Core Education at Oregon State University launched summer 2025 and is designed to deepen how students think about problem-solving in ways that transcend disciplinary-specific approaches. It aims at preparing students to be adaptive, proactive members of society who are ready to take on any challenge, solve any problem, advance in their chosen career and help build a better world (Oregon State University Core Education, 2025).

Designing Seeking Solutions Signature Core category courses presents a few challenges, such as the nature of wicked problems, cross-discipline teamwork, and the global impact of wicked problems, to name just a few. In the past eight months, instructional designers at Oregon State University Ecampus have worked intensively to identify design challenges, brainstorm course design approaches, discuss research on teamwork and related topics, and draft guidelines and recommendations in preparation for the upcoming Seeking Solutions course development projects. Here is a list of the key topics we reviewed in the past few months.

1. Wick Problems

2. Team conflict

3. Online Large Enrollment Courses

Next, I will share summaries of research articles reviewed and implications for instructional design work for each of the above topics.

Wicked Problems

A wicked problem, also knowns as ill-structure problem or grand challenge, is a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve due to its complex and ever-changing nature. Research suggests that wicked problems must have high levels of three dimensions: complexity, uncertainty and value divergence. Complexity can take many forms but often involves the need for interdisciplinary reasoning and systems with multiple interacting variables. Uncertainty typically refers to how difficult it is to predict the outcome of attempts to address wicked problems. Value divergence refers particularly to wicked problems having stakeholders with fundamentally incompatible worldviews. It is the presence of multiple stakeholders in wicked problems with incompatible viewpoints that marks the shift from complex to super complex. (Veltman, Van Keulen, and Voogt, 2019; Head, 2008)

The Seeking Solutions courses expect students to “wrestle with complex, multifaceted problems, and work to solve them and/or evaluate potential solutions from multiple points of view”. Supporting student learning using wicked problems involves designing activities with core elements that reflect the messiness of these types of problems. McCune et al. (2023) from University of Edinburgh interviewed 35 instructors teaching courses covering a broad range of subject areas. 20 instructors teaching practices focused on wicked problems, while the other 15 instructors whose teaching did not relate to wicked problems. The research goal is to understand how higher education teachers prepare students to engage with “wicked problems”—complex, ill-defined issues like climate change and inequality with unpredictable consequences. The research question is “Which ways of thinking and practicing foster effective student learning about wicked problems?” The article recommended four core learning aspects essential for addressing wicked problems from their study:

1. Interdisciplinary negotiation: Students must navigate and integrate different disciplinary epistemologies and values.

2. Embracing complexity/messiness: Recognizing uncertainty and non linear problem boundaries as part of authentic learning.

3. Engaging diverse perspectives: Working with multiple stakeholders and value systems to develop consensus-building capacities.

4. Developing “ways of being”: Cultivating positional flexibility, uncertainty tolerance, ethical awareness, and communication across differences

Applications for instructional designers:

As instructional designers work very closely with course developers, instructors, and faculty, they contribute significantly to the design of Seeking Solutions courses. Here are a few instructional design recommendations regarding wicked problems from instructional designers on our team:

• Provide models or structures such as systems thinking for handling wicked problems.

• Assign students to complete the Identity Wheel activity and reflect on how their different identities shape their views of the wicked problems or shifts based on contextual factors. (resources on The Identity Wheel, Social Wheel, and reflection activities).

• Provide activities early in the course to train students on how to work and communicate in teams; to take different perspectives and viewpoints.

• Create collaborative activities regarding perspective taking.

• Evaluate assessment activities by focusing on several aspects of learning (students’ ability to participate; to solve the problem; grading the students on the ability to generate ideas, to offer different perspectives, and to collaborate; evaluation more on the process than the product, and self-reflection).

Team Conflict and Teamwork

“A central goal of this category is to have students wrestle with complex, multifaceted problems, and evaluate potential solutions from multiple points of view” (OSU Core Education, 2025). Working in teams provides an opportunity for teammates to learn from each other. However, teamwork is not always a straightforward and smooth collaboration. It can involve different opinions, disagreements, and conflict. While disagreements and differences can be positive for understanding others’ perspectives when taken respectively and rationally; when disagreements are taken poorly, differences in perspectives rises to become conflict and conflict could impact teamwork, morality, and outcomes negatively. Central to Seeking Solutions courses is collaborative teamwork where students will need to learn and apply their skills to work with others, including perspectives taking.

Aggrawal and Magana (2024) conducted a study on the effectiveness of conflict management training guided by principles of transformative learning and conflict management practice simulated via a Large Language Modeling (ChatGPT 3.5).

Fifty-six students enrolled in a systems development course were exposed to conflict management intervention project. The study used the five modes of conflict management based on the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI), namely: avoiding, competing, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. The researchers use a 3-phase (Learn, Practice and Reflect) transformative learning pedagogy.

