Awe – A Shared Uncommon Human Experience

Can you recall the last time you experienced awe? It is likely you can because awe is an emotion that tends to be a positive memorable experience. What were you doing during your awe experience? Did you learn anything from it? Do you still think about it? This post will profile the nature of awe and will conceptualize how we may integrate awe in learning design for online instruction. We will begin with exploring what awe is and how it occurs. Then our focus will turn to how awe might impact cognition and therefore learning. Lastly some examples of how awe integration might be conceptualized for online instruction and remote experiential learning.

It is understood that awe is a common feeling associated with experiencing art, music, panoramic views, and other beauty (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). Awe is considered a positive emotion with a prototypical facial display (Shiota, Campos, and Keltner, 2003). Awe is a state experience that is differentiated from other positive emotions such as amusement, interest, love, joy, contentment, and pride (Campos et al., 2013). As an emotional state it is transient but may produce feelings of transformation, or openness, due to its impact on cognition (Danvers & Shiota, 2017). Course developers and instructional designers often value new ways of creating learning experiences in course design. The nature of awe suggests it may be useful in that regard. Before we can integrate awe into online course design we must have a better understanding of how it occurs.

What Makes Awe Happen?

The awe experience is elicited by two key features in a stimulus: perceptual vastness and need for acommodation (Shiota & Keltner, 2007). Although perceptual vastness is often experienced when viewing grand landscapes, vastness may also be found in any stimulus that expands a person’s accustomed frame of reference.

From this perspective vastness may be understood as a function of space, time, number, complexity, ability, or the mass of human experience. Shiota and Keltner (2007) further suggest vastness may be implied by a stimulus, making even a mathematic equation feel vast due to its ability to explain a large number of phenomena. Even people like Henry Ford, Rachel Carson, Queen Elizabeth II, Nelson Mandela, and Bill Gates might elicit a sense of vastness due to their understood expansive impact on the lives of others and society.

When facing this sense of vastness that challenges personal understanding, we adapt. Cognitive accommodation is a process of changing our thinking patterns, or frames of reference, in the face of perceptually vast stimuli. This differs from assimilation which brings a new experience in line with existing schemas or experiences. In contrast, accommodation stimuli reshape or alter existing cognitive schema. This sense of a need for accommodation is the second key feature of the stimuli that elicit awe.

How Awe Impacts Us

From a cognitive perspective awe occurs during the engagement with novel, complex, patterned information that is accessible yet, as previously has been stated, is outside a normal understanding of the world (Keltner & Haidt, 1999). This cognitive challenge creates a feeling of wonder and astonishment and humans respond (Shiota et al., 2017). Rather than depend on default cognitive frames of references or scripts, awe encourages cognitive accommodation, prompting the taking in of new information to update understanding.

The accommodation process fostered by awe focuses a more detailed analysis of the information-rich stimulus under consideration. In this process individuals in awe shift their awareness away from normal concerns. In a sense, awe changes our vantage point to something greater than ourselves and opens the mind to new information, perspectives, and understandings.

Awe not only leads to new ways of processing information it also changes how we see the world, making life a richer experience. Research has shown that awe elicits self- relevant thoughts and connectedness leading to an experience of a “small self” (Nelson-Coffey et al., 2019). These self-transcendent feelings are positive and contribute to awe being an emotion that is pleasant and calming and inspires an interest in social responsibility.

Integrating Awe in Online Instruction

After an awe experience it is likely we have changed our thinking, feeling, and perhaps behaivor. Isn’t this one of the great purposes of education and a goal of learning? How might we leverage this awe in online instruction?

A recent op-ed by Goldie Blumenstyk in The Chronicle of Higher Education (2020) addressed the topic of what kind of higher education is needed now and beyond the current pandemic. Blumenstyk identified a number of issues. Two are salient to a discussion of integrating awe into online learning. In brief these were:

- A need for more applied learning that can be evaluated through guided reflection and mentoring to prepare students for careers of purpose in society.

- Customized education, leveraging the online environment and technology that is both values-based and experiential.

As we have seen in the research, awe theory addresses the needs identified by Blumenstyk. Awe is a positive emotional experience that fosters personal reflection. It is individualistic, or personally customized, and inspires consideration of ideas and actions outside the self and increases prosocial behavior (Piff et al, 2015). It is clearly experiential in nature. Awe as a goal and vehicle for learning seems worth exploring. How might we integrate awe into course design and development of online instruction. Let’s look at three different examples as a starting point.

Example #1: Referencing Awe Experiences in Learning

One of the most obvious and perhaps easiest way to bring awe into online instruction is to have learners reference past awe experiences as part of their course work. This may seem daunting to faculty who cannot identify or manage what experiences will be brought forward. However, that is part of the benefit. Referencing awe experiences is a personal application of learned experience to the online environment. As an example, an instructor may post a discussion prompt that might look like this.

