David P. Turner / March 7, 2021

The developmental task of building a personal identity is becoming ever more complicated. While some aspects of identity come with birth, others are adopted over the course of maturation. Increasingly, each person has multiple identities that are managed in a complex psychological juggling act.

Citizenship − generally defined in terms of loyalty to the society within a specified area − is a key component of personal identity. National citizenship most readily comes to mind, but the term is also used at other levels of organization. Members of a tribe, residents concerned about watershed protection, and neighbors attending to local quality of life all qualify as citizens.

The concept of citizenship at the planetary scale is rather new, in part because our global governance infrastructure (environmental, geopolitical, and economic) is rudimentary. However, if there is to be a purposeful (teleological) attempt to mitigate and adapt to global environmental change, we residents of Earth must become planetary citizens.

The impetus to identify as a planetary citizen typically comes from growing awareness of planetary scale environmental threats to human welfare. The result is a commitment to rein in the human enterprise (the technosphere) and work towards global sustainability.

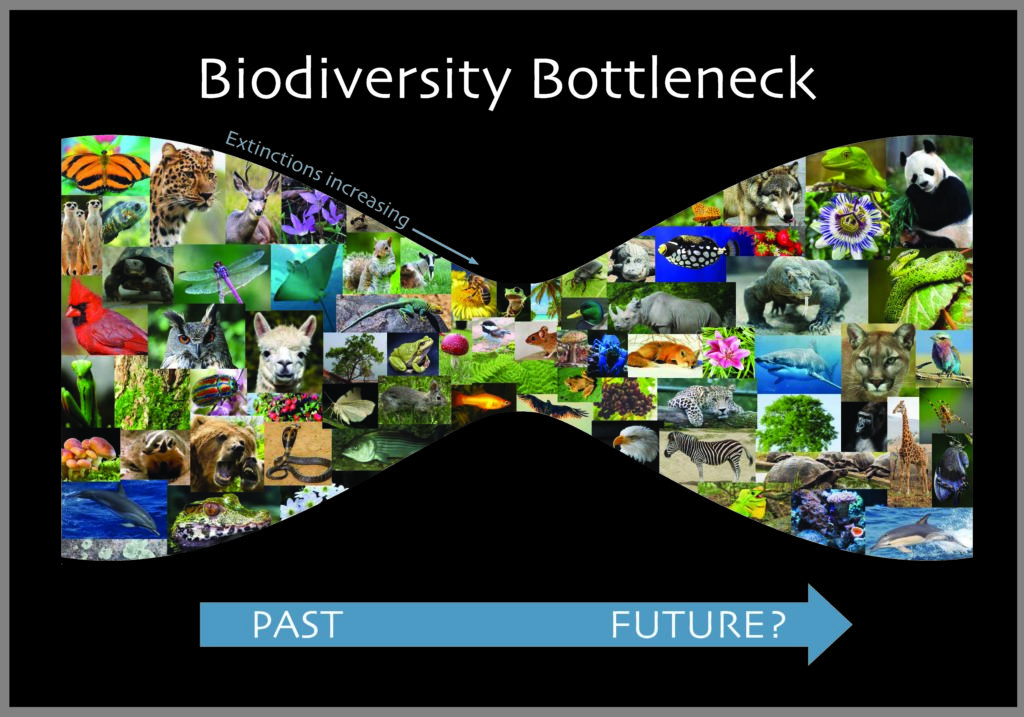

Earth system scientists generally reject the Gaian notion that the planet is in some way self-regulating or purposeful. But if humanity indeed manages to join together and intentionally reverse the trend of rising greenhouse gas concentrations and mass extinction, the Earth system as a whole (Gaia 2.0) would in a sense gain purpose.

