Your garden soil contains millions to billions of individual microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea, representing tens of thousands of different microbial species. Humans evolved for millenia in the presence of these environmental microbes associated with vegetation, soil, water, and wildlife. Our immune systems are not only adapted to coexist with the majority of these microbes, but may even require that interaction to function properly. Emerging scientific evidence suggests that exposure to soil microbes trains the immune system, reduces inflammation, and improves mental health (Rook, 2013). For example, the common soil bacterium Mycobacterium vaccae has been found to have positive impacts on stress tolerance and mental health (Matthews and Jenks, 2013), while other research has shown that children exposed to greater microbial diversity, such as that encountered in farming environments, tend to have lower prevalence of autoimmune disorders, including allergies and asthma, than their urban counterparts (Hanski et al., 2012).

The primary goal of the Garden(er) Microbiome Project was to understand how much microbial transfer from soil to skin occurs during gardening activities, what types of microorganisms are transferred, and how long they can persist on the skin. We are also interested in exploring how soil microbial communities vary with different management practices (e.g., organic vs. conventional) and geographic locations, as we know that microbes play critical roles in soil nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, pollutant degradation, and, of course, crop health.

To accomplish this study, we recruited 40 gardeners to collect microbial samples from their garden soil and from the surface of their skin (hands). All samples were collected in July–September, 2020, and were equally distributed between the Willamette Valley and High Desert regions, as well as between self-reported organic and non-organic management practices. Each volunteer was asked to collect soil samples from three different garden beds and skin microbiome swabs before, after, ~12 hours after, and 24 hours after gardening (Figure 1). To identify bacterial taxa (different types of bacteria) present in the samples, we used Earth Microbiome Project protocols to sequence the V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene.

Preliminary results

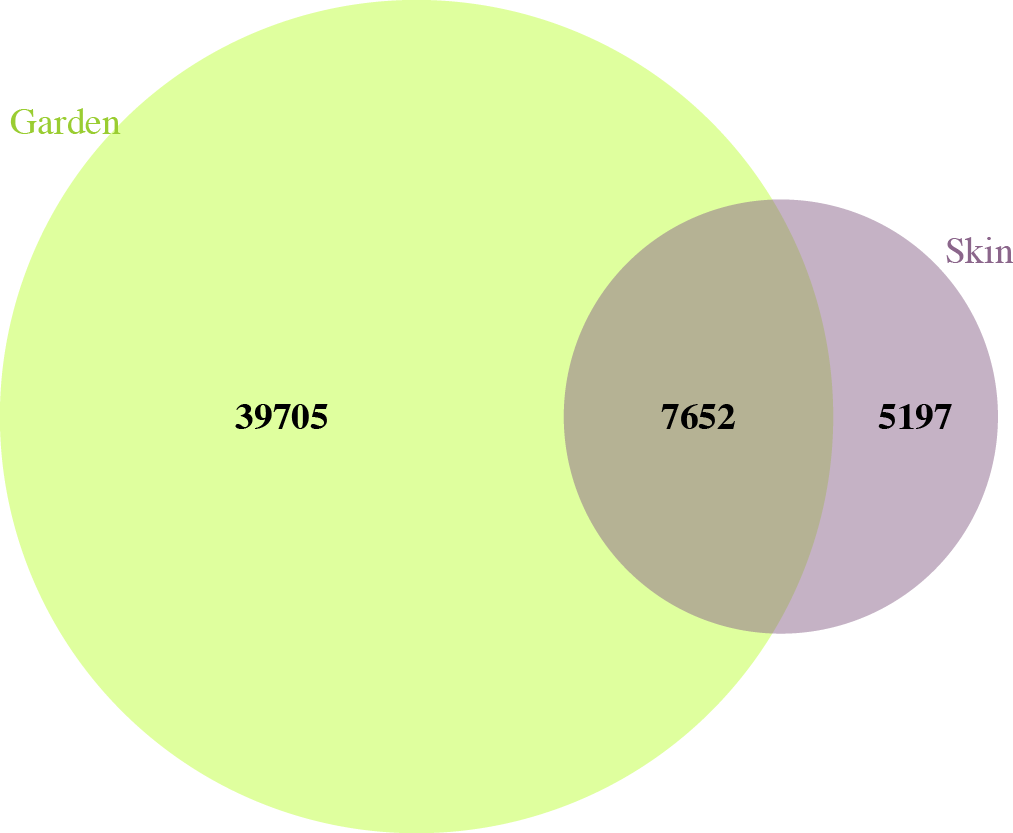

In garden soil samples, we observed over 8.5 million individual bacteria, representing about 45,000 different bacterial species. In skin microbiome samples, we observed over 6 million individual bacteria, representing almost 13,000 different bacterial species. Of all these bacterial species, there were just over 7,500 that were shared between garden soils and gardeners’ skin microbiomes over the course of the study (Figure 2).