Discussion Prompt – Topic: Poverty and the Social Safety Net

For this assignment I would like you to recall a time you experienced awe. Where were you? How did you feel in that moment of awe? Did it change your perspective in any way? Once you have thought about your awe experience post a response to the following questions:What ideas or feelings about your role in society are related to your awe experience? Are your beliefs about poverty and the role of government in providing a social safety net informed by your perceived role in society? How is your perspective aligned with government policies concerning social aide?

Although not completely fleshed out in terms of response posts or a rubric this discussion prompt encourages individualized learning related to the course topic of poverty in the local community. It encourages reflection, analysis, and logical comparison. It brings awe into the discussion as an individualized reflective element.

Example #2: Stimulate Awe Experiences in Learning

Research on awe has used writing about awe and video viewing to stimulate awe in study subjects. Stimuli that creates a sense of perceptual vastness and accommodation shapes the awe emotional response. Can we create these opportunities for students? Below is an example to consider.

Interactive Timeline – Topic: Anthropology and Early Human Migration

At Oregon State University we often use a proprietary timeline tool in online courses. The scale of this timeline can be varied and it typically is media enriched with images, video, text, and links. Any timeline can be built entirely by the instructor or students can contribute to the timeline as part of an assignment.

In this example of a senior level Anthropology course the instructor provides a timeline chronicling physical appearance of the Bering Land Bridge and the migration of humans across the land bridge into North America. The assignment may read something like what is seen below:

Paper Assignment Prompt

For this assignment review the contents of the Bering Land Bridge timeline that addresses the migration of humans in the Beringia region during the Ice Age. In your review pay close attention to the process of glaciation and how it impacts both the land bridge and human and animal migration patterns. Note the length of this time period.

Once your review is complete write a paper about Beringia and the scale of both the time period and human/animal migration. What impressed you about the history and geography of the migration? How does this migration inform your thinking about how species adapt to survive?

Although a cursory assignment, it illustrates an intent to engage students with the vastness of geology and geography and immense physical/cultural change over time. It also asks learners to reflect on new information and how it may inform current thinking about the human experience and nature. It is designed with an awe experience in mind. And it is presented and completed entirely online.

Example #3: Awe In Experiential Learning – Art Appreciation

In an earlier post on this site Rademacher (2019) described the process of experiential learning. That process is depicted in the experiential learning model below (Kolb & Kolb, 2018).

The starting point of the experiential learning process is the concrete experience. Incorporating awe into experiential learning is about designing learning that integrates an awe eliciting concrete experience. Once that is complete, then the experiential learning cycle can be completed. Interestingly, the four stages of the experiential learning cycle seem to parallel the awe experience process. In the table below, you can see the parallels that might be conceptualized. This teases the idea that awe may be an archetype of experiential learning.

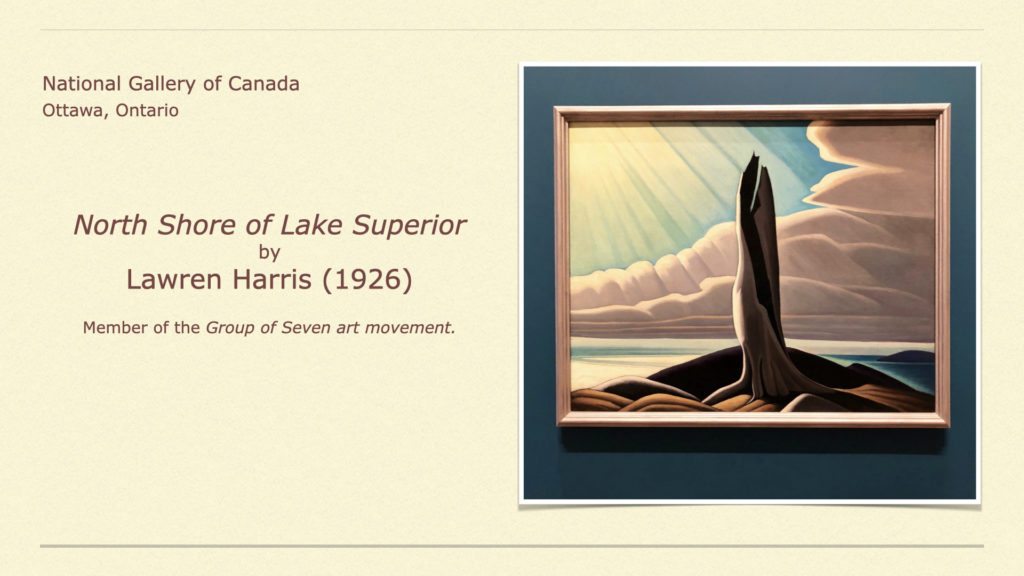

So in this example the goal is to create a remote learning experience where students seek out a setting where they may, or have, experienced awe. As various forms of art elicit awe let’s use an art example.

