By Grace Deitzler

Improvements in DNA sequencing technology have allowed scientists to dig deeper than ever before into the intricacies of the microbes that inhabit our gut, also called the gut microbiome. Massive amounts of data – on the scale of pentabytes – have been accumulated as labs and institutes across the globe sequence the gut microbiome in an effort to learn more about its inhabitants and how they contribute to human health. But now that we have all of this data (and more accumulating all the time), the challenge becomes making sense of it.

This is a challenge that Christine Tataru, a rising fifth year PhD student in the Department of Microbiology, is tackling head-on. “My research is trying to understand what a ‘healthy’ gut microbiome actually looks like, how it ‘should’ look, and to do so in a way that is integrative,” she explains.

An integrative approach looks at all of the processes and relationships that are occurring between all of the trillions of microorganisms in our gut, and the cells within our body. Previous microbiology dogma focused on the behavior and impact of singular species such as pathogens, but as we learn more about microbiomes, this approach becomes limiting. There are a vast number of relationships that can occur between microbes and human cells. And there are many different lenses through which we can look at this system: taking a census of what microbes are present; tracking the genes that are present rather than just the microbes (this tells us about the functions that might be carried out); and what proteins or metabolites are actually present, whether those are created by the bacteria or the host. Each piece of the puzzle allows us a glimpse of the massively complex system that is the gut microbiome.

“It’s difficult for a human brain to keep track of these relationships and sources of variations, so I use computer algorithms to try to get a picture of what is happening, and what that might mean for health.”

It’s an approach that makes sense for the Stanford-trained computer-scientist-turned-biologist. Christine recalls a deep learning class in college in which a natural language processing algorithm on the whiteboard struck her with inspiration: what if instead of being applied to words, this algorithm could be applied to gut microbiomes? The thought stuck with her and when she came to OSU to pursue her PhD, she already had a clear goal in mind for what she wanted to do.

