January 20, 2020/David P. Turner

An image of the global biosphere in which depth of greenness on land represents annual photosynthesis. Wikimedia Commons

Natural Processes are Slowing the Accumulation of Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere − Strategic Land Management Could Boost That Trend

As global climate warms in response to rising greenhouse gas concentrations, various components of the Earth system are responding in ways that amplify or suppress the rate of change. Most of these feedbacks are positive (amplify warming). However, a natural negative feedback (suppresses warming) exists and it could be augmented by human actions.

Scientists generally agree that an increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, precipitated by human activities, is a major driver of climate change. Hence, any process induced by rising CO2 and climate change in which less CO2 is added to the atmosphere, or more CO2 is removed from the atmosphere and sequestered, constitutes a negative feedback to climate change.

The most obvious and necessary negative feedback is a rapid reduction in fossil fuel emissions. The 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change points to progress in that direction. Unfortunately, fossil fuel emissions continue to rise.

Research in Earth system science is examining the operation of another significant, but naturally occurring, negative feedback to climate change. Observations suggest that the rising atmospheric CO2 concentration and associated climate change is spurring carbon sequestration by the terrestrial biosphere.

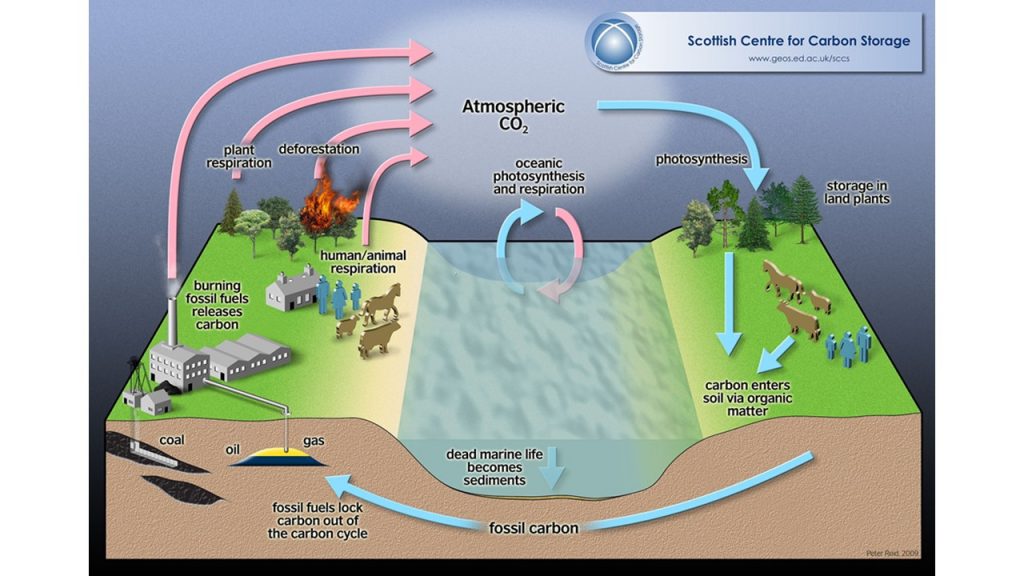

Earth system scientists speak of the “carbon metabolism” of the terrestrial biosphere, referring to the uptake of carbon by way of photosynthesis and its release back to the atmosphere by way of respiration of plants, animals, and microbes (Figure 1). When photosynthesis exceeds respiration, carbon is sequestered from the atmosphere. A critical question concerns the degree to which humanity can purposefully augment this negative feedback and help slow climate change.

Figure 1. The atmospheric CO2 concentration is a function of uptake by processes such as plant photosynthesis, and release by processes such as respiration and combustion of fossil fuels. Wikimedia Commons.

The Terrestrial Biosphere is Speeding Up

Laboratory and chamber studies show that plant photosynthesis is generally sped up, and drought stress is alleviated, as CO2 concentration increases. At the global scale, long-term observations are finding a trend of increasing global photosynthesis in recent decades as the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere rises. The estimated increase is on the order of 30% based on four independent lines of evidence.

Terrestrial respiration (see Figure 1) also appears to be increasing, but at a slower rate. The carbon mass difference between global photosynthesis and respiration is accumulating in the biosphere and helping restrain growth of the atmospheric CO2 concentration.

The dominant reservoir for sequestered carbon is most likely wood. Note that forests accumulate wood as they recover from disturbances. Thus, the terrestrial biosphere uptake or “sink” for carbon is a function of both the disturbance history of global forests and the stimulation of wood production by high CO2.