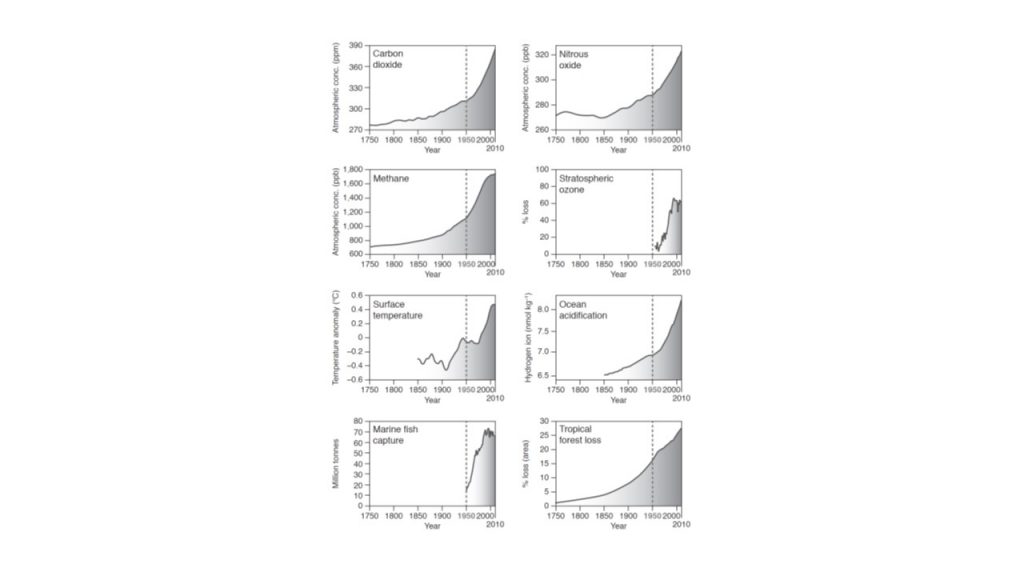

Embrace of planetary citizenship is a pushback against unbridled individualism. In the widely held neoliberal belief system, individuals are viewed most fundamentally as autonomous consumers who live in a biophysical environment that is a limitless source of materials and energy as well as a limitless sink for wastes. In fact, the human impact on the global environment is a summation of the resource demands from the 7.8 billion people who now inhabit the planet. The cumulative impact of humanity has clearly begun to induce changes in the Earth system that endanger both developing and developed nations.

Rights and Responsibilities

Planetary citizens have rights, in principle. As noted though, the global governance forums for establishing those rights are weak. In the realm of environmental quality, a planetary citizen certainly should have a right to an unpolluted environment.

Correspondingly, a planetary citizen’s responsibilities include understanding their own resource use footprint, and endeavoring to control it (e.g., having fewer children). Understanding the environmental impacts of their society and advocating in support of conservation-oriented governmental policies and actions (e.g., by voting) is also essential.

Because global change is happening so quickly and persistently, a commitment to lifelong learning about local and global environmental change is a foundation of planetary citizenship.

Identifying with any collective evokes a tension between personal autonomy and obligations to the greater good. Thus, the addition of planetary citizenship to personal identity creates psychological demands. Mental health requires that those new demands (e.g., pressure for less consumerism and more altruism) be calibrated to individual circumstances and to the state of the world.

Collective Intelligence

Possibilities for the emergence of collective intelligence and agency among planetary citizens at various scales have grown rapidly as the Internet has evolved. Besides the general sense of a global brain emerging from the mass of online communication, various online groups now specifically address global environmental change issues, e.g. the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence sponsors a crowdsourced web site aimed at finding solutions to climate change.

Civil society organizations like 350.org, Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere, and Wikipedia are testaments to the power of collective intelligence among planetary citizens. Participation of planetary citizens in self-organized groups of activists creates a sense of agency, which can be hard to find when a person confronts the enormity of global environmental change on their own. What is glaringly missing is a planetary forum for global environmental governance, something like the proposed World Environment Organization.

Global Citizenship

It is worth making a distinction between planetary citizenship and global citizenship. Both concepts are relevant to building global sustainability, with planetary citizenship more focused on the biophysical environment and global citizenship more concerned with human relationships. The global perspective is fundamentally political.

Global Citizenship is often discussed in the context of Global Citizenship Education (GCE). GEC theory commonly calls for “recognizing the interconnectedness of life, respecting cultural diversity and human rights, advocating global social justice, empathizing with suffering people around the world, seeing the world as others see it and feeling a sense of moral responsibility for planet Earth”.

Traditional GCE theory may be oriented around experiential learning by way of immersive experiences in other cultures, often including volunteer work. However, persistent concerns that the relationship of visitor to host replicates the colonial model of dominance have led to more critically oriented versions of GCE theory. Here, the emphasis is on examining injustices and power differentials among social groups and evaluating effective means to foster greater equity.

