The following is a guest blog post from Andrea De Lei. Andrea completed an Instructional Design internship with OSU Ecampus during Fall 2021.

WHY SELF-CARE IS IMPORTANT FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS

Stress is not a new concept to college students, faculty, or staff. By teaching and incorporating self-care and overall health into your curriculum and design, your students can better manage stress and the host of obligations they may have to balance: full course loads, employment, commitments to their family and friends, internship, and networking opportunities. The Covid-19 pandemic this past two years added additional stressors both in teaching and engaging with students -added isolation and global pandemic stressors. To say these past two years was challenging would be an understatement. One way to get students and ourselves to practice self-care is to incorporate it into our lessons.

In a 2016 survey of Canadian university students,

- 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by all they had to do,

- over 40% reported stress as the number one impact on their academic performance,

- 71% wanted more information on stress reduction (Alberta Canada Reference Group, 2016).

BURNOUT IS NOT NEW

College students are experiencing high rates of anxiety, depression, burnout, and unhealthy coping mechanisms to manage their stress. A study done by Ohio State University showed that in August 2020, student burnout was at 40%. When Ohio State conducted the survey again in April 2021, it was 71%, highlighting the continued struggles of student mental health and the need for higher education to create a holistic approach centered around student health and wellness. Teaching self-care can help instructors prevent student burnout, interact more effectively with students and create a culture more conducive to learning. Teaching and practicing self-care is necessary to balance and prevent burnout (Tan & Castillo, 2014).

BENEFITS OF ADDING SELF-CARE INTO THE CURRICULUM

The past year was filled with unprecedented events; social injustices, global pandemic, and increased stress diminished our prioritization of self-care. Increased isolation and loneliness mixed with online learning have created a void in identifying when someone needs help. Traditional self-care checkpoints are not as prominent for distance online learners as students learning in-person. Instructors can play a crucial role in supporting student mental health and wellbeing by incorporating self-care into their curriculum.

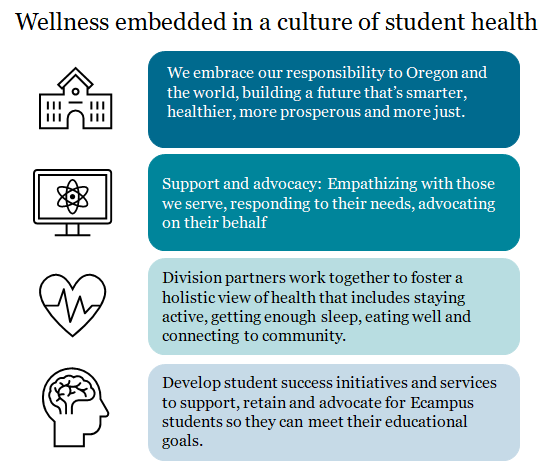

Image 1:Wellness Embedded in a Culture of Student Health visual aid created by Andrea De Lei; content cited from Oregon State University (OSU), OSU Ecampus and OSU Student Affairs webpages.

HOW CAN YOU ADD SELF-CARE INTO THE CURRICULUM

Supporting university-wide mental health initiatives is critical to student success and wellbeing. But, how do I add self-care in my online math course? Understanding the values of your university, department, campus culture, and needs of the students can help align these values into the curriculum and add self-care into any online course. A key component is giving students opportunities to plan time to incorporate self-care into their busy and stressful lives.

“Self-care has an experiential component in that it includes reflection and action in conjunction with real-world encounters” (Hroch, 2013, p. 5). Consider one or multiple assignments focused on self-care and wellness. Adding self-care and wellness can look like a wellness self-assessment, engaging in self-care activities and reflecting on that experience, incorporating additional resources into the syllabus or providing a “get out of jail [assignment] card.”

Image 2: Self-Care and Wellness Discussion Module online Canvas course created by Andrea De Lei, 2021.

O’Brien-Richardson (2019) recommends four self-care strategies to support students: making yourself available, pausing for mental breaks, allowing for moments of self-reflection, and equalizing class participation. Suggested self-care activities for students can include an array of possibilities. From physical, spiritual, emotional, social and many more. Self-care is personal to the individual and looks different for everyone. Some examples include:

- Physical self-care activities

- Go on a run

- Practice yoga

- Get some sleep

- Spiritual/Mindfulness self-care activities

- Read poetry

- Meditate

- Take a milk bath

- Emotional self-care activities

- Write your feelings down.

- Cry and laugh

- Practice self-compassion.

- Social self-care activities

- In-person or virtual coffee or lunch with a friends/family

- Phone or virtual facetime

- Join a [insert interest] club

- Watch a movie or show with friends/family

THERE’S ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT

To sum it up, adding self-care and wellness into the online curriculum can help students take time for themselves, destress, self-reflect, and create healthy habits to become better involved and engaged students. Instructors can continue to support students in various ways: self-care assignments, making yourself available, pausing for mental breaks, and allowing for moments of self-reflection.

References

Alberta Canada Reference Group (2016). Executive summary. American college health association. National College Health Assessment.

Hroch, P. (2013). Encountering the “ecopolis” Foucault’s epimeleia heautou and environmental relations. ETopia online initiative of TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies. Retrieved from http://etopia.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/etopia/article/view/36563/33222

O’Brien-Richardson, P. (2019, October 14). 4 Self-care strategies to support students. Harvard Business Publishing Education. https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/4-self-care-strategies-to-support-students

Saken, P., & Gerad, D. (2021, July 26). Survey: Anxiety, depression and burnout on the rise as college students prepare to return to campus [Student Mental Health MMR news release]. The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. http://osuwmc.multimedia-newsroom.com/index.php/2021/07/26/survey-anxiety-depression-and-burnout-on-the-rise-as-college-students-prepare-to-return-to-campus/

Tan, S. Y., & Castillo, M. (2014). Self-care and beyond: A brief literature review from a Christian perspective. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 33(1), 90-95.

(image from pxfuel.com)

(image from pxfuel.com)