David P. Turner / February 9, 2026

Introduction

The defining feature of the Anthropocene Epoch is that humanity – through the activity of mass technology (the technosphere) – has become the equivalent of a geologic force. The geological history of planet Earth now includes an anthropogenic rupture characterized by a rapidly changing atmosphere and climate, as well as a wave of extinctions among plant and animal species. The negative impacts of these self-induced global environmental changes on the human enterprise are already being felt, and in coming decades will cause widespread misery and death.

Humanity has begun to coalesce in the face of this threat, and is scaling up programs of mitigation (reduction of greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (e.g. sea walls). The results thus far, however, are rather feeble. Here, I want to survey three cultural-intellectual responses to western Modernity in hope of finding inspirational ideas on how humanity (“we”) might better address global environmental change issues.

There are certainly many ideas from outside the western cultural perspective that are relevant to this project of building a new model for how humanity interacts with the Earth system. But in this blog post I will be admittedly western centric for the sake of coherence.

Modernity, and Pushbacks against it from Modernism, Postmodernism, and Metamodernism

Modernity is a historical period in the course of western civilization extending from the 16th Century onward to the present. It began with the Enlightenment, when religious dogma as a way of knowing was displaced by reason and science. A core event was the Industrial Revolution, which fostered a proliferation of machines and buildings, along with a global infrastructure for travel and communication. Capitalism is the operating system of Modernity. Relentless economic growth is a characteristic feature. The grand narrative of Modernity is progress – elaborated in the form of improving technology and quality of life. The many downsides of Modernity include two world wars, rising inequality, and the aforementioned global environmental changes.

Cultural theorists have identified three movements, or constellations of ideas, which have arisen since around 1900 as a critique of Modernity. The modernism, postmodernism, and metamodernism movements are sequential, but with substantial overlaps. Modernism flourished from around 1900 to 1960, postmodernism from around 1960 to 2010, and metamodernism from around 2010 to the present. These movements do not represent political ideologies, rather different ways of thinking.

They have of course inspired vast troves of lectures, articles, books, and videos, within both academia and popular media, but here I want to evoke only a few ideas or themes within each movement that might be extracted as contributions to a new paradigm for the relationship of humanity to the rest of the Earth system.

Modernism

In the early 20th Century, before World War One, countries around the world were exuberantly pursuing what I have called the “buildout of the technosphere”, i.e. the extension and thickening of the network of cities, factories, machines, roads, and support infrastructure that now cloaks the planet.

Great masses of people were drawn into this network as factory workers, construction workers, ship builders, administrators, and the like. The natural environment was treated as an infinitely malleable background, and environmental quality was largely ignored.

Science advanced rapidly, but served as both a boon (e.g. nitrogen fertilizer) and a bane (e.g. nerve gas) to civilization. National leaders were feeling so inspired by all the “progress” that they stumbled into the First World War, with all its mindless waste and horror.

Modernism as a cultural-intellectual movement arose as a critique of this trajectory (i.e. the trajectory of Modernity). Writers, philosophers, architects, and artists of many types began to question the linearity, regimentation, environmental degradation, and human degradation (including colonialism) that were features of Modernity.

