“Annotation provides information, making knowledge more accessible. Annotation shares commentary, making both expert opinion and everyday perspective more transparent. Annotation sparks conversation, making our dialogue – about art, religion, culture, politics, and research – more interactive. Annotation expresses power, making civic life more robust and participatory. And annotation aids learning, augmenting our intellect, cognition, and collaboration. This is why annotation matters.”

Annotation

When you think back to your early college years, you may remember your professor assigning a text to annotate. Annotating a text has long been a common task in higher education, one that ideally promotes deeper reading, interaction with, and comprehension of important texts. Annotation assignments vary widely but the traditional paper-based type of annotation asks readers to respond to a text as it is read, physically marking or highlighting the text itself and perhaps writing in the margins. This approach allows students to enter into a dialogue with the text by recording their responses to the text, adding reflections or critiques, and anchoring those reactions to a specific place in the text. When students annotate a text, they are working their way through skills that span the levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, from remembering to predicting, connecting, analysing, and evaluating. Annotation, at its best, encourages active engagement with a text beyond the surface level, promoting deeper critical thinking and stronger retention of concepts.

While this is, of course, fantastic individual practice, the nature of traditional annotation assignments is primarily solitary. Today’s classrooms place more of an emphasis on 21st century skills such as group and collaborative study, and new digital tools have been developed that have revolutionized what, how, and with whom we can annotate. So-called social annotation has picked up speed with the growing popularity of two major players, Perusall and Hypothes.is, bolstered by the sudden shift to remote learning in 2020. Online instructors seeking ways to replicate the back and forth, robust discussion of a face-to-face class have found these tools a fitting substitute, and the asynchronous format of the discussion means these tools have a place in all modalities.

