What is the Portland Bee Guide?

This month has seen the release of the Portland Bee Guide! This guide was a collaborative project among many different members of the Garden Ecology Lab, along with numerous others inside and outside Oregon State University. Our goal for the project was relatively simple: create an accessible guide to Portland bees. If you haven’t already, click here to download the Portland Bee Guide. It contains species descriptions of 67 bee species found in Portland, OR, gardens (including the ones seen below!), and the accompanying iNaturalist guide (click here) contains photos and interactive functional trait filters for each species. Read on for bonus content, not included in the bee guide or in the social media campaign we ran to promote the guide earlier in recent weeks.

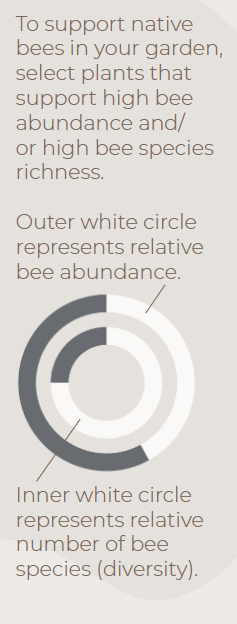

This blog will also serve as an access point to the social media content, for those not on Instagram or Facebook. The social media campaign contained three sets of posts: one focused on floral resources for bees, another on nesting sites for bees, and the final was a feature of some of the Portland bee-friendly gardeners.

Making the Guide

Most of my time spent on the guide happened in my home, which is my preferred work space (it helps that a cat is included). Specifically, a table on the same back patio where I grew up spending time with my family in the outdoors as I was growing up. When I entered graduate school, the sampling in Portland gardens was already finished—so many people had contributed to this project before I ever knew it existed. The main thing that inspired me to work in science communication was the opportunity to serve as a liaison between the academic sphere and the public sphere. I’ve always enjoyed interacting with people, and was parented by scientists who valued their work in Extension programs.

The back patio, where I spent much of my time this past summer working on the bee guide.

Because so much of my work took place on my computer, far removed from the soil, forage, and buzzing bees of Portland, I knew I wanted to make visiting some of the gardens a priority. This would allow me to have a deeper understanding of the guide itself prior to its release, as well as to take photographs and interview some of the gardeners who hosted diverse bee communities in their backyard. I completed my visits in June 2023, and got a chance to talk with gardeners about their successes, setbacks, motivations, and more. Let’s look at some of these gardens!

Our 3 Featured Gardeners

Pascal: “Small and mighty”

Pascal’s garden is in Northeast Portland. He lives just off a busy street, so his main goal when creating his garden was privacy. I was inspired by Pascal’s eye for design—his garden, to me, was the definition of maximizing space. He has created a layered effect, with winding pathways, designated sections for food crops and ornamental plantings, but everything blended seamlessly. Though I could tell from the road that Pascal’s garden was going to be quite something, while I was inside it felt like I was in on a secret: here I was, in a secluded refuge.

I asked Pascal!

What is the biggest challenge you deal with in your garden? “My biggest challenge is keeping the garden healthy and thriving during dry stretches of weather, which seem to be getting longer each year. I use soaker hoses throughout the garden and run them once a week, but during extreme heat and dry weather over the last few summers, the stress on the plants is obvious. I’m now running them more often, and this year, earlier than in previous years. More water means a bigger water bill, but it’s better than losing established plants to drought. When I do lose plants, I now plant replacements that are native and more drought tolerant.”

What has been your biggest gardening success? “My biggest gardening success has been transitioning this yard, that was basically lawn and a few trees, into a biodiversity hotspot with almost 80 species of plants stuffed into a small space. All those plants now provide a lush green wall that blocks out some of the noise and business of our urban location. They also provide shelter and forage year-round for a variety of birds, insects (including pollinators), a few small mammals and even a lost cat, who we were able to rehome.”

What is your favorite spot in the garden? “My favorite spot in the garden is under the canopy created by a series of overlapping trees that create a cool, shaded area over the lawn. It’s the perfect spot to sit on a hot day and face out towards the surrounding gardens and see all the activity that is going on with birds, bees, and other insects moving around. The yard is still noisy, but sitting under those trees feels peaceful.”

Pascal and my father, Neil (also a retired Community Horticulturist for Oregon State), talking about plants in Pascal’s urban refuge. I love this photo because you can get a feel for the layered effect that this garden has. The variety of foliage textures makes the space feel welcoming, cozy, and vibrant.

Bob: “A bee’s urban paradise”

I visited Bob, along with a fellow Master Gardener, Cathy, at the Multnomah County Master Gardeners Demonstration Garden. This garden is open to the public, and Bob made is clear that visitors are welcome. Visitors are free to come walk around the garden, which is not limited to pollinator-oriented spaces. Other gardeners focus on food crops, ornamental plantings—there’s even a willow tunnel to walk under. The garden is beautiful, and worth a stroll-through if you’re in the area. It was such a joy to talk with both of them—their passion for both pollinators and gardening was tangible, and his interest in learning more about the bees he was seeing in his plot was inspiring.

Bob and Cathy standing next to their sign at the Multnomah County Demonstration Garden. If you’re in the Portland area, take a visit! It’s open to the public, and they were both wonderful to talk to.

The number of active pollinators here was astounding! Many of my now-favorite bee photos came from my visit to Bob’s garden. Male long-horned and leaf-cutter bees snoozing inside California poppy, Agapostemon (“green bees”) on Gaillardia, and bumble bees abounded during my midday visit. Many of those bees are pictured in our social media campaign, which will be included below.

I asked Bob!

What is the biggest challenge you deal with in your garden? “Unwanted plants. However, we have developed management strategies to deal with them. We plant very densely and layer plants vertically; we also tolerate some ‘weeds’.”

What has been your biggest gardening success? “Over time, Master Gardener colleagues—some of whom initially looked askance at what we were doing—have come to appreciate the aesthetic of our plantings. While some still wouldn’t garden the way we do, they now recognize that there’s a method to our madness.”

Where is your favorite spot in the garden? “I enjoy standing at the intersection of the steppingstone pathways, where I feel engulfed by vegetation.”

Sherry: “A suburban oasis”

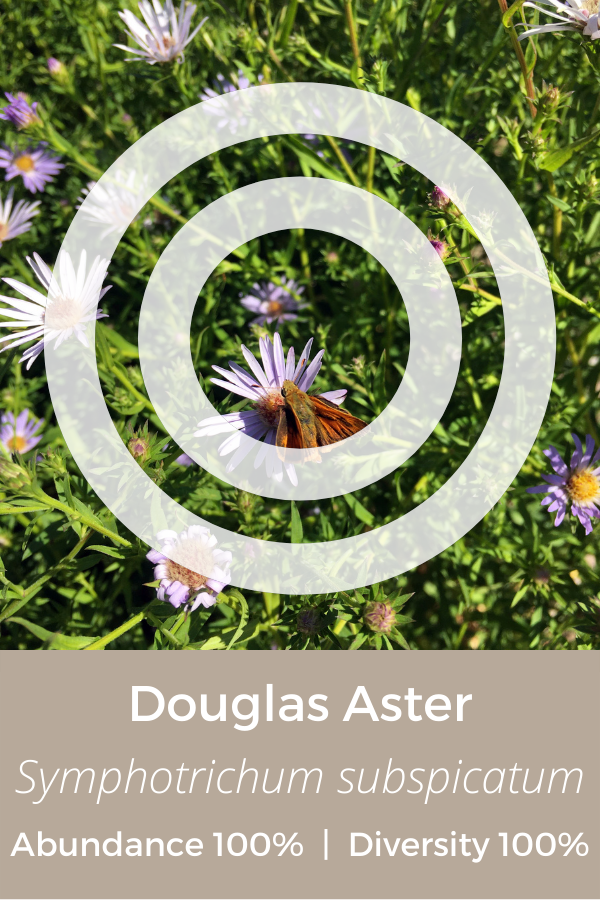

Sherry is a long-time supporter of the lab, and follower of our research. One of my favorite parts of her garden is her planting of Douglas aster and goldenrod, which she was inspired to plant based on Dr. Aaron Anderson’s research, a past GEL lab member. The plating overlooks the Willamette River. I included this quote in the social media campaign, but I can’t help from including it here too: “Growing together, both receive more pollinator visits than they would if they were growing alone. It’s a testable hypothesis; it’s a question of science, a question of art, and a question of beauty.” – Robin Wall Kimmerer, from Braiding Sweetgrass.

Something I admire about Sherry’s garden is how she incorporates both native plants, and also plants that are important or special to her. It reminds me of my childhood garden growing up, planted and cared for by my parents, both horticulturists. I remember being surrounded by vegetation on our back patio, which was one of the first places I ever experienced the natural world up close.

I asked Sherry!

What is the biggest challenge you deal with in your garden? “Leaving unwanted and unmulched ground for nesting bees is hard for me. Bare ground goes against my nature!”

Sherry has done a wonderful job of incorporating more patches of bare soil into her garden: these spots are perfect for ground-nesting bees!

What has been your biggest gardening success? “A bee garden starring Douglas aster and goldenrod, two natives that tested well in the Garden Ecology Lab research. I added Allium, Emerus, rose, Persicaria, Phlox, Verbascum, and a Vitex for diversity and to extend bloom time.”

Where is your favorite spot in your garden? “I favor areas where there is a place to pause and reflect: an alcove off the driveway affords a scene of raised beds against a coral-colored wall, a bench surrounded by a circle of Phlomis offers expansive views of the pollinator garden, and a second-story deck gives a bird’s eye view of colorful shrubs and perennials below.”

Sherry standing next to the Phlomis in her June garden. This is one of her favorite spots to pause and admire the work she has put into this space. I can see why!

Social media content lives here, too!

Above: the set of slides included in our first post, which focused on floral resources for bees.

Above: the set of slides for our second post, which covered nesting sites for bees.

Above: the third and final post in our social media campaign, featuring Portland gardeners Pascal, Bob, and Sherry!

Thank you to everyone who has taken the time to tune in over the past month. Take some downtime during our rainy Oregon winter to familiarize yourself with the written guide PDF (downloadable here) and the online interactive iNaturalist guide (click here), so you’re ready for all our Portland bees next spring!

Do you have questions about the guide? I am more than happy to chat with you! Feel free to reach out to me at nicolecsbell@gmail.com.