The thrust of the global citizenship concept tends towards differentiating the parts of humanity and fulfilling the obligation to address injustices of all kinds; the thrust of planetary citizenship is on humanity as a collective entity playing a role in Earth system dynamics. A comprehensive approach to teaching global citizenship would emphasize both aspects and even transcend them.

Pedagogy

Since identity as a planetary citizen is a choice, the question of how education can be designed to foster that choice is significant.

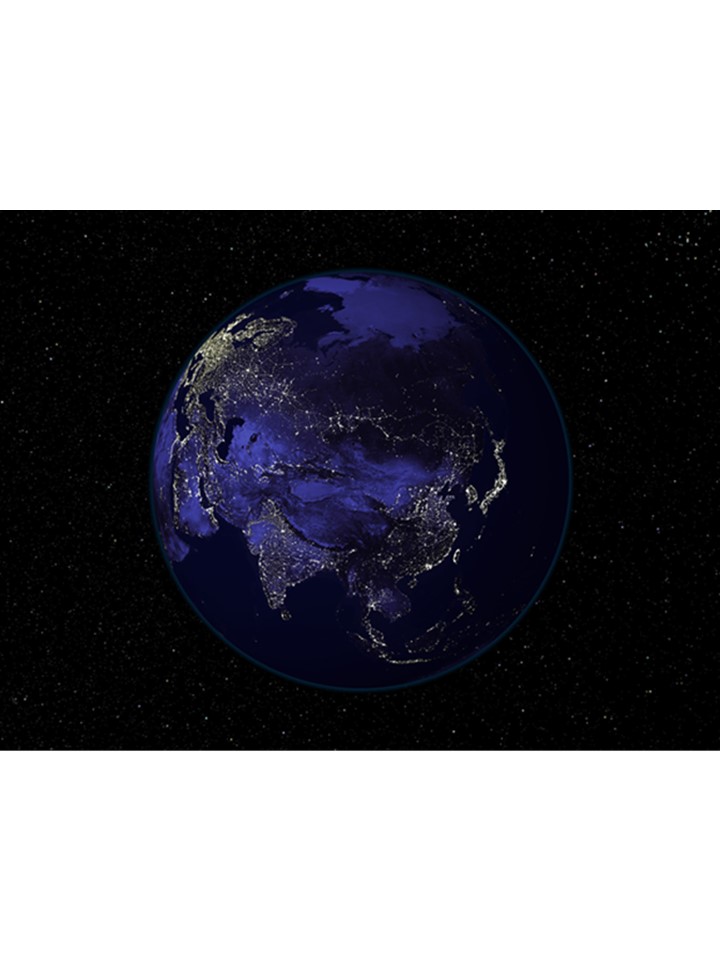

The idealized outcome of education for planetary citizenship is a human being who understands the impacts of the technosphere on the Earth system and has a willingness to engage in building global sustainability (Go Greta Thunberg!). These individuals would share a sense of all humans having a common destiny.

Two disciplines are particularly relevant.

