For those of us who consume dairy products, we often don’t give much thought to the trials and tribulations that had to be faced to get that product on the grocery shelves. It’s probably a fair assumption to say that most of us have never considered that cheese could explode, but that is the center of Madeleine Enriquez’s graduate research.

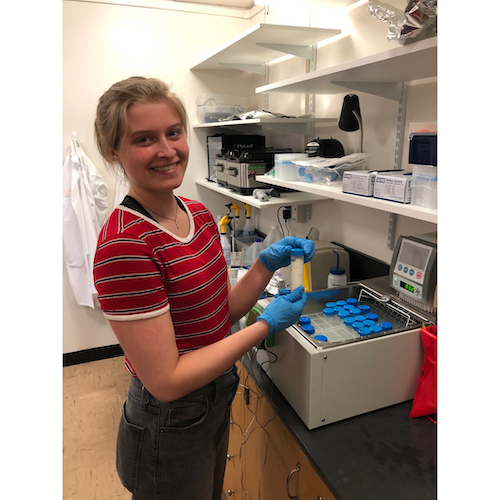

Madeleine (Maddie) is a master’s student in the laboratory of Joy Waite-Cusic, and she investigates dairy microbiology and spoilage, particularly mitigating “gas defects” in cheese. In semi-hard to hard cheeses certain microorganisms can cause build-up of gasses called “gas defects” which can eventually lead to blow-outs of the cheese in its packaging, or significant structural defects within the cheese (think Swiss cheese holes where they’re not supposed to be). Maddie works on practical and easy ways to mitigate these gas defects for small dairy farmers. Some of the variables include aging temperature, bioprotective cultures, or combinations of both.

Maddie’s interest in this particular area of food science originally stemmed from her grandfather, who was a dairy farmer. She went to the University of Connecticut for her bachelor’s degree in animal science. While there she participated in undergraduate research on dairy farms, particularly focusing on dairy microbiology later in her degree. This eventually led to her coming to Oregon State to further her education in dairy food science.

If you want to hear more about exploding cheese, making gouda on a weekly basis, and strapping wheels of cheese in for a CT scan, tune in for this episode of ID airing live on Jan 21, 2024.