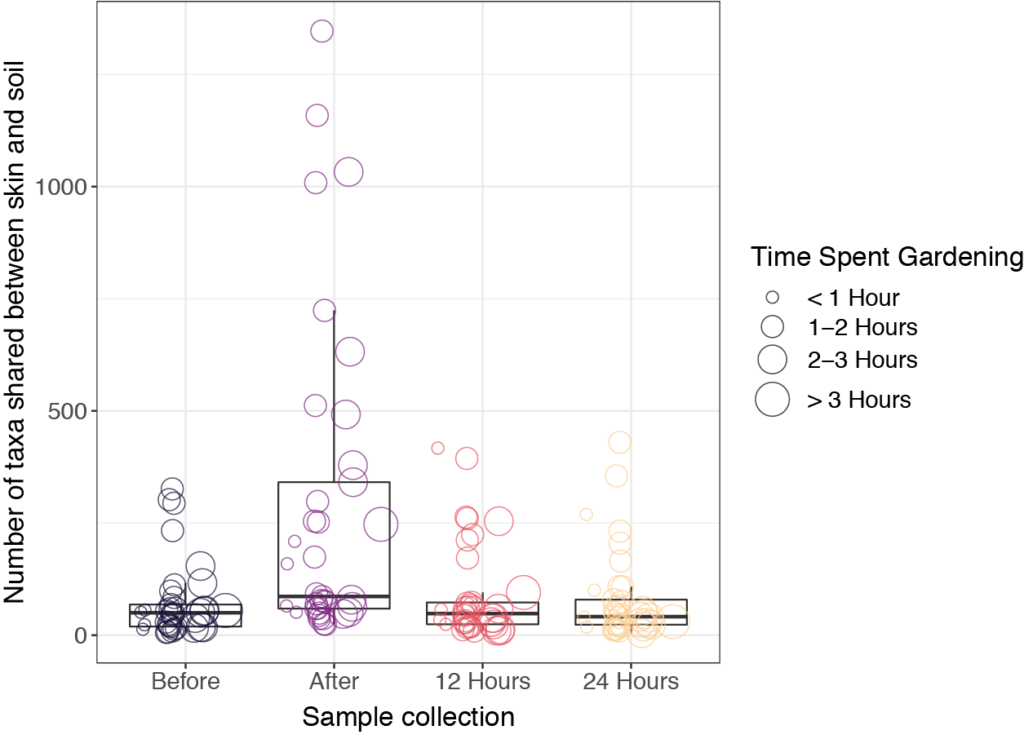

Our initial hypothesis was that skin microbiome samples would be more similar to soil samples immediately after gardening, due to microbial transfer from soil to skin during direct contact. We also expected that the skin microbiome would return to baseline (before gardening) after a period of time, depending on individual behaviors, such as washing hands and bathing. It turned out that soil microbial communities were very different than those found on skin. Interestingly, skin microbiome samples tended to be dominated by a small number of taxa, though they were not always the same taxa at different sampling times. For many of the study participants, we did indeed see an increase in shared taxa for the skin samples collected immediately after gardening (Figure 3). However, soil microbes were generally transient on the skin and were no longer present after 12 hours. We note that the COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced hand-washing behaviors and use of hand sanitizers, which could have had additional unexpected impacts on the skin microbiome.