- Learn phase: The instructor begins with a short introduction; next, students watch a youtube video (duration 16:16) on conflict resolution. The video highlighted two key strategies for navigating conflict situations: (1) refrain from instantly perceiving personal attacks, and (2) cultivate curiosity about the dynamics of difficult situations.

- Practice phase: students practice conflict management with a simulation scenario using ChatGPT 3.5. Students received detailed guidance on using ChatGPT 3.5.

- Reflect phase: students reflect on this session with guided questions provided by the instructor.

The findings indicate 65% of the students significantly increased in confidence in managing conflict with the intervention. The three most frequently used strategies for managing conflict were identifying the root cause of the problem, actively listening, and being specific and objective in explaining their concerns.

Application for Instructional Design

Providing students with opportunities to practice handling conflict is important for increasing their confidence in conflict management. Such learning activities should have relatable conflicts like roommate disputes, group project tension, in the form of role-play or simulation where students are given specific roles and goals, with structured after-activity reflection to guide students to process what happened and why, focusing on key conflict management skills such as I-messages, de-escalation, and reframing, and within safe environment.

Problem Solving

Creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication—commonly referred to as the 4Cs essential for the future—are widely recognized as crucial skills that college students need to develop. Creative problem solving plays a vital role in teamwork, enabling teams to move beyond routine solutions, respond effectively to complexity, and develop innovative outcomes—particularly when confronted with unfamiliar or ill-structured problems. Oppert et al. (2022) found that top-performing engineers—those with the highest levels of knowledge, skills, and appreciation for creativity—tended to work in environments that foster psychological safety, which in turn supports and sustains creative thinking. Lim et al. (2014) proposed to provide students with real-world problems. Lee et al. (2009) suggest to train students on fundamental concepts and principles through a design course. Hatem and Ferrara (2001) suggest using creative writing activities to boost creative thinking among medical students.

Application for Instructional Designers

We recommend on including an activity to train students on conflict resolution, as a warm-up activity before students work on actual course activities that involve teamwork and perspective taking. Also, it will be helpful to create guidelines and resources that students can use for managing conflict, and add these resources to teamwork activities.

Large Enrollment Online Courses

Teaching large enrollment science courses online presents a unique set of challenges that require careful planning and innovative strategies. Large online classes often struggle with maintaining student engagement, providing timely and meaningful feedback, and facilitating authentic practice. These challenges underscore the need for thoughtful course design and pedagogical approaches in designing large-scale online learning environments.

Mohammed and team (2021) assessed the effectiveness of interactive multimedia elements in improving learning outcomes in online college-level courses, by surveying 2111 undergraduates at Arizona State University. Results show frequently reported factors that increase student anxiety online were technological issues (69.8%), proctored exams (68%), and difficulty getting to know other students. More than 50% of students reported at least moderate anxiety in the context of online college science courses. Students commonly reported that the potential for personal technology issues (69.8%) and proctored exams (68.0%) increased their anxiety, while being able to access content later (79.0%) and attending class from where they want (74.2%), and not having to be on camera where the most reported factors decreased their anxiety. The most common ways that students suggested that instructors could decrease student anxiety is to increase test-taking flexibility (25.0%) and be understanding (23.1%) and having an organized course. This study provides insight into how instructors can create more inclusive online learning environments for students with anxiety.

Applications for Instructional Design

What we can do to help reduce student anxieties in large online courses:

1. Design task reminders for instructors, making clear that the instructor and the school care about student concerns.

2. Design Pre-assigned student groups if necessary

3. Design warm up activities to help students get familiar with their group members quickly.

4. Design students preferences survey in week 1.

5. Design courses that Make it easy for students to seek and get help from instructors.

As Ecampus moves forward with course development, these evidence-based practices will support the instructional design work to create high-quality online courses that provide students with the opportunities to develop, refine, and apply skills to navigate uncertainty, engage diverse viewpoints, and contribute meaningfully to a rapidly changing world. Ultimately, the Seeking Solutions initiative aligns with OSU’s mission to cultivate proactive global citizens, ensuring that graduates are not only career-ready but also prepared to drive positive societal change.

Conclusions

Instructional design for solution-seeking courses requires thoughtful course design that addresses perspective taking, team collaboration, team conflict, problem solving, and possibly large enrollments. Proactive conflict resolution frameworks, clear team roles, and collaborative tools help mitigate interpersonal challenges, fostering productive teamwork. Additionally, integrating structured problem-solving approaches (e.g., design thinking, systems analysis) equips students to tackle complex, ambiguous “wicked problems” while aligning course outcomes with real-world challenges. Together, these elements ensure a robust, adaptable curriculum that prepares students for dynamic problem-solving and sustains long-term program success.

References

Aggrawal, S., & Magana, A. J. (2024). Teamwork Conflict Management Training and Conflict Resolution Practice via Large Language Models. Future Internet, 16(5), 177-. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi16050177

Bikowski, D. (2022). Teaching large-enrollment online language courses: Faculty perspectives and an emerging curricular model. System. Volume 105

Head, B. (2008). Wicked Problems in Public Policy. Public Policy, 3 (2): 101–118.

McCune, V., Tauritz, R., Boyd, S., Cross, A., Higgins, P., & Scoles, J. (2023). Teaching wicked problems in higher education: ways of thinking and practising. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(7), 1518–1533. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1911986

Mohammed, T. F., Nadile, E. M., Busch, C. A., Brister, D., Brownell, S. E., Claiborne, C. T., Edwards, B. A., Wolf, J. G., Lunt, C., Tran, M., Vargas, C., Walker, K. M., Warkina, T. D., Witt, M. L., Zheng, Y., & Cooper, K. M. (2021). Aspects of Large-Enrollment Online College Science Courses That Exacerbate and Alleviate Student Anxiety. CBE Life Sciences Education, 20(4), ar69–ar69. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.21-05-0132

Oppert ML, Dollard MF, Murugavel VR, Reiter-Palmon R, Reardon A, Cropley DH, O’Keeffe V. A Mixed-Methods Study of Creative Problem Solving and Psychosocial Safety Climate: Preparing Engineers for the Future of Work. Front Psychol. 2022 Feb 18;12:759226. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759226. PMID: 35250689; PMCID: PMC8894438.

Veltman, M., J. Van Keulen, and J. Voogt. (2019). Design Principles for Addressing Wicked Problems Through Boundary Crossing in Higher Professional Education. Journal of Education and Work, 32 (2): 135–155. doi:10.1080/13639080.2019.1610165.

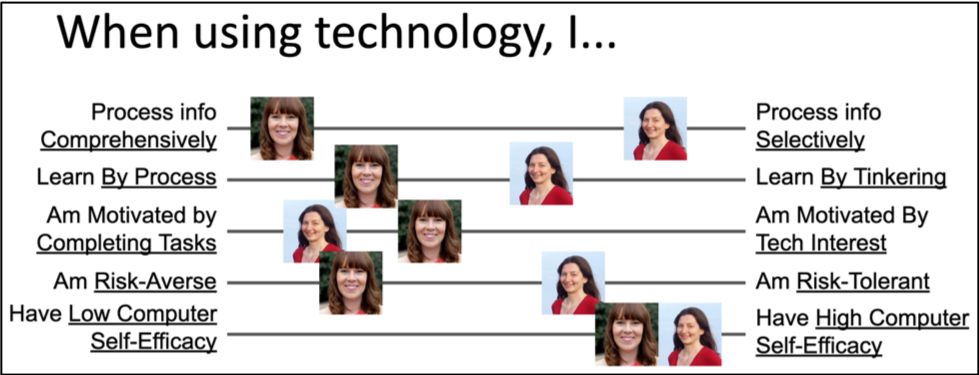

I recently volunteered to lead a book club at my institution for staff participating in a professional development program focused on leadership. The book we are using is The 9 Types of Leadership by Dr. Beatrice Chestnut. Using principles from the enneagram personality typing system, the book assesses nine behavioral styles and assesses them in the context of leadership.

I recently volunteered to lead a book club at my institution for staff participating in a professional development program focused on leadership. The book we are using is The 9 Types of Leadership by Dr. Beatrice Chestnut. Using principles from the enneagram personality typing system, the book assesses nine behavioral styles and assesses them in the context of leadership. I didn’t have a clear-cut answer but I recognized a strong desire to communicate this new-found awareness to others. My first thought was to find research articles. Google Scholar to the rescue! After a nearly fruitless search, I found two loosely-related articles. I realized I was grasping at straws trying to cull out a relevant quote. I had to stop myself; why did I feel the need to cite evidence to validate my incident? I was struggling with how to cohesively convey my thoughts and connect them in a practicable, actionable way to my job as an instructional designer. My insight felt important and worth sharing via this blog post, but what could I write that would be meaningful to others? I was stumped!

I didn’t have a clear-cut answer but I recognized a strong desire to communicate this new-found awareness to others. My first thought was to find research articles. Google Scholar to the rescue! After a nearly fruitless search, I found two loosely-related articles. I realized I was grasping at straws trying to cull out a relevant quote. I had to stop myself; why did I feel the need to cite evidence to validate my incident? I was struggling with how to cohesively convey my thoughts and connect them in a practicable, actionable way to my job as an instructional designer. My insight felt important and worth sharing via this blog post, but what could I write that would be meaningful to others? I was stumped! Who Cares? I Do

Who Cares? I Do