Ashlee M. C. Foster, MSEd | Instructional Design Specialist | Oregon State University Ecampus

Whether a pedagogical approach is affirmed by research and/or practical evidence intentional design and effective deployment of pedagogical strategies are essential. We will begin with an exploration of evidence-based design components, which build upon the characteristics of Project-based Learning (PjBL), as discussed in Project-based Learning (Part 1) – Architecture for Authenticity.

Getting Started

Begin with the end in mind. Take a moment to establish the outcomes, goals, and real-world connections that will underpin the project. Consider using the following elements as your guide.

- Identify the Course Learning Outcomes (CLO) students should be able to demonstrate upon successful completion of the course

- Identify the intended project outcomes and the alignment to the course learning outcomes

- Identify skills students will practice and master while engaging with the project

- Articulate the purpose of the project within the contexts of the course, academic program, field of study, and profession

- Articulate authentic connections between the project, across academic disciplines, and professional practice

- Connect the project to an authentic purpose that extends beyond the confines of the course

Course Design Elements

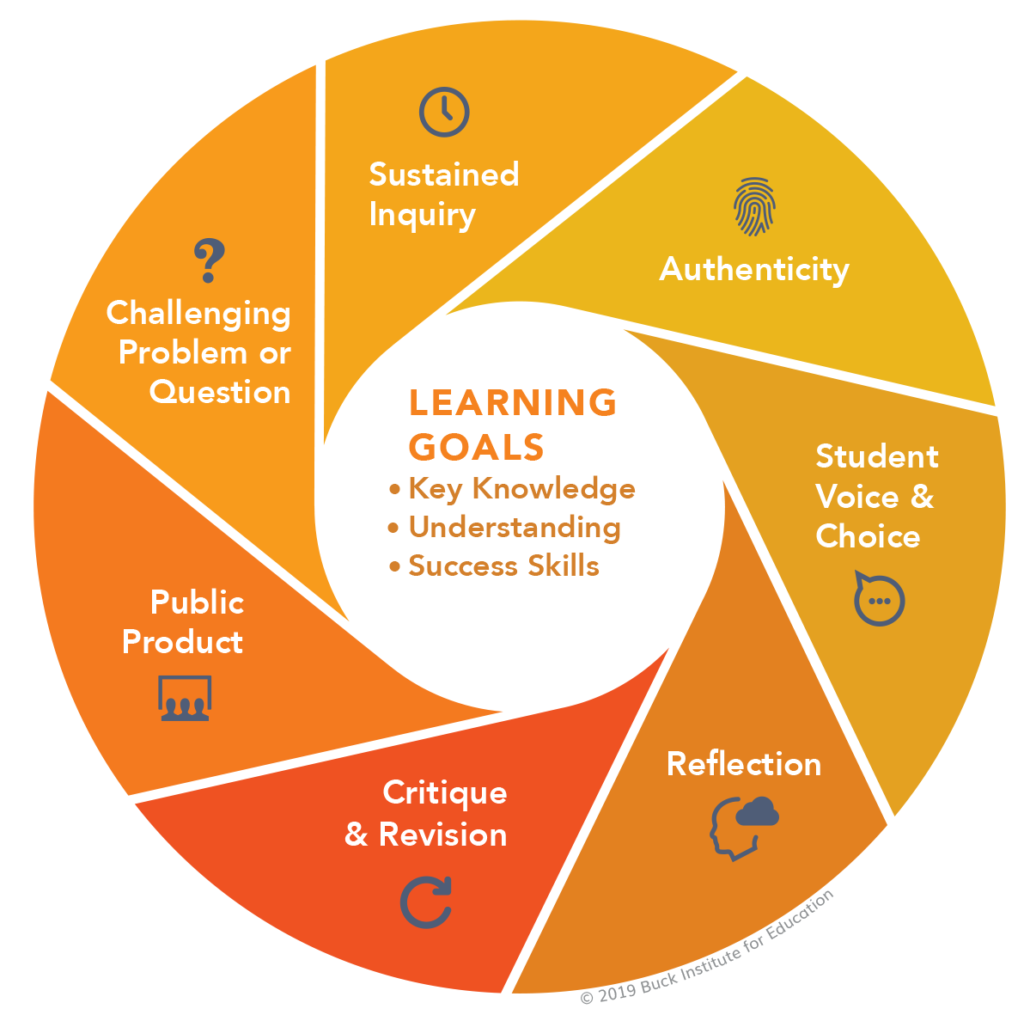

Next, reflect on how you can design your project to incorporate most of the following PjBL core design elements.

Image credit: Gold Standard Project Based Learning by PBLWorks is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Authentic Challenge

Initially, consider creating an opportunity for students to self-select a challenge. This can be anything from finding a solution to existing problems, a remedy for historical barriers, answers for disciplinary relevant questions, or asking new questions. Whatever the challenge may be, a best practice is to contextualize it within a real-world context. Affirm student voice and choice by explicitly sharing how the project connects to the academic discipline, professional field of practice, and real issues by providing feedback. Lastly, help students to see how they can connect the challenge to themselves.