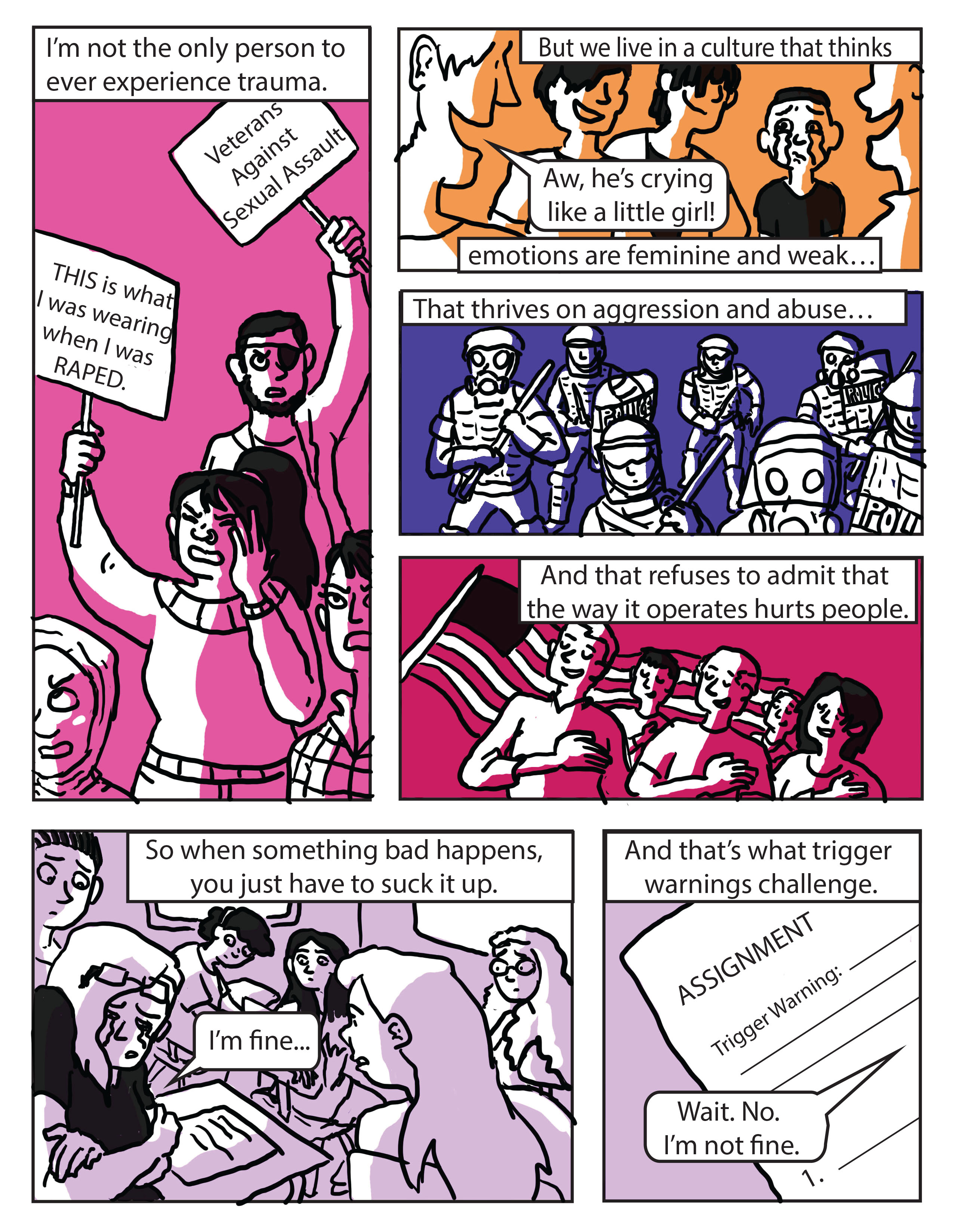

Equity, Inclusion, & Community

“As a teaching method, critical social annotation allows for equitable conversations to unfold in-line with the knowledge being presented in course texts. In this way, it can potentially subvert or even redress instances of inequity in course content.”

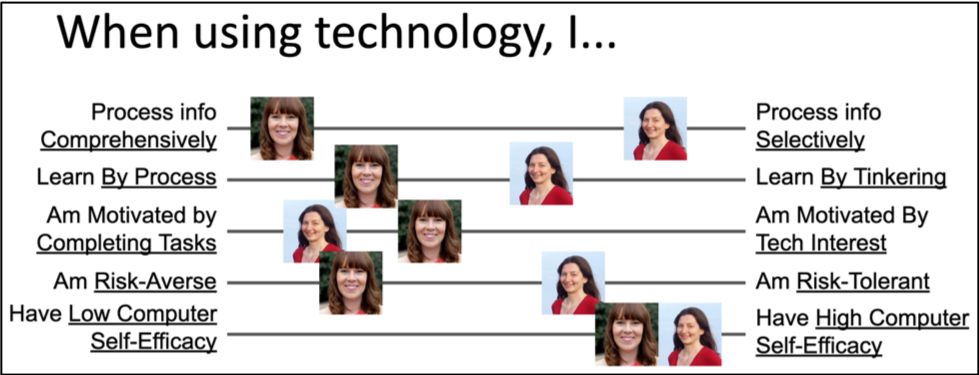

Social annotation platforms increase equity and inclusion in a course in several ways. Digital annotation platforms offer students a variety of ways to connect with material, allowing students to post links, images, video, and more in response to the text, their peers, and other annotators. By putting students’ ideas front and center, social annotation can empower learners to take initiative and experience more feelings of control over their educational process. Unlike the fast paced back and forth of traditional face-to-face discussions, the nature of digital social annotation allows students more time to engage with the text and to take as long as they need to post and respond (within the assignment boundaries). Additionally, the major platforms discussed in this post feature easy-to-use controls that require little technical expertise to use. They also boast comprehensive accessibility features that combine to provide inclusivity to a wide range of student needs.

Social Annotation as Collective Construction of Meaning

One major difference between today’s digital social annotation and traditional solitary practice is that when students in a particular class collectively annotate a text using one of the digital platforms available today, they are actively building knowledge and understanding as a group. By sharing the document for collective annotation, the act of annotating itself becomes a social activity and contributes to the interaction of individuals within the group. Socially annotating a text is one of the best ways to encourage close and active reading skills, with many studies reporting higher levels of student comprehension of socially annotated materials. Students who collectively annotate a text are entering into an exchange of questions, opinions, perspectives, and reactions to a text, engaging in a discourse with their peers (and facilitator, usually) and by extension learning from and with them. The process of a social annotation assignment allows students to see knowledge creation in action and become co-creators.

