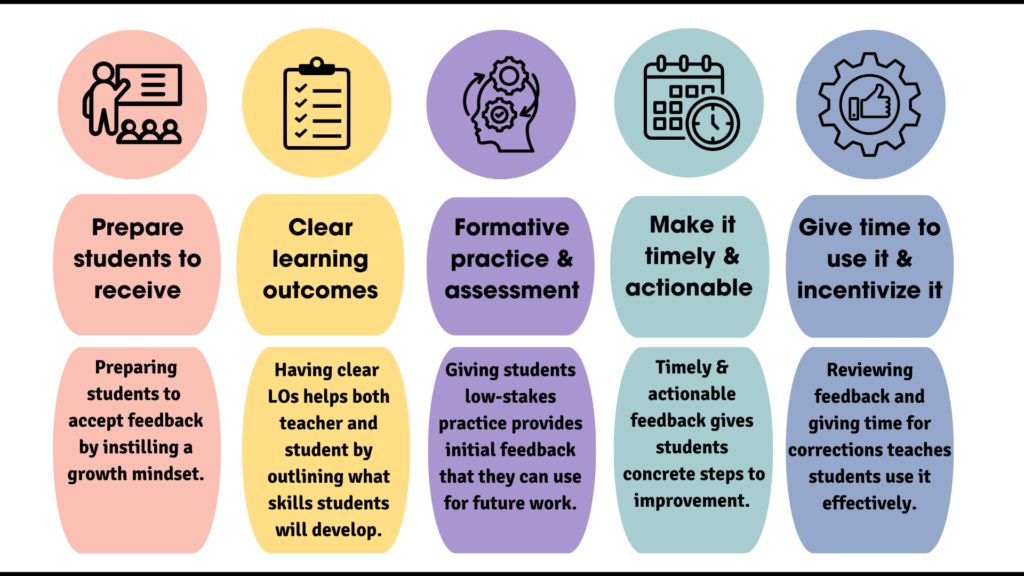

In part one of this two-part blog series, we focused on setting the stage for a better feedback cycle by preparing students to receive feedback. In part two, we’ll discuss the remaining steps of the cycle- how to deliver feedback effectively and ensure students use it to improve.

In part one, we learned about the benefits of adding a preliminary step to your feedback system by preparing students to receive suggestions and view them as helpful and valuable rather than as criticism. If you haven’t read part one, I recommend doing so before continuing. This first crucial but often overlooked step involves fostering a growth mindset and creating an environment where students understand the value of feedback and learn to view it as a tool for improvement rather than criticism.

Step 2: Write Clear Learning Outcomes

The next step in the cycle is likely more familiar to teachers, as much focus in recent decades has been placed on developing and communicating clear, measurable learning outcomes when designing and delivering courses. Bloom’s Taxonomy is commonly used as a reference when determining learning outcomes and is often a starting point in backwards design strategy. Instructors and course designers must consider how a lesson, module, or course aligns with the learning objectives so that students are well-equipped to meet these outcomes via course content and activities. Sharing these expected outcomes with students, in the form of CLOs and rubrics, can help them to focus on what matters most and be better informed about the importance of each criterion. These outcomes should also inform instructors’ overall course map and lesson planning.

Another important consideration is ensuring that learning outcomes are measurable, which requires rewriting unmeasurable ones that begin with verbs such as understand, learn, appreciate, or grasp. A plethora of resources are available online to assist instructors and course designers who want to improve the measurability of their learning outcomes. These include our own Ecampus-created Bloom’s Taxonomy Revisited and a chart of active and measurable verbs from the OSU Center for Teaching and Learning that fit each taxonomy level.

