Assignments are an integral component of the educational experience to guide the teaching and learning processes. In fact, Dougherty (2012) contends that assignments are instructional events that aim to teach for learning, that is “recipes for instructional events— lessons in the best sense— and their main function is to create a context for teaching new content and skills and practicing learned ones.” (p. 23). Assignments as instructional plans provide students with the opportunities to apply concepts they studied in the class. Further, through assignments, students can demonstrate the skills developed in a unit of content in more concrete ways and aligned to the goals of the course.

In my consultations with instructors I often hear them raise concerns about course assignments. These concerns range from making assignments more practical and relevant, clarifying the purpose and instructions, integrating problem-solving and critical thinking, to including authentic and experiential tasks. In addition, I hear instructors mention that some assignments that students submit are incomplete, offer superficial and unsubstantiated arguments (i.e., written reports), focus on tangential ideas, have been googled, reflect bias, and are simple opinions using non-credible sources. These concerns are very valid and it is important to examine the assignments deeper. What I have noticed is that some assignment descriptions lack a purpose and clarity. In a word, assignments need to be transparent.

Determining the structure of an assignment bears the questions of how can instructors make the assignments learning events that are clear and relevant enough for students? how can students not only demonstrate what they learn, but also use the assignments as catalysts for further intellectual and academic challenges? Let’s take a closer look at transparency.

Transparency

The first time I heard about transparency in assignment design was at the Wakonse Teaching and Learning conference a few years go. Several sessions and small group activities at the conference showed us that the assignments need to have a clear structure, detailed instructions, and a grading criteria. Obviously! I said to myself at the time. However, the reality is that assignments tend to be reduced to a list of instructions, tasks that students need to complete and submit for a grade. In some cases these instructions vaguely indicate the grading criteria in terms of the format and style (i.e., number of words, font size, spacing).

The underlying framework for transparent assignments is a structure that clearly describes the purpose of the assignment, the instructions or tasks, and the grading criteria (Dougherty, 2012; Winkelmes, 2013; Winkelmes, Bernacki, Butler, Zochowski, Golanics, & Weavil, 2016). Winkelmess and colleagues (2016) draw from three theoretical bases to support the three-stage framework: metacognition, agency, and performance monitoring. Contrastively, Dougherty (2012) draws from instructional strategies informed by backward design and alignment to outcomes to set the assignment structure. In this framework, instructors deliberately design the assignment for high quality learning experience and relevance to students. In their research study, Winkelmess and colleagues (2016) found that students who received transparent assignments showed evidence of greater learning in three areas related to student success: academic confidence, sense of belonging, and mastery of skills.

Designing transparent assignments involve creating a clear and coherent architecture. Through this structure students can think deeper about the concepts studied, focus their attention on particular topics, make connections to real-world contexts, and see the relevance for their future lives and goals (Dougherty, 2012). In doing so, instructors need to create a harmonious structure that clearly explains why students need to do an assignment, what is the assignment about, how to do the assignment, and how they will be graded on it.

When I presented this architecture to one instructor, he replied “you are asking me to tell students the answer! Why would I need to hand-hold students in this way when I want them to be problem-solvers and critical thinkers?” While this comment is valid, and also paralyzed me for a few seconds, I engaged the instructor in discussing what the assignments need to be clear. For instance, we talked about how students will know what to do, why students should care about completing the assignment (besides the grade), and how students will meet the expectations if they don’t know the purpose and the way to complete it. In addition, I said “you want students to be problem-solvers of the content and topics, not problem-solvers of the assignment design.”