Use of social annotation in asynchronous online courses can also increase sociability within an otherwise geographically remote, disparate group of students. Asynchronous instructors sometimes struggle to provide opportunities for real social interaction and building of community given the limits of the modality. An often unstated goal of higher education is to socialize students to academic community norms, and social annotation allows students to experience and practice some of these. For example, students annotating collectively learn appropriate language for responding to peers’ ideas and criticisms, develop online academic social identities, and gain experience with navigating power dynamics within the higher education classroom.

Ready to Try It Out?

Adding social annotation to a course involves matching the task to your learning outcomes, deciding which readings would be best suited to annotation, and choosing your online annotation platform.

Assignments can be tailored to meet a variety of instructional purposes and goals:

- Recognizing formatting of various documents

- Providing background or contextual information

- Learning academic norms for responding to peers- supporting, agreeing, disagreeing

- Drafting questions and responses that are rigorous and meaningful

- Determining main points vs. supporting details

- Distinguishing fact from opinion

- Identifying themes, tone, biases, author’s purpose, rhetorical devices, etc.

- Learning and practicing discipline-specific writing and reading conventions

- Connecting the material to the field of study, to their own practice, or to other course materials

- Developing evaluative and analytical skills

- Considering differing perspectives and viewpoints in constructing knowledge

- Facilitating a deeper understanding of difficult passages

Some best practices to consider when using collective annotation online:

- Remind students that they have already practiced annotation in their everyday lives (reading and making your own notes in your inherited cookbook, reading your teacher’s remarks on your essay, leaving comments on a colleague’s report)

- Model annotation with a fun text first

- Seed the reading with your own comments, questions, and notes to help guide students

- Situate the social annotation assignment within the context of the course and make clear the intentions you have for the activity

- If the activity is to be graded, be sure students know the grading criteria, preferably by providing a rubric

- Annotation assignments are ideal for small group activities, and some platforms automatically create groups

- Be prepared to provide guidelines for behavior and etiquette among students and to need to enforce these guidelines if students step out of line

- Monitor the discussion and provide nudges, likes, upvotes, or validations, and otherwise engage with the dialogue throughout the assignment

- If the platform allows tagging, do so- students get notified when someone responds to their post or asks a question, a convenience which increases the likelihood of them returning to the assignment for further interaction

Social Annotation Tools: The Major Players

Perusall (stand-alone site/integrated into various LMS, including canvas)

Perusall is a collective annotation platform developed by Harvard University following a major research initiative into online collective annotation. Perusall offers free accounts for teachers and students at the basic level with options for institutions to integrate the tool into their LMS. The platform allows educators to use Perusall directly for stand-alone courses and upload their own materials for annotation as well as partner with their textbook catalog to purchase and annotate textbooks directly. For integrated LMS users, Perusall offers seamless grade pass back and options for pass/no pass grading as well as a robust automatic AI grading system that saves time and effort. Some instructors have also used Perusall for peer review to great effect using student-uploaded documents. *recommended tool for Ecampus courses

Hypothes.is (Google Chrome browser extension)

Hypothes.is is a groundbreaking new tool that bypasses restrictions of the classroom and enables anyone anywhere to annotate any webpage via a unique delivery system- as a browser extension that creates a layer over any webpage. This open source, free tool can revolutionize how we view and interact with web pages as well as texts by allowing us to save our annotations privately as well as publicly, inviting the world at large to socially annotate with us. Hypothes.is is also available as an integrated tool in most LMSs. The company also hosts the AnnotatED community, a group of users that hosts events, studies, and conferences to learn best practices for the tool. *recommended tool for research with a wider audience.

Sources

Adapting to Disciplinary Literacy Conventions – Open English @ SLCC

Innovation | Cégep Vanier College

Kalir, Remi H., and Garcia, Antero. Annotation. United States, MIT Press, 2021.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Annotation/ejoiEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Social Annotation | Center for Teaching Innovation

Social Annotation – Pedagogical Support and Innovation Pedagogical Support and

Social Annotation and an Inclusive Praxis for Open Pedagogy in the College Classroom

(image from pxfuel.com)

(image from pxfuel.com)