Experiential Learning Assignment Description

The major assignment for this term is to examine the purpose of art in the human experience. Your assignment is to visit a local art gallery or museum of your choice. During your visit identify several art pieces that you feel inspired by. Spend focused time looking over and reading about your favorite piece of art. If permitted, take a photograph of that piece of art for future reference.

Compose a paper about your art experience. Before you write, reflect on how the artwork you photographed inspired you. With that in mind provide answers to the following questions:

- Describe your thoughts and feelings about experiencing the artwork in person?

- Did your understanding of art change from this experience? How?

- How might you approach viewing art differently in the future?

- How do you think your experience might be like that of other people viewing this art?

- Describe how your art experience affirms or contrasts the purpose of art as defined by the authors of the course text.

Submit your paper via the learning management system by…

These three examples were provided as a way to begin thinking about how we might integrate awe as part of online instruction. Each example is incomplete and would need further details. Each does, however, provide a kernel of an idea of how awe integration might be pursued.

Final Thoughts

Awe is a common human emotion that has been shown to be important from the perspectives of spirituality, philosophy, health, wellness, and defining ourselves (Keltner, 2016; TED, 2016). This article posits that awe may also be valuable as a vehicle for online instruction and learning. As course designers we often look for ways to connect real life experience with the online learning environments. The conceptual parallels between awe and the experiential learning cycle highlighted earlier may be worth examining in greater depth.

In her 2016 TED Talk, awe researcher Lani Shiota defined awe:

Awe is an emotional response to physically or conceptually extraordinary stimuli that challenge our normal frame of reference and are not already integrated in our understanding of the world.

Shiota’s definition suggests that awe serves as a form of new learning originating from things we do not readily understand. Yet it is not simply taking in new knowledge, it is adapting to ideas and physical stimuli that we perceived as vastly bigger than our selves. It may prove valuable for course developers and designers to think about what awe opportunities might exist in the design of online instruction. We might begin that process by better understanding how awe shapes cognition and emotion. Integrating awe into online instruction could very well help online learners find the vastness and beauty of new subjects, new ideas, or new experiences.

References

Blumenstyk, G. (2020, April, 22). The higher ed we need now. Leadership & Governance | The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Higher-Ed-We-Need-Now/248591

Campos, B., Shiota, M.N., Keltner, D., Gonzaga, G.C., & Goetz, J.L. (2013) What is shared, what is different? Core relational themes and expressive displays of eight positive emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 27 (1), 37-52.

Danvers, A.F. & Shiota, M.N. (2017). Going off script: Effects of awe on memory for script-typical and irrelevant narrative detail. Emotion, 17 (6), 938-952.

Keltner, D. (2016, May 10). Why do we feel awe?. Greater Good Magazine.

Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/why_do_we_feel_awe

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (1999). The social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 505–522.

Keltner, D. & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17 (2), 297-314.

Kolb, A. & Kolb, D. (2018). Eight important things to know about The Experience Learning Cycle. Australian Educational Leader, 40 (3), 8-14.

Nelson-Coffey, S.K., Ruberton, P.M., Chancellor, J. Cornick, J.E. & Lyubomirsky, J. (2019). The proximal experience of awe. Public Library of Science (PLoS One), 14 (5), p. e0216780.

Piff, P.K., Dietz, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D.M., & Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883-889.

Rademacher, C. (2019, February 16). Experiential learning in online instruction. Ecampus Course Development & Training (Oregon State University). Retrieved from http://blogs.oregonstate.edu/inspire/2019/02/06/experiential-learning-in-online-instruction/

Shiota, M.N., Campos, B., and Keltner, D. (2003). The faces of positive emotion: Prototype displays of awe, amusement, and price. Annals New York Academy of Science, 1000, 296-299.

Shiota, M.N. & Keltner, D. (2007). The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion 21 (5), 944-963.

Shiota, M.N., Thrash, T.M., Danvers, A.F., & Dombrowski, J.T. (2017). Transcending the self: Awe, elevation, and inspiration. In M. Tugade, M. N. Shiota & L. Kirby (Eds.), Handbook of positive emotion (pp. 362–395). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

TED (2016). Why awe is such an important emotion | Dacher Keltner [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysAJQycTw-0

TED (2016). Why awe is such an important emotion | Lani Shiota [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uW8h3JIMmVQ

For DIY video production, there are many ways to go about this!

For DIY video production, there are many ways to go about this!