Dams, bears, and anglers aren’t the only challenges that salmon face as they undergo their journeys from their mountain river birthplaces to the Pacific Ocean and back again. Timber harvests, dam-induced streamflow changes, and climate change have increased stream temperatures throughout the Pacific Northwest. Native cold-water-loving species like salmon and trout struggle in warm water, while certain parasitic microbes flourish.

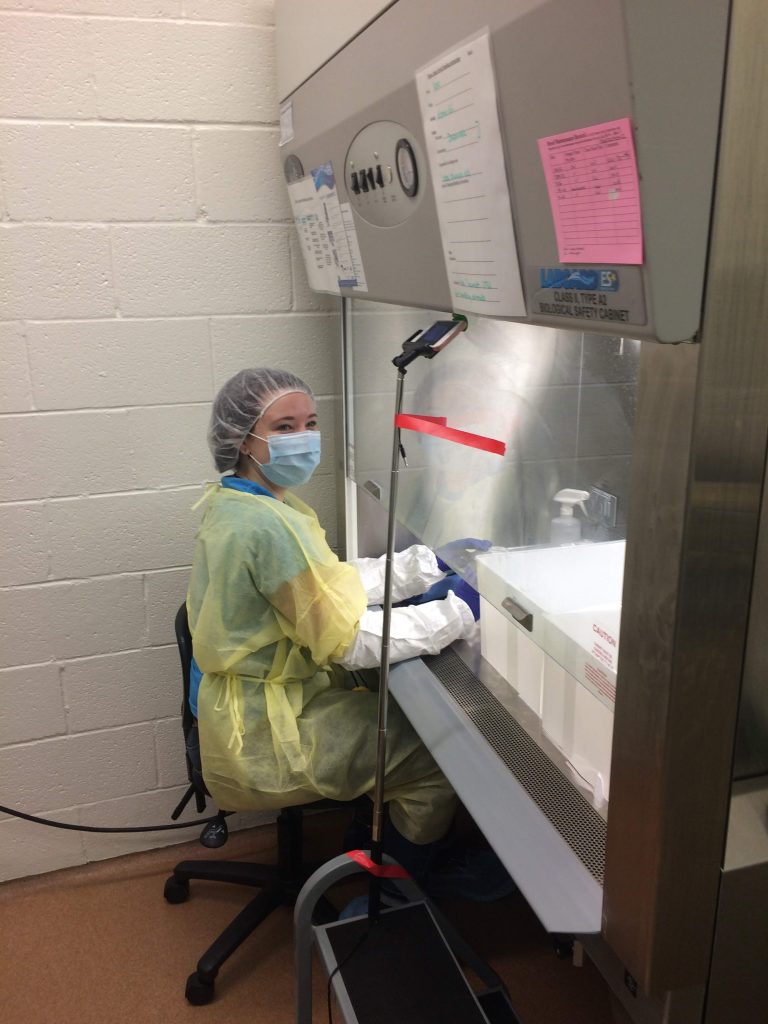

Sofiya Yusova, a master’s degree candidate in the Department of Microbiology at Oregon State University, researches the microbe Ceratonova shasta. Her work aims to understand how C. shasta adapts to climate change in river ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest. Her advisor, Dr. Jerri Bartholomew, runs a long-term monitoring project in the Klamath River, and recently began applying the same methods to the Deschutes and Willamette Rivers. Dr. Bartholomew and her lab identified the complex lifecycle of the parasite, recognizing that C. shasta requires an intermediate host (the polychaete worm) in order to infect fish. Understanding the lifecycle is critical for understanding how to intervene when fish populations are struggling, as well as for anticipating the effects of climate change. As stated on Dr. Bartholomew’s website, “Climate change is expected to have profound effects on host-pathogen interactions. We are examining how this might affect myxozoan disease by developing predictions for how the phenology of parasite life cycles will change under future climates, how changing flow dynamics will alter disease, and to identify river habitats that should be protected as refugia.”

Having a healthy population of salmon is important for many groups, including tribal communities, commercial and recreational anglers. Salmonids (a family of fish including salmon, trout, whitefish, and char) are particularly susceptible to infection when water temperature is warmer than usual, stream flow is low, or the number of C. shasta spores is high. Collaborative monitoring projects on the Klamath River and the Deschutes River have shown that the danger of deadly infections varies along the course of the river. This knowledge has allowed river managers to focus their efforts. For example, if the number of infectious spores is especially high, dam flowthrough rates can be increased to “flush out” the pathogens.

Tune in Sunday, February 2nd at 7pm on 88.7 FM or online to learn more about Sofiya’s research and her personal journey.