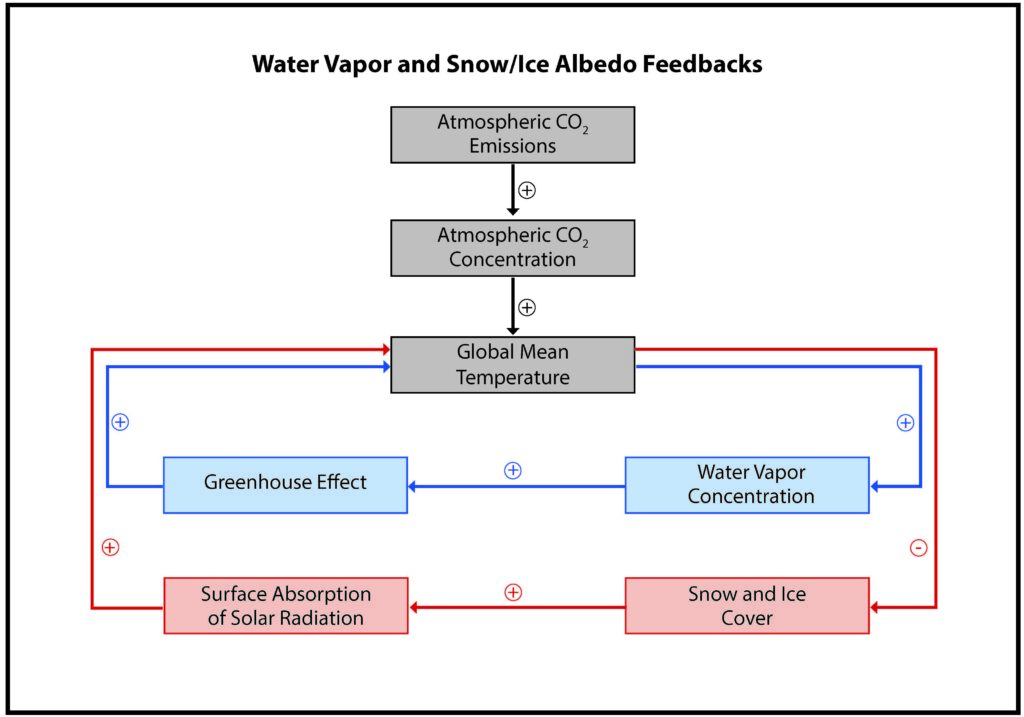

A significant theme that surfaced early on was the idea of nature as a force greater than humanity. Modernist writers understood nature as something more than just a background to industrial development. Joesph Conrad, in The Heart of Darkness, saw nature as “an implacable force”, something we degrade but cannot ultimately control. This idea is relevant to the present because we are now beginning to recognize nature – framed as Gaia (the quasi self-regulating Earth system) – as having agency. James Lovelock, early Earth system scientist and popularizer of the Gaia narrative, referred to “The Revenge of Gaia” in the title to one of his books. Humanity must now aspire to cooperate with or manage Gaia.

A second useful theme from modernism is “interiority”. In contrast to the realist novels of the 19th Century (e.g. George Eliot’s Middlemarch), the novels of early modernism often spend considerable time inside the heads of the protagonists.

One thing that occupied those minds was maintaining a personal relationship to the natural world. Characters in D.H. Lawrence novels often espoused that an antidote to the environmental and intellectual squalor of industrialization was an engagement with blood, flesh, and soil. The Birken character in Women in Love strips off his clothes and writhes around on the ground, communing with a bed of primroses. A hundred years later, the disconnect from nature induced by Modernity is ever greater. We need modernism’s reminder to immerse ourselves in nature, to engage with it. We might thus come to love and nurture it instead of degrading it. The aggregate effect of many caring individuals could be significant societal change.

A third modernist writer pushback was against the increasingly regimented and mechanical sense of time that is imposed by industrialization. Virginia Woolf compresses much of Mrs. Dalloway into a single day, and stretches the life of her protagonist in Orlando over multiple generations (even alluding to a change in climate over that period). Woolf, James Joyce, and others tried to break out of conventional temporal framing.

This concern with compressing and stretching time is relevant to contemporary issues because the advent of the Anthropocene means we must juxtapose historical time with geological time. Comprehending humanity as a geological force requires that we place the near-time environmental impacts of humanity (e.g. climate change) in the context of environmental changes happening over a geologic time scale. And we must firmly grasp scenarios for the Earth system extending into the distant future, scenarios that differ greatly depending on current investments in mitigation (e.g. how soon we accomplish a renewable energy revolution to reduce greenhouse gas emissions). Our capacity to mentally shift temporal perspective needs exercise.

Postmodernism

By the 1960s, the products of Modernity had come to include another World War, the threat of nuclear holocaust, and environmental decline at the global scale. Artistic and philosophical critique of Modernity proliferated, and the dominant critique began to be packaged as the postmodern movement.

The core orientation of postmodernism is a suspicion about “grand narratives” especially the narrative of continuous progress during the roll-out of western civilization. Postmodern philosophers maintained that what we call reality is constructed (made-up essentially) by the dominant socio-economic actors in society. Even the scientific epistemology was questioned to the degree that it claimed to be the only way to establish universal truths.

In literature, postmodern novels like DeLillo’s White Noise and Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow portrayed a world without reliable sources of authority, and immense ambiguity about every aspect of the human condition.

Postmodernism did not have much to say about the environment except perhaps to reject the environmentalist’s totalizing narrative of decline. However, if there is something worth saving from postmodernism for our purposes here, it would be having the vision and fortitude to question the whole direction that western civilization is headed, i.e. asking if it is really progress to precipitate a 6th Mass Extinction and a cataclysmic change in the global environment. Too many people today are not asking big questions.

