David P. Turner / February 5, 2024

Figure 1. The Earth at night gives an indication of technosphere energy flow. Image Credit.

The combustion of fossil fuels has powered the rise of humans from hunter/gatherers to planet-orbiting astronauts. Currently, the energy production capacity of Earth’s technosphere (Figure 1) is on the order of 16 TW (see Box 1 or below for background on units). Like Earth’s biosphere (the sum of all living organisms), the technosphere is a dissipative structure and requires energy to maintain itself and grow.

Two big problems with current technosphere energy flow are: 1) most of the energy is generated by combustion of fossil fuels, which release greenhouse gases that are rapidly altering global climate; and 2) the per capita distribution of global energy is highly uneven, with billions of people at the low end of the distribution receiving little to nothing.

The magnitude of technosphere energy flow is not really an issue. Sixteen TW is small compared to the flow of energy associated with biosphere net primary production (on land and in the ocean). The global NPP of around 100 PgC yr-1 is equivalent to about 63 TW of production capacity. Note that the technosphere appropriates close to 25% of global NPP for food and biomass energy. The technosphere and biosphere energy flows are both much smaller than the rate of solar energy reaching the Earth, which is about 1700 TW.

Transitioning away from combustion of fossil fuel to more environmentally benign forms of energy production is feasible, but will be extremely challenging and will take decades. To do so, all sectors of the global economy – notably the transportation sector – must be designed to run on electricity.

A significant constraint to the transformation of the power sector is the slow turnover rate of the fossil fuel infrastructure (e.g. a coal fired power plant will typically last 50 years), which raises the issue of stranded assets if they are retired early. Large reserves of fossil fuels will likely have to be abandoned, unless carbon capture and storage can be economically implemented (so far, a doubtful proposition). Transitioning away from fossil fuels also means cessation of investment in the infrastructure supporting fossil fuel consumption, notably oil and gas pipelines, liquid natural gas (LNG) terminals (for liquification and regasification), and LNG shipping vessels. The neoliberal doctrine about leaving investment decisions to the marketplace does not apply to the renewable energy revolution because fossil fuel users are still externalizing the costs of fossil fuel combustion (i.e. not paying for the impacts of associated climate change). Hence, various subsidies, taxes, and regulations are necessary.

Despite the challenges, the global renewable energy revolution is underway, with rapid deployment of energy technologies such as solar, wind, and geothermal. Nuclear energy is not strictly renewable but can contribute to minimizing carbon emissions. The International Energy Association (IEA) suggests that 2023 was a turning point regarding the magnitude of global investment in renewable energy (spurred on by the Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S.). Employment of technologies such as hydrogen fuel cells, grid scale rechargeable batteries, smart grids, and supersized wind turbines will speed up the transition process. Decentralized energy production (e.g. household solar panels and small power plants) offers many benefits to both developing and developed countries.

With respect to the per capita energy use distribution problem, total energy consumption could stay the same while per capita energy use evened out to a level approximating that in Europe today. However, consumers at the high end of the distribution are resisting reduction in their energy use (such as less air travel). The more likely path to raising consumption at the low end of the distribution will be to increase total energy production. The IEA projects global energy use will increase by 33 to 75 per cent by 2050 (to about 25 TW).

The new energy demand will arise from increased per capita consumption along with an increased global population (topping out at 9-10 billion this century). More energy will be needed to substitute for various ecosystem services that are degraded or broken, e.g. energy to power water desalinization plants. New energy intensive applications like AI are also emerging.

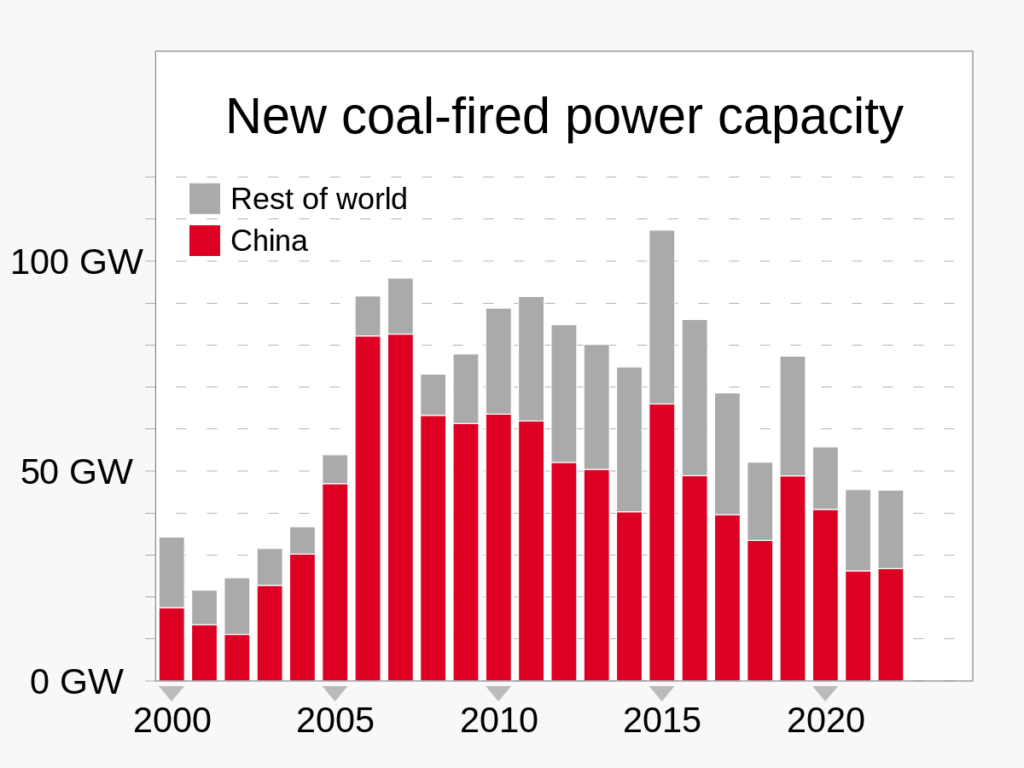

As developing countries build out their local manifestations of the technosphere, it is crucial that the more developed world helps them leapfrog reliance on fossil fuels and go directly to renewable energy sources. In support of that trend, China has announced it will stop funding construction of coal-fired power plants in developing countries (albeit that it continues to build such facilities domestically). The World Bank and IMF have introduced similar policies. Critical political decisions about increased reliance on natural gas in particular are being made now (e.g. in Mexico) and should be strongly informed by the climate change issue.

Getting technosphere energy flow right will require continued technological and political innovation. Success in this communal project will help actualize humanity’s long-term goal to build a sustainable planetary civilization.

Box 1. Background on energy units

________________________________________________________________________

A watt is a unit of energy flow at the rate of 1 joule per second.

One joule is the amount of work done when a force of one newton displaces a mass through a distance of one meter in the direction of that force.

TW = Terra Watt = 1012 Watts = 1,000,000,000,000 Watts.

GigaWatt = 109 Watts = approximate capacity of 1 large coal-fired power plant.

PgC yr-1 = Peta grams of carbon per year = 1015 gC yr-1 = global net primary production in terms of carbon.

The energy equivalence of 1 gC (2 g organic matter) = 36 * 103 J

_________________________________________________________________________