Step 3: Provide Formative Practice & Assessments

The third step reminds us that student learning is also a cycle, overlapping and informing our feedback cycle. When Ecampus instructional designers build courses, we try to ensure instructors provide active learning opportunities that engage students and teach the content and skills needed to meet our learning objectives. We need to follow that up with ample practice assignments and assessments, such as low-stakes quizzes, discussions, and other activities to allow students to apply what they have learned. This in turn allows instructors to provide formative feedback that should ideally inform our students’ study time and guide them to correct errors or revisit content before being formally or summatively graded. Giving preliminary feedback also gives us time to adjust our teaching based on how students perform and hone in on what toreview before assessments. Providing practice tests or assignments or using exam wrappers, exit cards, or “muddiest point” surveys to collect your students’ feedback can also be an important practice that can help us improve our teaching.

Step 4: Make Feedback Timely and Actionable

Step four is two-fold, as both the timeliness and quality of the feedback we give are important. The best time to give feedback is when the student can still use it to improve future performance. When planning your term schedule, it can be useful to predict when you will need to block off time to provide feedback on crucial assignments and quizzes, as a delay for the instructor equates to a delay for students. Having clear due dates, reminding students of them, and sticking to the timetable by giving feedback promptly are important aspects of giving feedback.

To be effective, feedback must focus on moving learning forward. It should target the identified learning gap and suggest specific steps for the student to improve.. For a suggestion to be actionable, it should describe actions that will help the student do better without overloading them with too much information- choose a few actionable areas to focus on each time. Comments that praise students’ abilities, attitudes, or personalities are not as helpful as ones that give them concrete ways to improve their work.

Step 5: Give Time to Use Feedback and Incentive it

The last step in the cycle, giving students time to use the feedback provided, is often relegated to homework or ignored altogether. Feedback is most useful when students are required to view it and preferably do something with it, and by skipping this important step, the feedback might be ignored or glanced over perfunctorily and promptly forgotten. To close the loop, students must put the feedback to use. This can be the point where your feedback cycle sputters out, so be sure to make time to prioritize this final step. Students may need assistance in applying your feedback. Guiding students through the process, and providing scaffolds and models for using your feedback can be beneficial, especially during the initial attempts.

In my experience, it never hurts to incentivize this step: this can be as simple as adding points to an assignment for reflecting on the feedback given or giving extra credit opportunities around redone work. As a writing teacher, I required rewrites for work that scored below passing and offered to regrade any rewritten essays incorporating my detailed feedback. This proved to be a good solution, and while marking essays was definitely labor intensive, I was rewarded with very positive feedback from my students, often commenting that they learned a lot and improved significantly in my courses.

Considerations

A robust feedback cycle often includes opportunities for students to develop their own feedback skills by performing self-assessments and peer reviews. Self-assessment helps students in several ways, promoting metacognition and helping them learn to identify their own strengths and weaknesses. It also allows students to reflect on their study habits and motivation, manage self-directed learning, and develop transferable skills. Peer review also provides valuable practice honing their evaluative skills, using feedback techniques, and giving and receiving feedback, all skills they will find useful throughout adulthood. Both self-assessment and peer review give students a deeper understanding of the criteria teachers use to evaluate work, which can help them fine-tune their performance.

Resources for learning more:

Feedback

- How to Give Feedback | Teaching + Learning Lab

- How to give and receive feedback effectively – PMC

- Teacher Feedback to Improve Pupil Learning | EEF & Summary of recommendations

- Staff Resource Snapshot Guide The provision of constructive feedback to students: The Why? What? How?’

- The Feedback Sandwich: Should You Use It? (Pros and Cons)

- How to Give the Most Effective Feedback

- 20 Ways To Provide Effective Feedback For Learning

- Actionable feedback – Evidence Based Education

- Self-Assessment | Center for Teaching Innovation

Learning Outcomes

- Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy: Action Verbs for Writing Learning Outcomes

- OSU Video: Meaningful, Measurable, Manageable CLOs w/accompanying handout

Self-assessment

- Exam Wrappers – Eberly Center – Carnegie Mellon University

- Lots of downloadable samples of exam wrappers for different subject areas.

- Self-Assessment | Center for Teaching Innovation