviewed for quality control. The beauty of an OER for language learning is that it offers the opportunity to democratize teaching and learning by being responsive to the changing landscape of social justice education, shifting cultural influences, evolving characteristics of language learners, and distinct learning contexts.

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL)

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages – Companion Volume (2020)

Blyth, C. S., & Thoms, J. J. (Eds.). (2021). Open education and second language learning and teaching: The rise of a new knowledge ecology. Multilingual Matters. https://www.multilingual-matters.com/page/detail/?k=9781800411005

Godwin-Jones, Robert. “OER Use in Intermediate Language Instruction: A Case Study.” CALL in a Climate of Change: Adapting to Turbulent Global Conditions – Short Papers from EUROCALL 2017, 2017, pp. 128–134., https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2017.eurocall2017.701.

Howard, Jocelyn & Major, Jae. (2004). Guidelines for Designing Effective English Language Teaching Materials.

Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 45(2), 143–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528

(image from pxfuel.com)

(image from pxfuel.com)