Postmodernism itself can’t take us much beyond asking questions, but it certainly rattles the foundations of western self-regard.

Metamodernism

By the time of the 9/11 terrorist attack, cultural theorists had grown weary of postmodernism. Modernity was drifting towards apocalypse, and instead wallowing in a nihilistic labyrinth of deconstruction, perhaps something should be done about it.

The polycrisis that now besets humanity is clear to see. It includes environmental degradation at all scales, the emergence of AI as something that may become superior to ourselves in many ways, a rickety economic system based on capitalism that continues to generate vast inequality, and systems of governance at all scales that are disrupted by polarization and are inadequate to the demands of the times. We also face a metacrisis – an inner psychological turmoil induced by the pace and complexity of environmental, technical, and societal change. Our mental capacities seem to be incommensurate with the demands of the times. No wonder doom scrolling has become a global pastime.

The metamodern movement is a new set of ideas and concepts inspired by the deficits of Modernity and daring to be forward looking.

Meta- here implies oscillation between modernism and postmodernism, but it also allows for emergence above them and beyond them.

Like modernism and postmodernism, the metamodern movement is not fundamentally political, i.e. does not advocate any particular stance on the many political polarities of the day. Metamodernism is rather a way of thinking that will hopefully birth a new version of humanity, a version able to accomplish the needed “Great Transition” away from the polycrisis. The meta- move is to take a step back to gain perspective.

I’ll focus on four critical metamodern concepts. For this blog post, I want to concentrate on the ways these concepts might inform how we think about the environment.

1. History. Metamodernism recognizes the benefits of Postmodern skepticism about grand narratives. Nevertheless, it maintains that we can sincerely take a stand on momentous issues like massive anthropogenic environmental change and envision a non-calamitous future.

