In the recent blog post “The Controversy Surrounding ‘No Mow May”, Dr. Langellotto explores the lack of good science supporting the idea of giving your lawn a month-long break from being mowed. Despite the scientific controversy, “No-mow May” is an idea that has taken off. It is simple and makes people feel good about helping pollinators, while also doing less yard work. At its best, it may indeed work in some places, for some people, to help some pollinators for a month…but what about the rest of the year?

A month of neglecting your lawn might allow flowers to bloom, depending on what grows in your lawn besides grass. These may well attract pollinators – but the untended expanse may also fool various creatures into thinking they have a safe place to nest, pupate, and burrow. What happens to them when the mowing starts again? Bees and butterflies can fly away to other flowers, but less-mobile creatures may be killed or displaced.

It’s also questionable whether this method reduces yard work at all. A lawn grown long and lush in peak growing season – and which may be wet from spring rains as well – will be very difficult to mow after a month. So at best, “No-mow May” provides a very short-term benefit, and may cause more problems than it solves.

Are there other routes to a low-maintenance pollinator paradise?

Definitely! As Gail concluded, a pollinator garden provides year-round support to pollinators, without the disruption of intermittent mowing. If you want detailed information on creating a pollinator garden in the PNW, and what to plant in it, here’s a good resource to get you started: “Enhancing Urban and Suburban Landscapes to Protect Pollinators”, https://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/pub/em-9289-enhancing-urban-suburban-landscapes-protect-pollinators.

But maybe you aren’t able to devote a whole garden to pollinators. Maybe you just have a little bit of space. How about planting just a few strategic plants?

Certain types of plants are pollinator powerhouses. They tend to attract a wide variety of pollinators. Some are food plants for many different native butterfly and moth caterpillars. The best bloom for a long time, offering their bounty for up to several months. To extend the bloom season even more, plant several varieties of the same species, with varying bloom times, or multiple related species.

Include a few of these in any landscape and you will benefit many pollinators. Choose natives when you can, and choose at least one species from each family or general category.

Pollinator Powerhouse starter list

In western Oregon, you could do worse than start with the Garden Ecology Lab’s Top 10 Oregon Native Plants for Pollinators (https://blogs.oregonstate.edu/gardenecologylab/category/top-10-plants-for-pollinators/) and their relatives. (Top-10 are in bold below).

Aster family (Asteraceae) – Daisies or Composites.

A huge family with many pollinator favorites. Here are just a few.

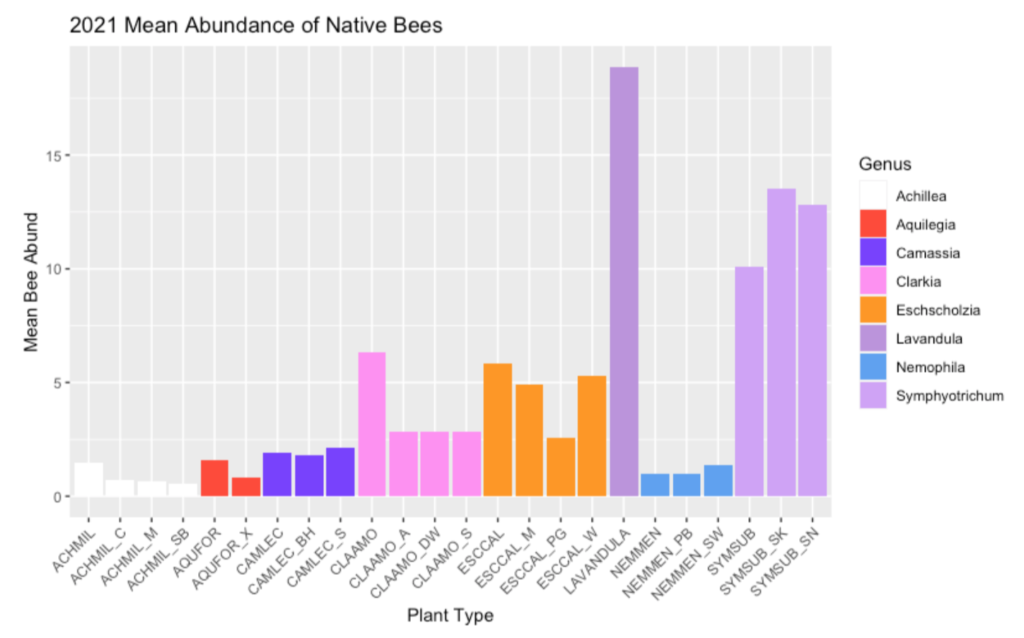

Achillea millefolium (yarrow)

Anaphalis margaritacea (pearly everlasting) NOT for a well-fed and watered area, or it can become invasive

Eriophyllum lanatum (Common woolly sunflower)

Solidago spp. (goldenrod) – Plant Native S. canadensis (Canada goldenrod), miniature S. ‘Little Lemon’, and late and showy S. ‘Fireworks’ for a really long season of bloom! Be aware that most tend to spread by seed, and the birds won’t eat all the seed. Seedlings are easy to pull, though, if you don’t want too many.

Symphyotrichum/Aster – Tall native S. subspicatum (Douglas aster) or short native S. hallii (Hall’s aster), miniature S. ‘Woods Blue’, and many others.

Also: Echinacea (coneflower), Erigeron (fleabane), Helenium (sneezeweed – for treating sneezes, not causing them), Helianthus (perennial sunflowers), Inula, and many more.

Mint family (Lamiaceae)

Another really big family almost universally attractive to pollinators. Includes Agastache spp. (anise hyssop, hummingbird mint), Calamintha nepeta (calamint), Caryopteris x incana (bluebeard – a small shrub), Monarda didyma (bee balm), Salvias, and herbs rosemary, mint, basil, oregano, and thyme, among others.

Sedum/Hylotelephium (stonecrops)

Both the low groundcover Sedums and the tall, fall-blooming Hylotelephiums like ‘Autumn Joy’ are pollinator magnets , though often you will only see honeybees mobbing them.

Alliums – Any kind

There are spring, summer and fall bloomers – plant some of each, mixed in with other pollinator plants. Late spring to summer is the main Allium season, with dozens of kinds available. For late summer and fall try Allium tuberosum (Garlic Chives), Allium cernuum (nodding onion), a NW native, and Allium thunbergii ‘Ozawa’ (Ozawa Japanese onion) for the very end of autumn.

Self-sowing annuals

Many annuals will bloom straight through the season until frost.

Alyssum, Clarkia amoena (Farewell-to-spring), Eschscholzia californica (California poppy) (mostly annual), Fagopyrum esculentum (Buckwheat) – a great cover crop, pollinators love it, and you can harvest the seeds to eat or let it self-sow; Gilia capitata (globe gilia), Limnanthes douglasii (NW native), Madia elegans (common madia), Phacelia heterophylla (Varileaf phacelia).

To make sure your pollinator powerhouse plants thrive and bloom for a long time, make sure to give them good growing conditions.

• Soil should be reasonably good (though not excessively fertilized, which can cause pest-attracting lush growth and fewer flowers).

• They should have full to half-day sun in most areas.

• Even native plants appreciate some water during dry summer months, otherwise they will go dormant.

• Grouping these plants together can make care easier – voila, a pollinator garden! – but they can be tucked into any available spot as long as their needs are met. Even a vegetable garden!