Authentic Product

Development of an artifact that is relevant, timely, impactful, and piques personal interest help to bridge the concepts to the real world. To effectively create an artifact that produces a public good, students should engage in an iterative process that includes: planning, prototyping, seeking and applying feedback from diverse stakeholders (i.e., public, target audience, instructor, peers, Subject Matter Expert), personal reflection, and revisions. To determine whether your project is authentic, consider whether the product(s) create a lasting and meaningful impact beyond the classroom. Examples of authentic products could include a business plan to innovate an existing accessibility tool, a podcast to share about (DEI) Diversity Equity and Inclusion practices or to generate oral histories (i.e., audio interviews) of underrepresented populations.

Sustained Inquiry

Incorporation of formal and informal opportunities for students to question, research, gather information, conduct analysis, apply new knowledge, generate additional inquiries, and highlight evidence is key to the design. These opportunities should be integrated into the architecture of the project, but the actions should be student-driven. This strategy will help promote knowledge construction.

Student Autonomy

Create varied opportunities for students to make their own choices, both collectively and individually. Student-driven choice can extend to such elements as question development, selection of public a product, identification of target audiences, establishment of collaboration protocols, application of knowledge and feedback, and prototype revision methods. Doing so situates students as the diver of their own learning process and creates space for students to hone their metacognitive skills (i.e., self-regulation, monitoring, and self-directed learning).

Reflection

Due to its roots in constructivism, reflection is commonly used in PjBL. Reflection is used as a strategy to foster deep learning, personal ownership of learning, assimilation of new knowledge, integration of lived experiences, effective inquiry, assessment of quality, and the navigation of challenges. While serving as a guide on the side, consider integrating activities to foster ongoing reflection of critical questions. Such questions may include:

- What is known?

- What needs to be known?

- What evidence exists?

- Will the product have an impact on the world outside of the course? How?

- Do I/we bring any personal biases to the project which impacts the design of the product?

- Does the design of the product represent the diversity of the target audiences?

- What works or does not work? Why?

- How can the product be improved? What is the rationale behind the recommended changes?

- How can the quality and efficacy of the product be tested?

- Does the project extend on what the academic domain and professional field have established? If not, how can the project be modified to contribute additional knowledge or insights?

- How does the project connect to my life, my lived experiences, and that of others?

- How will the project help me to develop my professional skills?

An example of a PjBL reflective activity is a design journal. Design journals can include text, visualization, and media elements. Each entry can be structured to cover the following: knowledge gained, ideas, sustained inquiry (i.e., questions, additional research needed), the rationale for product changes, and next steps.

Critique & Revision

Integrating activities, such as a design journal, provides students the opportunity to actively critique, revise, and obtain feedback throughout the duration of the project. There is a multitude of scenarios that may call for critique. Students may find their initial idea to be too broad or specific. The original line of inquiry may have been faulty. One may find the product does not generate the intended public good or service. Therefore, revising the goal and creating a new product may be necessary. Alternatively, situations can arise where students learn of a product’s unintended harm, so a new prototype may need to be created. The goal is to create a course climate that is psychologically safe enough to encourage iteration.

Success Tips

Please note that these best practices and design elements offer a framework. Your course is unique. There is an unending list of potential factors that can impact the design of your course and project (e.g., accreditation, professional competencies, academic rigor, program outcomes, administrative expectations, etc.).

- Keep in mind that you do not have to incorporate everything and the kitchen sink. Take what you can from existing literature, practitioner testimonials, industry needs, professional practices, real-world examples, and lessons learned from your own lived experiences.

- Begin with small additions to your course, assess the impact of those changes, and revise as you deem appropriate.

- Remember that nothing will be perfect, and there are always opportunities to improve. Design with the best fit in mind!

Looking Ahead!

You are cordially invited to revisit the Ecampus Course Development and Training Blog for Project-based Learning (Part 3) – Practical Preparation. In the final installment of this series, we will explore additional project-based learning activities, identify opportunities to integrate technology and examine actual project samples.

References

- Almulla. (2020). The Effectiveness of the Project-Based Learning (PBL) Approach as a Way to Engage Students in Learning. SAGE Open, 10(3)

- Budhai, S. (2016, January 29). Designing Effective Team Projects in Online Courses [blog]. Faculty Focus.

- Chen, & Yang, Y.-C. (2019). Revisiting the effects of project-based learning on students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis investigating moderators. Educational Research Review, 26, 71–81.

- Gold Standard PBL: Essential Project Design Elements. (n.d.). Buck Institute for Education.

- Grossman, Dean, C. G. P., Kavanagh, S. S., & Herrmann, Z. (2019). Preparing teachers for project-based teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(7), 43–48.

- Guo, Saab, N., Post, L. S., & Admiraal, W. (2020). A review of project-based learning in higher education: Student outcomes and measures. International Journal of Educational Research, 102, 101586.

- Larmer, J. (2012) PBL: What Does it Take for a Project to be ‘Authentic’? Edutopia

- Lewis, R., Gerber, E. M., Carlson, S. E., & Easterday, M. W. (2019). Opportunities for educational innovations in authentic project-based learning: understanding instructor perceived challenges to design for adoption. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(4), 953–982.

- Morgan, T. (2019). Enabling Meaningful Reflection Within Project-Based-Learning in Engineering Design Education. In Design Education Today (pp. 61–90). Springer International Publishing.

- Product Toolkits: Scaffolding Guides for Authentic PBL Products. (2012) Buck Institute of Education.

- Project Design Rubric. (2015). Buck Institute of Education. Retrieved from: https://www.bie.org/object/document/project_design_rubric