David P. Turner / September 15, 2023

Planting a tree should include a species selection process that factors in projected climate change over the lifetime of the tree. Image Credit.

Equilibrium between vegetation and climate refers to the state in which the species and ecosystem type best adapted to a particular area actually occupy that area.

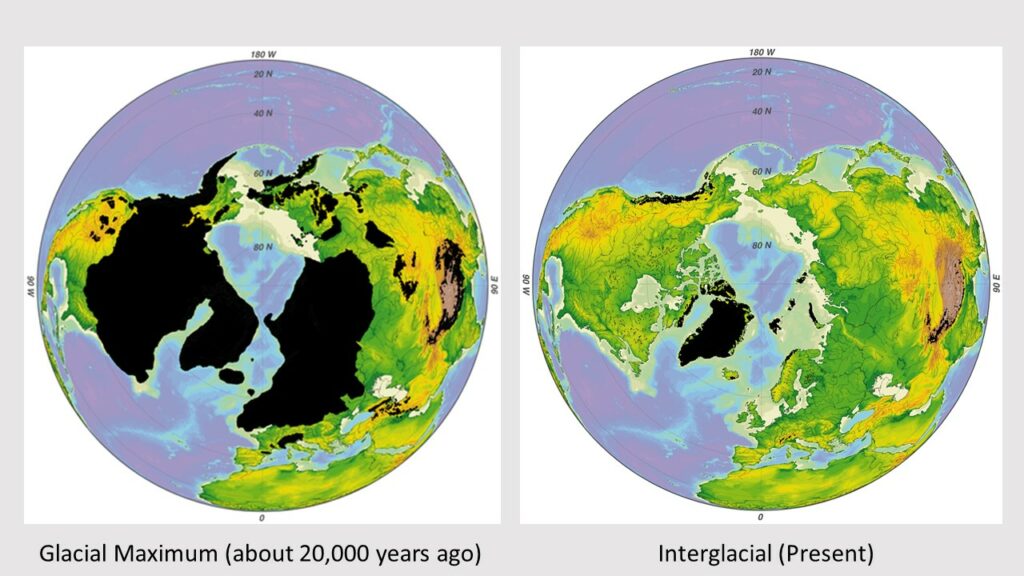

At a geologic time scale, Earth’s climate is always changing and as climate changes, the best adapted species for a given geographical area likewise changes. However, for a variety of reasons, the arrival and establishment of the best adapted vegetation may lag behind the climate change. Biogeographers refer to vegetation/climate disequilibrium in this case.

Note that achieving vegetation/climate equilibrium may take hundreds to thousands of years, so the faster climate is changing, the less likely it is that the vegetation will remain in equilibrium with it.

The Holocene Epoch (from about 11,000 B.P. to present) was characterized by a relatively stable climate, and global vegetation has mostly equilibrated with the climate. But now we have entered the Anthropocene epoch in which anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are driving a high rate of climate warming. Consequently, long-lived vegetation is beginning to fall out of equilibrium with the climate over wide swaths of the terrestrial surface (albeit that humans have already massively altered global vegetation).

As the disequilibrium gets greater, forests in particular become more stressed and vulnerable to disturbances such as insect outbreaks and fire.

The incidence of fire is already increasing around the world because of climate change and we can expect that trend to continue. For example, my simulations of vegetation change in the Willamette Basin (Western USA) project a several fold increase in the incidence of forest fire in coming decades as the climate changes.

The carbon cycle consequences of a growing vegetation/climate disequilibrium are significant.

1. More fires mean more direct emissions of CO2 and more woody residues (dead trees), which will eventually decompose and emit CO2. Local photosynthesis (CO2 uptake) is reduced in recently burned areas until the vegetation leaf area recovers.

2. Forests stressed by climate change are increasingly vulnerable to pests and pathogens. As with fire, associated damage to trees reduces growth and may cause mortality, and the residual dead trees gradually decompose and return CO2 to the atmosphere.

3. Climate change is increasing Vapor Pressure Deficits (the drying power of the atmosphere), which tends to reduce stomatal opening and hence reduce photosynthesis and uptake of CO2. Plant species are adapted to a specific range of VPD and can die when VPDs exceed their tolerance. Interestingly, the increasing concentration of CO2 from fossil fuel emissions compensates to some degree for VPD-induced stomatal closure because CO2 diffusion into the stomata increases as the concentration gradient between leaf exterior and interior rises. The net effect of these opposing factors varies geographically depending on many variables.

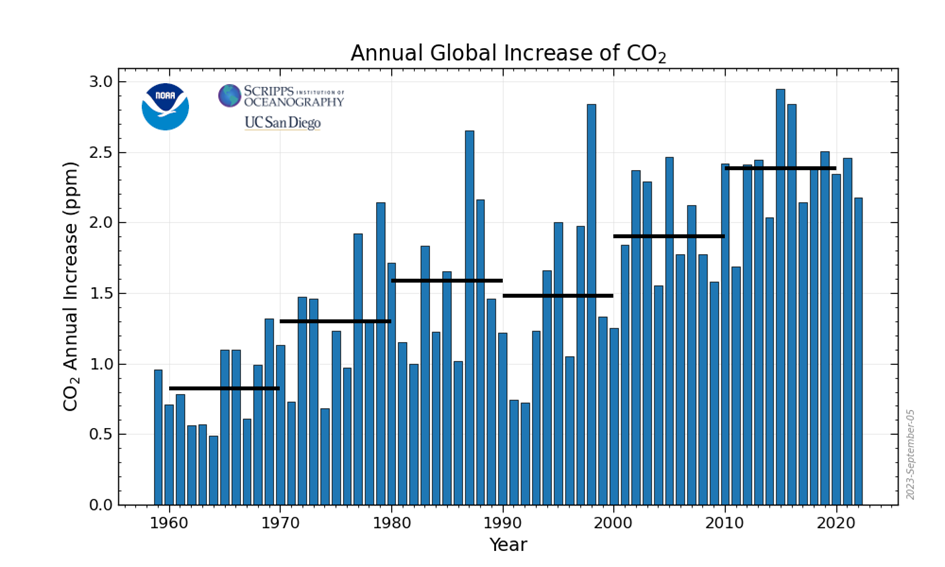

The global impact of increasing disequilibrium between vegetation and climate on the carbon cycle is concerning because it will likely reduce the current terrestrial carbon “sink”. At the global scale, the net effect of biological carbon sources and sinks on land is a carbon uptake equivalent to about 29% of fossil fuel emissions. Much of that carbon accumulation is in wood and soil. The effects of vegetation/climate disequilibrium may reduce the current rate of land-based sequestration, which would leave more fossil fuel-based CO2 emissions in the atmosphere. The annual increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration has increased in recent decades (Figure 1), mostly because of increasing fossil fuel emissions. In the absence of strong emissions reductions, any draw down of the terrestrial sink will tend to further increase that annual uptick in concentration.

Silvaculturalists must have a long planning horizon and some have already begun to factor in vegetation/climate equilibrium in their tree planting prescriptions. They use spatially-explicit projections of climate change from global and regional climate models, along with studies of tree species’ distribution based on historical climate. Given the high certainty of long-term climate change, anyone who plants a tree in the coming decades and centuries ̶ for wood production, climate change mitigation, or various other good reasons ̶ should attempt to account for projected climate change over the lifetime of the tree.

Figure 1. Mean annual carbon dioxide growth rate. Bars are the decadal averages. Image Credit NOAA.