Hello gardeners! Taylor Janecek here, PhD graduate student in the Garden Ecology Lab. Earlier this year I created a blog post titled “Meet the Garden Ecology Lab’s New Ph.D. student, Taylor Janecek” introducing myself. In this post, I described my academic and personal background that has led me towards the wonderful world of pollinator ecology and a survey for a summer study. Today, I would like to share the process of that with you all.

Pollinator gardens

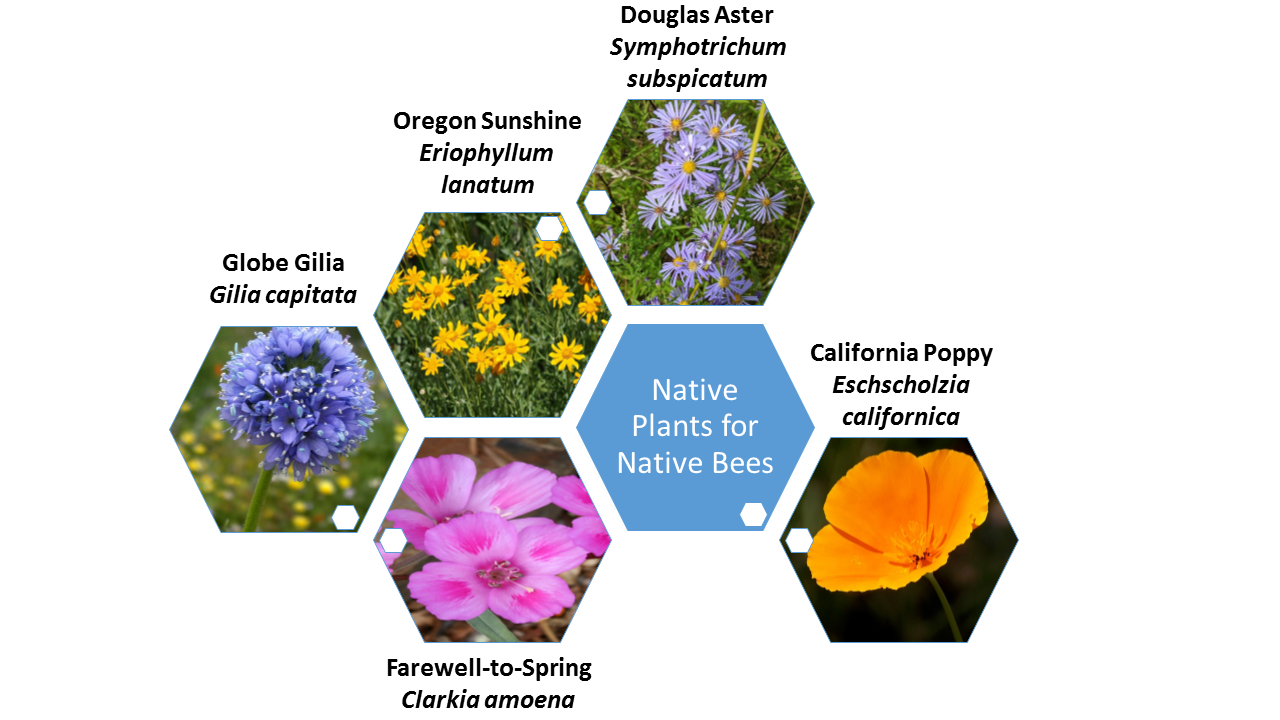

First, I’d like to start with a little bit of examination of pollinator gardens. The basic idea of a pollinator garden is to provide habitat and floral resources for their namesake, while native plant gardens can have more variety in purpose (food/habitat for other wildlife such as birds, for example). However, pollinator gardens and native plant gardens have a lot of overlap, and for many people, mean the same thing.