Though it was beyond the scope of the project to describe life history details about every type of bacteria that was found, we did investigate a handful of taxa that were highly abundant in many samples. In garden soil, many of the most abundant bacteria belonged to the genus Pseudomonas. In a recent paper, Sah and Singh (2016) state, “The genus Pseudomonas encompasses arguably one of the most complex, diverse, and ecologically significant group of bacteria on the planet. Members of the genus are found in large numbers in all the major natural environments (terrestrial, freshwater, and marine) and also form intimate associations with plants and animals.” Importantly for gardens, several species of Pseudomonas are able to promote plant growth, while others are well-known plant pathogens. Members of the genus Sphingomonas were also common soil inhabitants found in this study. Sphingomonads are broadly distributed in the environment, including soil, water, air, and plant leaves. Only one species of Sphingomonas is known to cause disease in humans, typically in hospital-acquired infections (Balkwill et al., 2006). A third genus of interest from garden soils was Streptomyces. This is a large genus with over 500 members that are ubiquitous in soils. They are known to form symbiotic relationships with plants and animals, and they are responsible for the production of over 2/3 of all known antibiotics (Antoraz et al., 2015). Streptomyces also produce the chemical compound geosmin, which gives soil its earthy smell (Seipke et al., 2012).

The composition of skin microbiome samples in this study varied wildly from individual to individual, and sometimes even for the same individual at different time points. Among the most abundant taxa we found were members of the genera Pantoea, Acinetobacter, Bacillus, and Klebsiella, as well as Pseudomonas, which was described above. Generally speaking, these are very diverse genera and are widespread in many environments, including soil and human skin. Some Pantoea species produce antimicrobial compounds that can help control fire blight in fruit trees (Walterson and Stavrinides, 2015). The genus Acinetobacter contains two species of interest for health reasons—A. baumannii is typically found in wet environments and is a notable opportunistic pathogen associated with hospital-acquired infections (Howard et al., 2012), whereas exposure to environmental sources of A. lwoffii is thought to protect against development of allergies, although it can also cause infection in immunocompromised individuals (Debarry et al., 2007). Members of the genus Bacillus have been explored for potential probiotics (Elshaghabee et al., 2017), and the genus Klebsiella is somewhat notorious for its human pathogenic members. However, Klebsiella, Pantoea, and several other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family have highly similar DNA sequences in the region that we targeted, so these composition results should be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusion

This study represents one of the very first investigations of garden soil microbiomes and, to our knowledge, the only one that explores the ability of soil microbes to transfer and persist on human skin after typical gardening activities. Overall, we found that garden soils tend to have far greater bacterial diversity than skin microbiome samples. Bacterial community composition was largely similar across different garden beds, whereas skin microbiome composition varied dramatically. Some soil microbes appeared to transfer onto skin during direct contact with soil, but they were generally gone within 12 hours, suggesting a low ability to permanently colonize skin. However, a daily gardening routine with repeated and extended contact with soil likely reinoculates the skin such that soil microbes are like a regular visitor during the growing season.

The specific ecological role of most microbes, both in soil and on skin, is a relatively new area of investigation garnering intense interest. However, few, if any, concrete recommendations are currently available to guide actions towards improving plant and human health. A primary goal of this study is to gather baseline data for future studies, which are needed to further explore the impact of daily soil contact over longer time periods (e.g. entire growing season), how changes in gardeners’ skin microbiomes compare with non-gardeners, and whether consumption of fresh garden produce affects the gut microbiome.

Aaron recently surveyed gardeners, to ask their opinion on the aesthetics of his study plants. A quick look at the results suggests that gardeners and bees might be attracted to different flowering plants. While Gilia capitata was the most visited plant in Aaron’s study plots, it was ranked 6th most attractive (out of 27 plants) by gardeners. The story gets worse for Madia elegans (2nd with bees, 20th with gardeners), Aster subspicatus (3rd with bees, 14th with gardeners), and Solidago candensis (4th with bees, 23rd with gardeners).

Aaron recently surveyed gardeners, to ask their opinion on the aesthetics of his study plants. A quick look at the results suggests that gardeners and bees might be attracted to different flowering plants. While Gilia capitata was the most visited plant in Aaron’s study plots, it was ranked 6th most attractive (out of 27 plants) by gardeners. The story gets worse for Madia elegans (2nd with bees, 20th with gardeners), Aster subspicatus (3rd with bees, 14th with gardeners), and Solidago candensis (4th with bees, 23rd with gardeners).

We are soliciting Master Gardener feedback on the attractiveness of the native wildflowers that Aaron Anderson is studying for pollinator plantings. More detail on the study can be found at:

We are soliciting Master Gardener feedback on the attractiveness of the native wildflowers that Aaron Anderson is studying for pollinator plantings. More detail on the study can be found at: