This post was written in collaboration with Mary Ellen Dello Stritto, Director of Ecampus Research Unit.

Quality Matters standards are supported by extensive research on effective learning. Oregon State University’s own Ecampus Essentials build upon these standards, incorporating OSU-specific quality criteria for ongoing course development. But what do students themselves think about the elements that constitute a well-designed online course?

The Study

The Ecampus Research Unit took part in a national research study with Penn State and Boise State universities that sought student insight into what elements of design and course management contribute to quality in an online course. Data was collected from 6 universities across the US including Oregon State in Fall of 2024. Students who chose to participate completed a 73-item online survey that asked about course design elements from the updated version of the Quality Matters Rubric. Students responded to each question with the following scale: 0=Not important, 1=Important, 2=Very Important, 3=Essential. A total of 124 students completed survey, including 15 OSU Ecampus students. The findings reveal a remarkable alignment between research-based best practices and student preferences, validating the approach taken in OSU’s Ecampus Essentials.

See the findings in data visualization form below, followed by a detailed description.

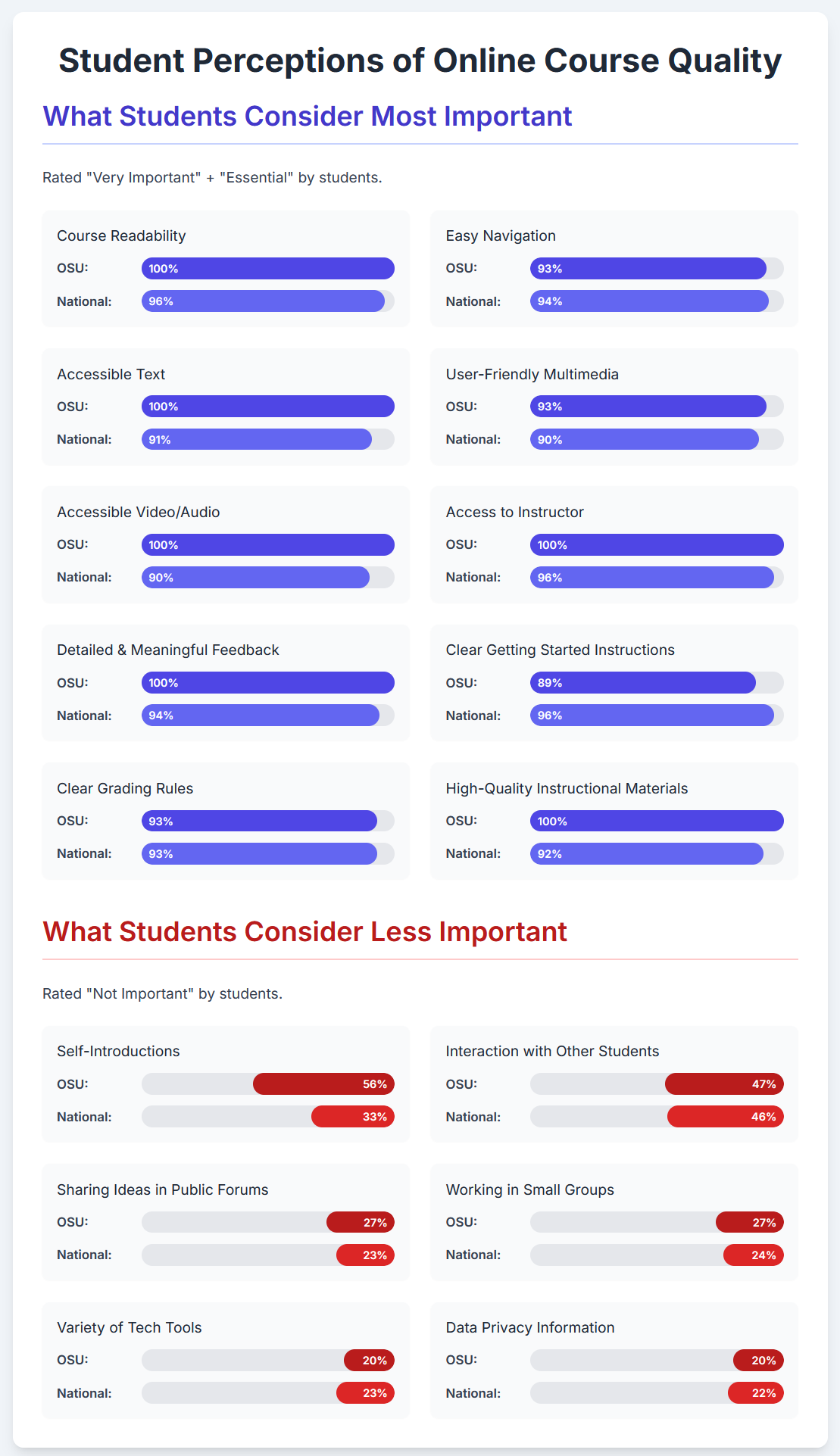

What Students Consider Most Important

Students clearly value practical, research-backed features that make online courses easier to navigate, more accessible, and more supportive of learning. The following items received the most ratings of “Essential” + “Very Important”:

| QM Standards and Study Findings | Related Ecampus Essentials |

| Accessibility and Usability (QM Standards 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.6): Every OSU student rated course readability and accessible text as “Very Important” or “Essential” (100%). Nationally, this was also a top priority (96% and 91%, respectively). Accessibility of multimedia—like captions and user-friendly video/audio—was also highly rated (100% OSU, 90% nationally). | Text in the course site is accessible. Images in the course are accessible (e.g., alt text or long description for images). The course design facilitates readability. All video content is accurately captioned. |

| Clear Navigation and Getting Started (QM Standards 1.1, 8.1): 93% of OSU students and 94% of the national sample rated easy navigation highly, while 89% of OSU students and 96% nationally said clear instructions for how to get started and where to find things were essential. | Course is structured into intuitive sections (weeks, units, etc.) with all materials for each section housed within that section (e.g., one page with that week’s learning materials rather than a long list of files in the module). Course is organized with student-centered navigation, and it is clear to students how to get started in the course. |

| Meaningful Feedback and Instructor Presence (QM Standards 3.5, 5.3): Students placed high importance on receiving detailed feedback that connects directly to course content (100% OSU, 94% nationally). The ability to ask questions of instructors was also essential (100% OSU, 96% nationally). | Assessments are sequenced in a way to give students an opportunity to build knowledge and learn from instructor feedback. The instructor’s plan for regular interaction with students in substantive ways during the course is clearly articulated. Information about student support specific to the course (e.g., links to the Writing Center in a writing course, information about TA open office hours, etc.) is provided. |

| Clear Grading Criteria (QM Standards 3.2, 3.3): 93% of OSU students and the full sample found clear, detailed grading rules to be essential. | Specific and descriptive grading information for each assessment is provided (e.g., detailed grading criteria and/or rubrics). |

| Instructional Materials (QM Standard 4.1): All OSU students and 92% nationally rated high-quality materials that support learning outcomes as very important or essential. | Instructional materials align with the course and weekly outcomes. A variety of instructional materials are used to appeal to many learning preferences (readings, audio, visual, multimedia, etc.). When pre-recorded lectures are utilized, content is brief and integrated into course learning activities, such as with interactive components, discussion questions, or quiz questions. Longer lectures should be shortened to less than 20 min. chunks. |

What Students Consider Less Important

The study also revealed areas where students expressed less enthusiasm:

| Study Findings | Related Ecampus Essentials |

| Self-Introductions (QM Standard 1.9): Over half of OSU students (56%) and a third nationally (33%) rated opportunities to introduce themselves as “Not Important”. | No specific EE |

| Peer Interaction (QM Standard 5.2): Students were lukewarm about peer-to-peer learning activities. Nearly half said that working in small groups is not important (47% OSU, 46% nationally). About a quarter didn’t value sharing ideas in public forums (27% OSU, 24% nationally) or having learning activities that encourage them to interact with other students (27% OSU, 23% nationally). | Three forms of interaction are present, in some form, in the course (student/content, student/instructor, student/student). |

| Technology Variety and Data Privacy Info (QM Standards 6.3, 6.4): Some students questioned the value of using a variety of tech tools (20% OSU, 23% nationally rated this as “Not Important”) or being given info about protecting personal data (20% OSU, 22% nationally). | Privacy policies for any tools used outside of Canvas are provided. |

Student Comments

Here are a few comments from Ecampus students that illustrate their opinions on what makes a quality course:

- “Accessible instructional staff who will speak to students in synchronous environments. Staff who will guide students toward the answer rather than either treating it like cheating to ask for help at all or simply giving out the answer.”

- “A lack of communication/response from teachers and no sense of community” – was seen as a barrier.

- “Mild reliance on e-book/publisher content, out-weighed by individual faculty created content that matches student deliverables. In particular, short video content guiding through the material in short, digestible amounts (not more than 20 minutes at a go).”

- “When there aren’t a variety of materials, it makes it hard to successfully understand the materials. For example, I prefer there to be lectures or videos associated with readings so that I understand the material to the professor’s standards. When I only have reading materials, I can sometimes misinterpret the information.”

- “Knock it off with the discussion boards, and the ‘reply to 2 other posts’ business. This is not how effective discourse takes place, nor is it how collaborative learning/learning community is built.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

The takeaways? This research shows that students recognize and value the same quality elements emphasized in OSU’s Ecampus Essentials:

- Student preferences align with research-based standards – Students consistently value accessibility, clear structure, meaningful feedback, and purposeful content.

- Universal design benefits everyone – Students’ strong preference for accessible, well-designed courses supports the universal design principles embedded in the Ecampus Essentials.

However, there is always room for improvement, and these data provide some hints. Many students don’t immediately see value in peer interactions and collaborative activities, even though extensive educational research shows these are among the most effective learning strategies. Collaborative learning is recognized as a High Impact Practice that significantly improves student outcomes and critical thinking. This disconnect suggests we need to design these experiences more thoughtfully to help students recognize their benefits. Here are some suggestions:

- Frame introductions purposefully: Instead of generic “tell us about yourself” posts, connect introductions to course content (“Introduce yourself and share an experience related to the topic of this course”).

- Design meaningful group work: Create projects that genuinely require collaboration and produce something students couldn’t create alone.

- Show the connection: Explicitly explain how peer interactions help students learn and retain information better, and the value of teamwork for their future jobs.

- Start small: Begin with low-stakes peer activities before moving to more complex collaborations.