One indication of an invigorated biosphere comes from observations of the atmospheric CO2 concentration at Mauna Loa Hawaii. The iconic “Keeling curve” (Figure 2) shows an upward trend attributable mostly to fossil fuel emissions, and an annual oscillation, which is attributable to terrestrial biosphere metabolism. The annual drawdown in concentration is driven by an excess of photosynthesis over respiration in the northern hemisphere spring, and observations of CO2 in recent decades find a strengthening of that drawdown. Contributing factors include a longer growing season, deposition of nitrogen from polluted skies (= fertilization), and CO2 stimulation of growth.

Figure 2. Monthly mean atmospheric carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii (in red). The black curve represents the seasonally corrected data. NOAA.

Increasing carbon sequestration by the biosphere is evident from the observation that the proportion of human generated carbon emissions that stays in the atmosphere (the airborne fraction) has fallen in the last decade, despite the large upward trend in fossil fuel emissions. The airborne fraction was 44% for the 2008-2017 period, with the remainder of emissions accumulating on the land (29%) or in the ocean (22%).

Human Augmentation of Terrestrial Biosphere Carbon Sequestration

So, we have a natural brake on the rising CO2 concentration. And it is one that could potentially be augmented by human intention.

Thus far, human land use impacts such as deforestation and agriculture have tended to decrease biosphere carbon storage. However, there is a large potential to deliberately sequester carbon in terrestrial ecosystems by way of several approaches.

1. Expansion of the UN-REDD Programme (United Nations Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation). REDD consists of intergovernmental agreements that pay developing countries to protect forests. The carbon benefit is both in terms of reducing carbon emissions and maintaining carbon sinks. Remote sensing is increasingly effective in monitoring carbon stocks. Norway has begun to make payments to Indonesia for reducing rates of deforestation.

2. Making land management decisions in the context of the whole suite of ecosystem services. Carbon sequestration in biomass and soil is a climate related service that compliments other services such as conservation of biodiversity. Management of both public and private land could be shifted towards this comprehensive perspective.

3. Planting trees − something that can be done at the scale of a suburban back yard, whole urban areas, or regions (Figure 3). Satellite-observed greening in China is attributed in part to large scale tree planting. Trees affect the absorption and reflection of solar radiation as well as the carbon balance, so care must be taken about planning large scale plantings.

Figure 3. Forests accumulate large stocks of carbon relative to other vegetation cover types. Wikimedia Commons.

These human-mediated carbon sinks will all benefit from high CO2 impacts on biosphere metabolism. In contrast, the impacts of continuing climate change − independent of CO2 impacts − on these carbon sinks and on biosphere metabolism generally are difficult to anticipate. At high latitudes, climate warming appears to be associated with vegetation greening. In contrast, increased rates of disturbance in mid-latitudes − such as climate warming induced forest fire − may offset the strength of biosphere carbon sequestration.

In an optimistic scenario, radically reduced fossil fuel emissions along with increased carbon uptake by the land and ocean will cause the atmospheric CO2 concentration to peak within this century, leading to a gradual decline that is powered by biosphere sequestration (natural and augmented).

Since we are already committed to significant climate change, that CO2 trajectory would still leave us with major − but hopefully manageable − adaptation challenges. A stabilized CO2 concentration, would also reduce the possibility that the Earth system will cascade through of series of positive feedback tipping points. That scenario would take hundreds to thousands of years to play out but it could push Earth into a state threatening to even a well-organized, high-technology, global civilization.

David,

I heard about this site while FaceTiming with my wife, Marianne, her brother Art and your sister, Barbara. Previously, I had read your impressive book.

Regarding sequestration, I have a question that Marianne and I have discussed for many years. We own a farm in Maine that includes 30 acres of wild low bush blueberries, 50 acres of open fields and 130 acres of forest. We mow half of the open fields once a year in October. That strategy has promoted wild native pollinators allowing us to rent a third of the honeybee hives that are normally used during the blueberry blossom season and leading to much higher rate of pollination. Wild bees are out during any weather, unlike honeybees. Mowing in October also protects Monarchs as there is a lot of milkweed in the fields.

So, we’ve pondered planting good carbon sequestration trees such as red oak in the fields, which now only have about 30 apple and pear trees. While Maine has warmed more than any state in the country but Alaska, there is still snow cover most of the winter. So, planting trees in those fields would eventually eliminate albedo from from snow covered or even somewhat reflective dry grasses. So, do you think that the carbon sequestering trees planted in those fields would provide climate benefit beyond the loss of albedo? Of course, by the time those trees are large enough to provide significant sequestration, there will be little or no snow cover.

Thanks for your great work on the climate monster.

Tony

Thanks for your positive comments about The Green Marble. That whole issue about energy balance aspects of tree planting in northern forest is still controversial. In your situation I’m thinking that in the long run the carbon sequestration benefits would outweigh the energy balance costs associated with reducing snow albedo. Deciduous trees might be better than conifers because they would not block the winter snow reflectance as much.