Natives Plants & Native Cultivars Recent studies report an increase in consumer demand for native plants, largely due to their benefits to bees and other pollinators. This interest has provided the nursery industry with an interesting labelling opportunity. If you walk into a large garden center, you find many plant pots labelled as “native” or “pollinator friendly”. Some of these plants include cultivated varieties of wild native plant species, or native cultivars, sometimes referred to as “nativars”. While many studies confirm the value of native plants to pollinators, we do not yet understand if native cultivars provide the same resources to their visitors.

Echinacea purpurea

Photo Source: Moxfyre – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

E. purpurea ‘Maxima’

Photo Source: Ulf Eliasson – Own work, CC BY 2.5,

E. purpurea ‘Secret Passion’

Photo source: National Guarden Bureau

An Echinacea Example Above are three purple cone flower (Echinacea purpurea) plants: on the top is the wild type, in the middle is a native cultivar ‘Maxima’, and on the bottom is another native cultivar ‘Secret Passion’. In some cases, like ‘Secret Passion’s double flower, there is an obvious difference between a native cultivar and a wild type that might make it less attractive to insect visitors. Since we can’t see the disc flowers (the tiny flowers in the center of daisy family plants), we might assume that ‘Secret Passion’ may be more difficult for pollinators to visit. The floral traits displayed by ‘Maxima’ seem similar to the wild type, but it might produce less pollen or nectar, causing bees to pass over it.

Unless we observe pollinator visitation and measure floral traits and nectar, we can’t assume that native plants and native cultivars are equal in their value to pollinators.

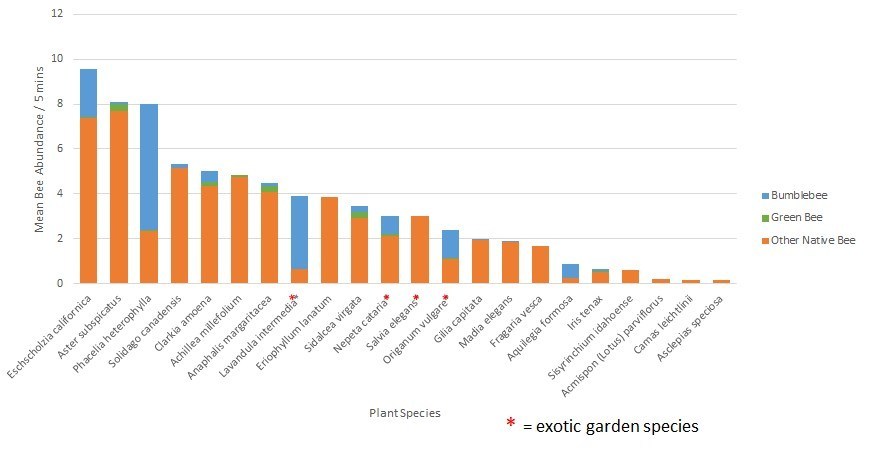

Native Cultivar Research One study looking at the difference between native species and their cultivar counterparts has come out of the University of Vermont (my alma mater!). A citizen science effort started by the Chicago Botanic Garden is also currently ongoing. My Master’s thesis will be the first to use a sample of plants specific to the Pacific Northwest. We have selected 8 plants that are native to Oregon’s Willamette Valley and had 1-2 native cultivars available. These plants have shown a range of attractiveness to pollinators (low, medium, or high) based on Aaron’s research. We are including plants with low attractiveness because it’s possible that a native cultivar may have a characteristic that makes it more attractive, such as a larger flower or higher nectar content.

Experimental Design We have four garden beds in our study, and each bed contains at least one planting of each native species and their cultivar counterpart(s). This kind of design is called a “Randomized Complete Block” (RCB). The RCB has two main components: “blocks”, which in our case are garden beds, and “treatments”, which are our different plant species. Above I have drawn a simplified RCB using two of our plants: Camas and California poppy. The bamboo stakes outline each plot and have attached metal tags that label the plants.

We planted our seeds and bulbs in November and will plant out 4″ starts of the other plants in early Spring. Look out for my spring and summer updates to see how these plots progress from mulch and bamboo stakes to four garden beds full of flowers and buzzing insects!

Reference articles: https://www.asla.org/NewsReleaseDetails.aspx?id=53135 http://www.gardenmediagroup.com/garden-media-releases-2019-garden-trends-report