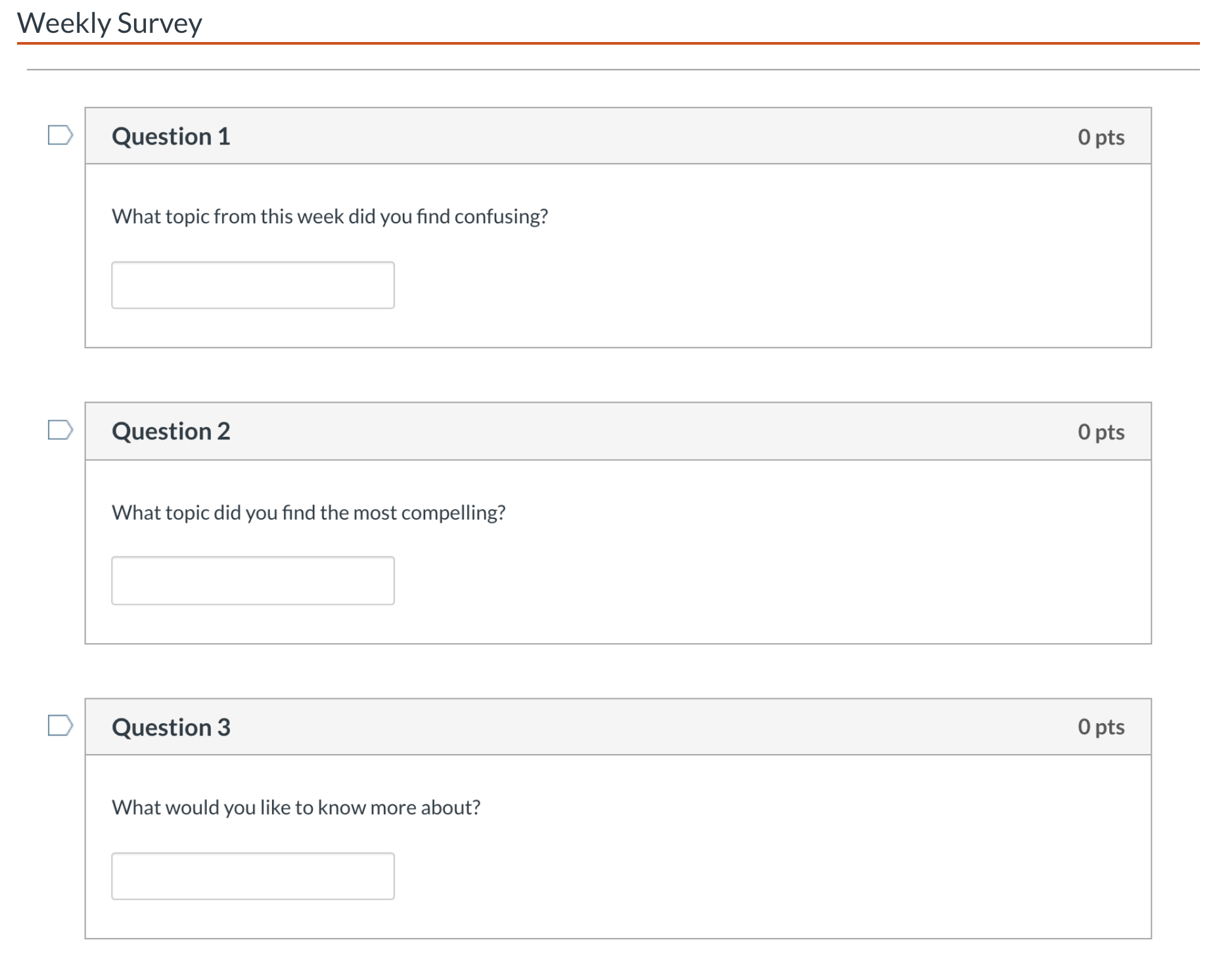

A transparent assignment should have the following three basic components: purpose, task, and grading criteria.

Purpose

The starting point in an assignment is to be able to answer the question of why? Why will students learn from this assignment? Why will students need to complete this assignment? Why is this assignment important in students’ learning? Stating the purpose of the assignment serves a two-fold objective. First, it gives the instructor a frame of reference for creating an activity that is relevant and meaningful to students, and that connects to the learning outcomes. Second, the purpose of the assignment gives students a focus and a sense of direction.

Winkelmes (2013) suggests establishing the purpose in terms of the skills students will practice and the knowledge they will gain. In addition, the purpose can also be determined by contextualizing the learning outcomes in practical ways within the activity.

Task

You can call it tasks, details, instructions, steps, or other. In this structure, the instructor describes what students need to do, what resources they can use, and the expectations of the assignments. Having a clear set of instructions makes the assignment more rigorous and helps students produce more high-quality work.

Grading Criteria

Providing the criteria of how the assignment will be graded will also give students a sense of clarity and direction. Clear expectations through a rubric or grading guidelines helps students adhere to the outcomes of the assignment. Winkelmes (2013) suggests including several examples of real-world problems so students can see how the application of knowledge and skills will look like.

Remarks

A transparent assignment should have a well-structured framework or an architecture of steps. Transparency in assignments is a mindset, a way of thinking, the vision that students are given clear and relevant learning events that allow them to demonstrate their learning, and foster their engagement. Transparent assignments can be designed as stand-alone pieces or as a multi-stage assignment. Multi-stage assignments can build on cognitive complexity, include multiple skills, and extend learning to outside the class. In our next blog, I will look at how to design multi-stage assignments.

Sources

Dougherty, E. (2012). Assignments matter: Making the connections that help students meet standards. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Winkelmes, M. 2013. “Transparency in Learning and Teaching: Faculty and Students Benefit Directly from a Shared Focus on Learning and Teaching Processes.” NEA Higher Education Advocate, 30(1), 6-9.

Winkelmes, M. A., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Weavil, K. H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success. Peer Review, 18(1/2), 31-36.