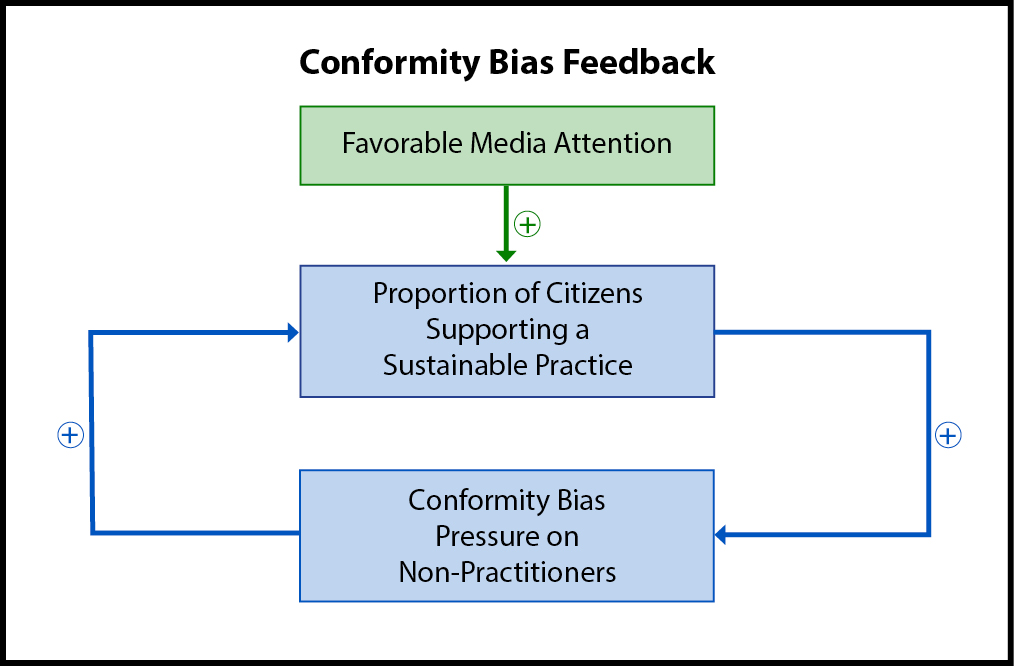

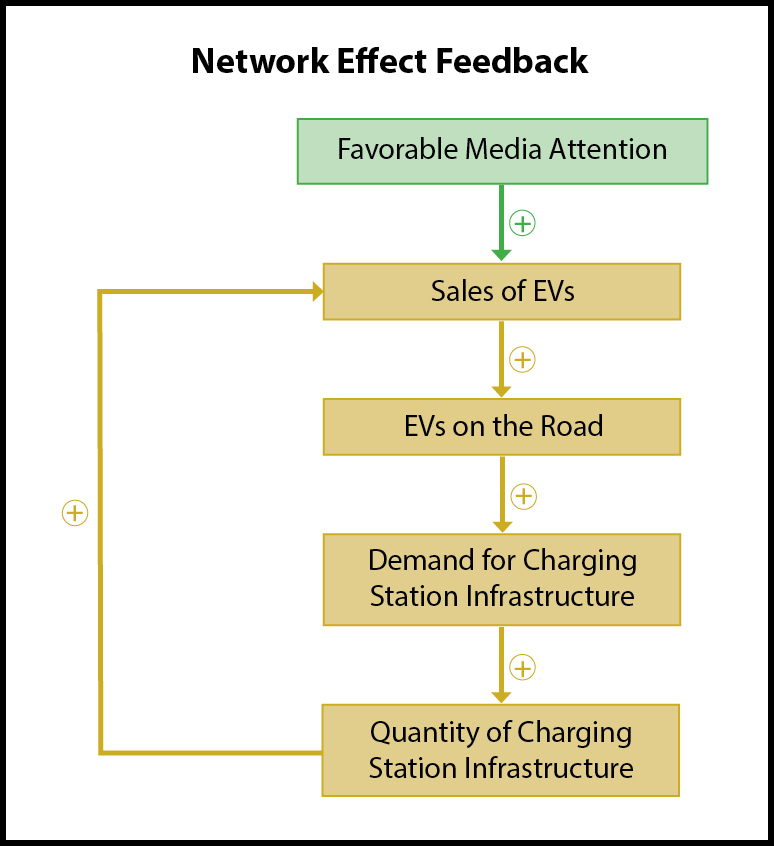

2. Interiority. Metamodernism takes a step beyond modernism’s call to pay attention to interiority by calling for deliberate personal growth. We each have the capacity to grow in terms of self-awareness, emotional depth, and intellectual breadth – but doing so requires focus and effort. Digital Modernity strives to consume our attention, leaving few inner resources available for personal reflection and self-development. However, personal growth is now entangled with the polycrisis. Individual decisions about consumption (EV vs. gas guzzler), and about politics, matter.

3. Intimacy. In late Modernity, a person is essentially a consumer. Our relationships with each other are largely transactional. The new ask from metamodernism is that we bind ourselves to the other humans on this planet based on our shared predicament. We know the causes of rapid climate change and the 6th Extinction, and we share the responsibility to do something about them.

4. Context. The fragmentation of life in Modernity keeps us juggling many balls simultaneously. Metamodernism asks us to step back, or forward, or above, each ball. There is no fixed frame of reference, but always a need for context. In terms of systems theory, we need to construct hierarchies and holarchies that permit changing the spatial and temporal scale of our perspective. Metamodernism asks that we never wholly rest in one context.

Two recent novels that qualify as metamodern are Ian McEwan’s Solar and Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry of the Future. In Solar, McEwan satirizes his main character (Beard, a theoretical physicist) as having good intentions with respect to the environment, but deep human flaws that prevent him from accomplishing much. Besides examining the interiority of Beard, McEwan uses the novel to educate the reader about the environmental crisis and possible technologies to address it. That oscillation makes it metamodern. The oscillation or tension in Ministry is between the exceedingly dire environmental trajectory portrayed for the near-term future vs. a long-term future in which humanity manages to deal with the vested interests that block climate change mitigation.

A New Paradigm

The selection of ideas here from modernism, postmodernism, and metamodernism provides only a glimmer of the constellation of ideas needed to create a new paradigm (technobiosphere symbiosis?) for the relationship of humans to the Earth system.

However, that glimmer has significant implications.

- Linear time is disintegrating. Humans will be dealing with past and present actions (e.g. carbon emissions) for centuries to come. We have to project ourselves into the future and cultivate a sustainable world. The distant past and the distant future matter.

- Our sense of space is also destabilizing. The nation has been a spatial reference for Modernity. Now, we have to think globally. The biosphere is a thing, the technosphere is a thing. Earth is our home.

Relevant ideas for building a new relationship of humanity to the rest of the Earth system will come from many other sources besides the cultural-intellectual movements discussed here, notably from science – especially the young discipline of Earth system science. Both the Arts and Sciences need more rather than less societal support to continue creation of ideas and experiences that foster inner personal growth and outer global sustainability.