Memory plays the central role in learning – it is “the mechanism by which our teaching literally changes students’ minds and brains” (Miller, 2014, p. 88). Thus, understanding how memory works is important for both instructional designers and instructors. According to modern theories, memory involves three major processes: encoding (transforming information into memory representations), storage (the maintenance of these representations for a long time), and retrieval (the process of accessing the stored representations when we need them for some goal or task) (Miller, 2014). Let’s briefly review these processes and see how they may inform our course design and instruction.

Encoding – What Is the Role of Attention and Working Memory?

How does encoding happen? We receive information from our senses (visual, auditory, etc.), and then we perform a preconscious analysis to check whether it is important to survival and if it is related to our current goals. If it is, this information is retained and will be further processed and turned into mental representations. Thus, attention is the major process through which information enters our consciousness (MacKay, 1987). Attention is limited, and it is to some extent under voluntary control, but it can be easily disrupted by strong stimuli. Attention is crucial for memory, and without attention we cannot remember much (Miller, 2014).

How attention is directed depends on the way the content is presented and on the nature of the content itself (Richey et al., 2011). If the content is intrinsically motivating for the student, it will catch their attention more readily. But beyond that, the manner we design our instructional materials can influence how learners focus their attention to select and process the information, and in turn on what and how much gets stored in their memory. For example, we can ensure that students are guided to the most relevant content first by making that content more visually salient. Or we can tell an engaging story to focus their attention to the concepts that come next.

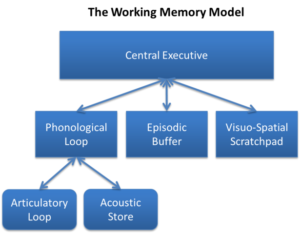

Working memory is a concept introduced in the 1970s by Alan Baddeley. This model describes immediate memory as a system of subcomponents, each of them processing specialized information such as sounds and visual-spatial information. This system also performs operations on this information and are managed by a mechanism called the central executive. The central executive combines the information from the various subcomponents, draws on information stored in long-term memory, and integrates new information with the old one (Baddeley, 1986).

Some researchers consider attention and working memory to be the same thing; while not everyone agrees, it is clear that they are highly interconnected and overlapping processes (Cowan, 2011; Engle, 2002). Attention is the process that decides what information stays in working memory and keeps it available for the current task. It is also involved in coordinating the working memory components and allocating resources based on needs and goals (Miller, 2014).

The capacity of each of the working memory components is limited. However, these components are mostly independent: visual information will interfere with other visual information, but not much with another type such as verbal information (Baddeley, 1986). Therefore, the most effective instructional materials will include a combination of media, such as images and text (or better yet, audio narration), rather than just images or just text.

Graphic by Cheese360 at English Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Storage – How Fast Do We Forget?

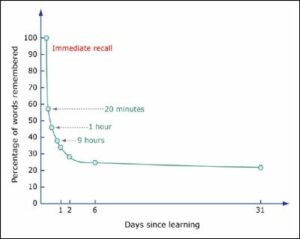

In the late 1800s, Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted his famous series of experiments on the shape of forgetting. The result was the forgetting curve (also called the retention curve), which is a function showing that the majority of forgetting takes place soon after learning, after which less information will be lost (Ebbinghaus, 1885). A recent review of studies on the retention curve concluded that the rate of forgetting may increase up to seven days, and slows down afterwards (Fisher & Radvansky, 2018). This interval is useful to consider when planning instruction. A well-designed course will include sufficient opportunities for practice and retrieval during this time, so as to minimize the forgetting that naturally occurs.

Graphic from MIT OpenCourseWare is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Retrieval – How Do We Get It Out of Our Heads and Use It?

While long-term memory is considered unlimited, retrieval (or recall) can be challenging. Its success depends on a few factors. To retrieve memory representations, we use cues—information that serves as a starting point. Since a memory can include different sensory aspects, information with rich sensory associations is usually remembered more easily (Miller, 2014). Visual and spatial cues are particularly powerful: memory athletes perform some mind-blowing feats by using a special technique called “the memory palace”—imagining a familiar building or town and placing all content inside it in visual form (to learn more about this technique, check out this TED talk by science writer Joshua Foer).

Recall is also influenced by how the information was first processed: deep processing (focusing on meaning) will yield superior retrieval performance compared to shallow processing (focusing on superficial features like some key words or the layout of the information). However, equally important is a match between the type of processing that happens during encoding and the one that happens during retrieval (Miller, 2014). For instance, if the final exam contains multiple-choice questions, learners will perform better if they also practiced with multiple-choice questions when they learn the content. Finally, emotions have been shown to boost memory (Kensinger, 2009), and even negative emotions (such as fear or anger) can have a strong effect on recall (Porter & Peace, 2007).

Conclusion – Implications for Instruction

What can we do to maximize our students’ memory potential? Based on these memory characteristics, here are a few strategies that can help:

- Make use of graphic design and multimedia learning principles to create attention-grabbing, well-organized instructional materials that include a combination of media.

- Include plenty of retrieval practice activities, such as polling during lectures, quizzes, or flashcards. The website Retrieval Practice is a fantastic resource for quick tips, detailed guides, and research. Top things to keep in mind:

- Boost retrieval practice through spacing (spreading sessions over time) and interleaving (mixing up related topics during a practice session).

- Make sure you plan some sessions for the critical seven-day period after introducing the material.

- Consider teaching students the memory palace technique for content that requires heavy memorization.

- Support every type of content visually where possible.

- Encourage deep processing of the material, for example through reflections, problem-solving, or creative activities.

- Ensure that students have opportunities to engage with the material during learning in the same way as they will during the exam.

- Try to stimulate emotions in relation to the content. While negative affect can help (for example, recounting a sad story to illustrate a concept), it is probably best to focus on positive emotions through exciting news, inspiring anecdotes, and even more “extrinsic” factors such as humor, uplifting music, or attractive visual design.

Using these strategies will help you create learning experiences where students encode, store, and retrieve information efficiently, allowing them to use it effectively in their lives, studies, and work. Do you have any related experience or tips? If so, share in a comment!

References

Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Working memory. Oxford University Press.

Cowan, N. (2011). The focus of attention as observed in visual working memory tasks: Making sense of competing claims. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1401–1406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.035

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology.

Engle, R. W. (2002). Working memory capacity as executive attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00160

Fisher, J. S., & Radvansky, G. A. (2018). Patterns of forgetting. Journal of Memory and Language, 102, 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2018.05.008

Kensinger, E. A. (2009). How emotion affects older adults’ memories for event details. Memory, 17(2), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802221425

MacKay, D. G. (1987). The organization of perception and action: A theory for language and other cognitive skills. Springer New York. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4754-8

Miller, M. D. (2014). Minds online: Teaching effectively with technology. Harvard University Press.

Porter, S., & Peace, K. A. (2007). The scars of memory. Psychological Science, 18(5), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01918.x

Richey, R., Klein, J. D., & Tracey, M. W. (2011). The instructional design knowledge base: Theory, research, and practice. Routledge.