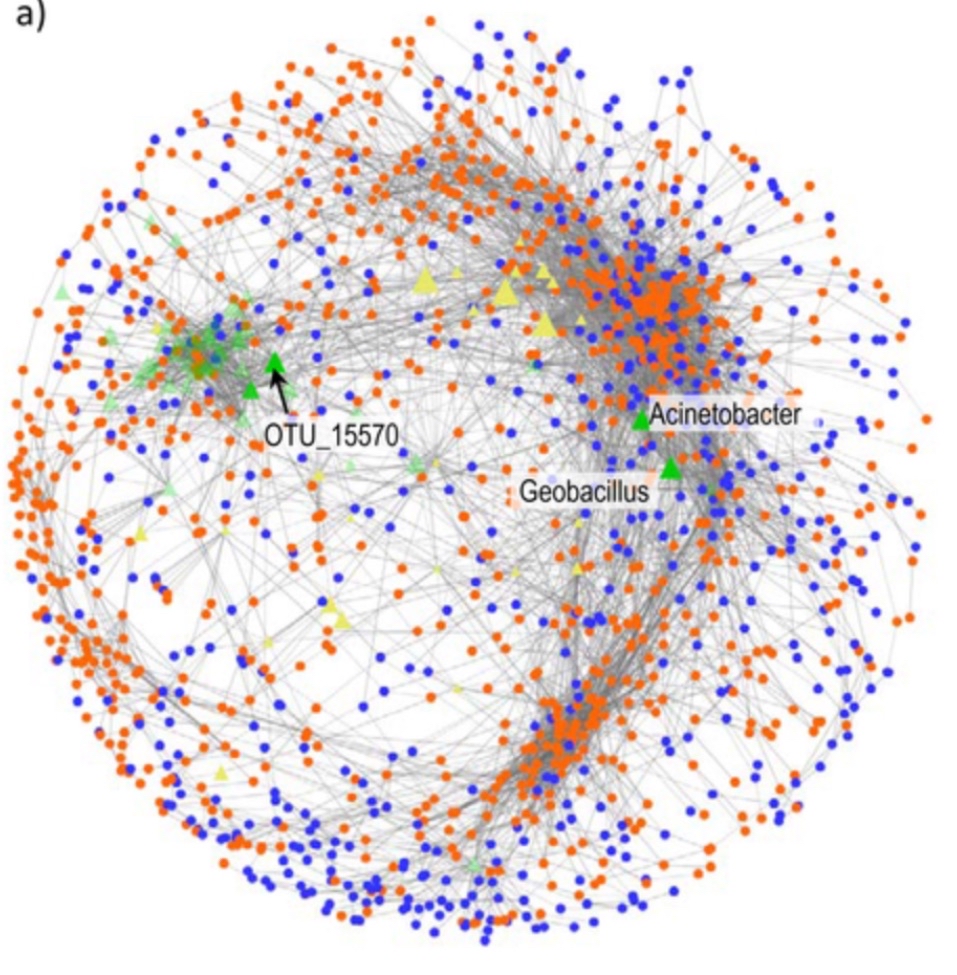

The natural language processing and interpretation algorithm treats words in a document as discrete entities, and looks for patterns and relationships between words to gain context and “understand” the contents. A computer can’t really understand what words mean linguistically and with the complex nuances that natural language presents, but they are really good at looking for patterns. It can look at what words occur together frequently, what words never occur together, and what words share a ‘social network’ — words that don’t appear together, but appear with the same other words. Christine has developed a way to apply this algorithm to large gut microbiome datasets: using this approach to identify what microbes frequently appear together, which don’t, and which share ‘social networks’. This produces clusters of microbes, or what she refers to as ‘topics’, which can then be interpreted by humans to try to understand how these clusters relate to certain aspects of health. You can read more about this method in her recent PLOS Computational Biology publication here.

It’s quite the challenging undertaking: no one has done this type of approach before, and even when the clusters are generated, we still need to be able to interpret what it means – why is it interesting or important that these microbes occur with each other and also correlate with these genes or metabolites? Biologically, what does it actually mean?

The question of biological meaning prompted Christine to pivot to a more traditional ‘wet lab’ biology approach. “Who gave this computer scientist a pipette,” she jokes. But to be perfectly honest, it makes a lot of sense: who better to investigate the hypotheses that can be generated by computers than the scientist who wrote the code?

Taking the ‘integrative approach’ to the next level, she now works on recapitulating the environment of the gut microbiome on a chip in the lab. The organ-on-a-chip system is a fairly new approach to studying biological mechanisms in a way that better mimics the naturally occurring environment. In Christine’s case, she is using a ‘gut on a chip’, which is made of a thin piece of silicone with input and output channels. The silicone is split by a microporous membrane in such a way that two different kinds of cells can be grown, one on the top layer and one on the bottom. What makes this system unique as compared to traditional cell culture is that the channels and membrane allow for constant flow of growth media, which physically simulates the flow of blood over the cells. It can also mimic peristalsis, which is the stretching and relaxing of intestinal cells that helps push food and nutrients through the digestive tract. It’s a sophisticated system, and one that allows her a high degree of control over the environment. She can use this system to mimic Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and then add in specific microbes or combinations of microbes to see how the gut cells respond, using findings from her algorithm results to inform what kinds of additions might have anti-inflammatory effects.

This innovative approach provides Christine another lens through which to view the relationship between the gut microbiome and health. Though she will be finishing her doctorate at the end of the year, the curiosity doesn’t end there – “Broadly, my life goal to some extent has always been to make ways for people to help people.” Whether that’s pipeline and methods development or building the infrastructure to study complex biological relationships, Christine’s innovation-driven approach is sure to lead to huge strides in our understanding of how the tiny living things in our gut influence our health, behavior, and mood.

Tune in at 7 PM this Sunday evening on KBVR 88.7 or stream online to hear more about her research and how she ended up here at OSU!