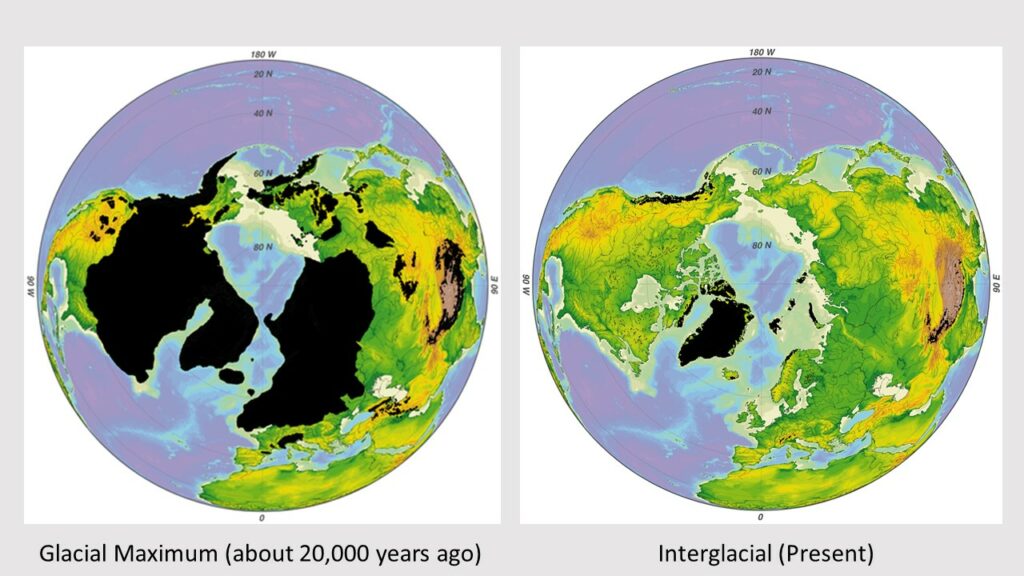

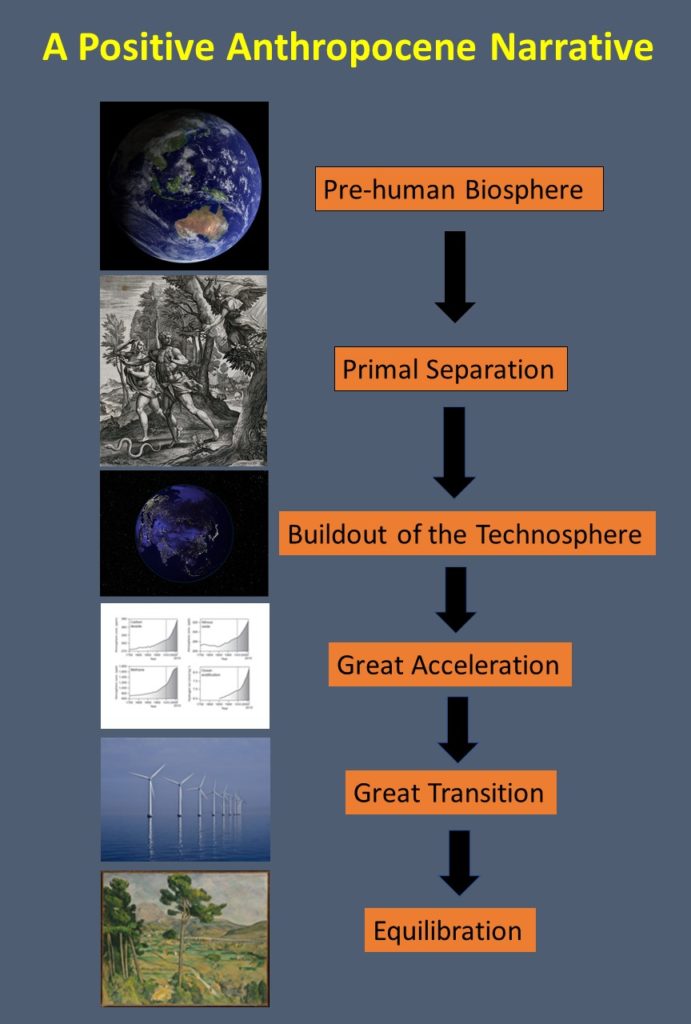

The field of Big History covers the history of the universe leading to the current Earth system. It juxtaposes cosmic evolution, biological evolution, and cultural evolution to give perspective on how humanity has become aware of itself and come to endanger itself. A recently developed free online course in Big History aimed at middle school and high school students nicely introduces the subject. My own text, The Green Marble, and my blog posts such as A Positive Narrative for the Anthropocene, examine Big History at a level suitable for undergraduate and graduate students.

The field of environmental sociology is likewise important. It explores interactions of social systems with ecosystems at multiple spatial scales. The concept of a socioecological system, composed of a specific ecosystem and all the relevant stakeholders, is a core object of study. Nobel prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom helped elucidate the optimal structural and functional properties of socioecological systems at various scales.

Conclusion

Identifying as a planetary citizen means seeking to understand humanity’s environmental predicament and trying to do something about it. An important benefit from this commitment is the acquisition of a sense of agency regarding global environmental change. The aggregate effect of planetary citizenship across multiple levels of organization (individual, civil society, nation, global) will be purposeful change at the planetary scale.