Research objectives

Gardening for pollinators is an extremely popular activity among gardeners, including in the Pacific Northwest. There have been studies of residential and community garden flora in other areas of the world, with the most detailed information being available for gardens in the United Kingdom1. Some articles highlight gardens in U.S. cities, including Baltimore, Boston, Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis, and Phoenix, though the research is notably less than in the U.K.. However, there have not been any similar studies in the Pacific Northwest or Western Oregon! Our goal is to document the plant community in these pollinator gardens. We are also interested in seeing the types of pollinators that these gardens could support, as well as how gardeners are making decisions on what to plant.

Methodology

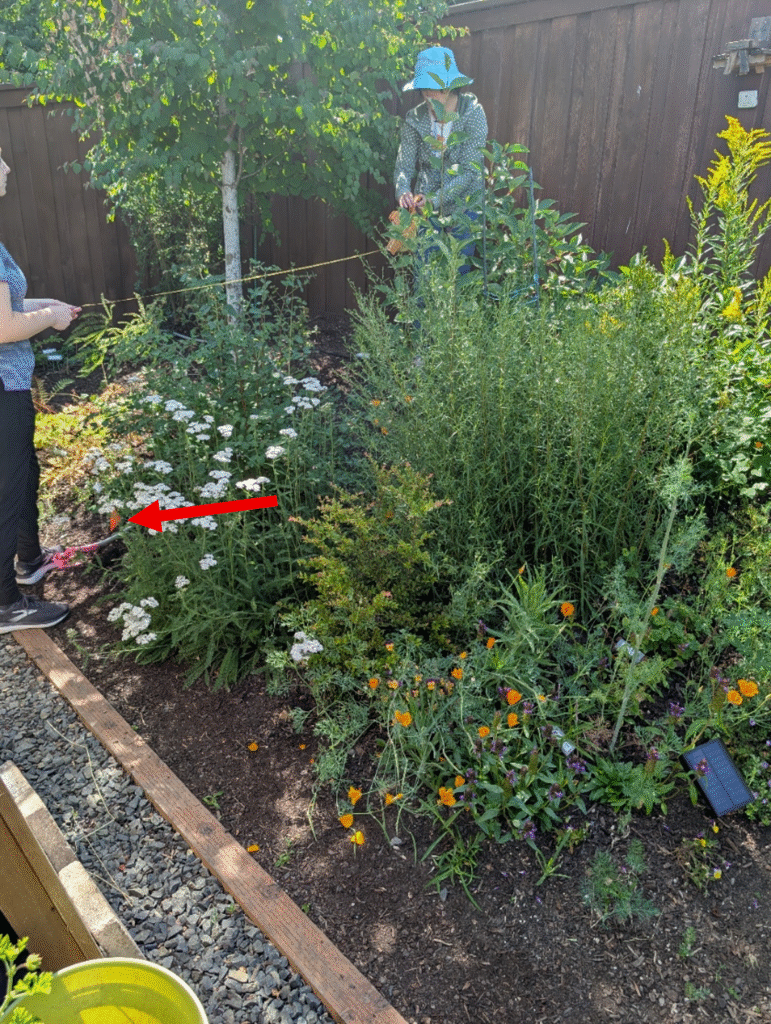

To start this study, we recruited 26 gardeners: 10 in Corvallis/Albany, 6 in Eugene, and 10 in the Portland metro area. We visited one community garden in each city, and the rest of the gardens were residential. As I’m sure you know, gardening can be quite an expressive endeavor, so each garden was unique in many aspects: size, location, planting methodology, etc. Through our survey and my preliminary visits, I asked gardeners to point me to their pollinator garden or, perhaps more accurately, the area dedicated to attracting pollinators.

To start our data collection, I wanted to make sure we had some of our bases covered for analysis later. For this study, that includes measuring the surface area of the pollinator garden. This is similar to Nina’s surface area data collection for her syrphid fly study (I recommend giving that a read!), where we used field measuring tape to collect shape measurements and determine the surface area of the pollinator garden. Sometimes this had to include multiple, easy to measure shapes that we would separate using flagging. Once our surface area was calculated we would begin collecting our floral data.

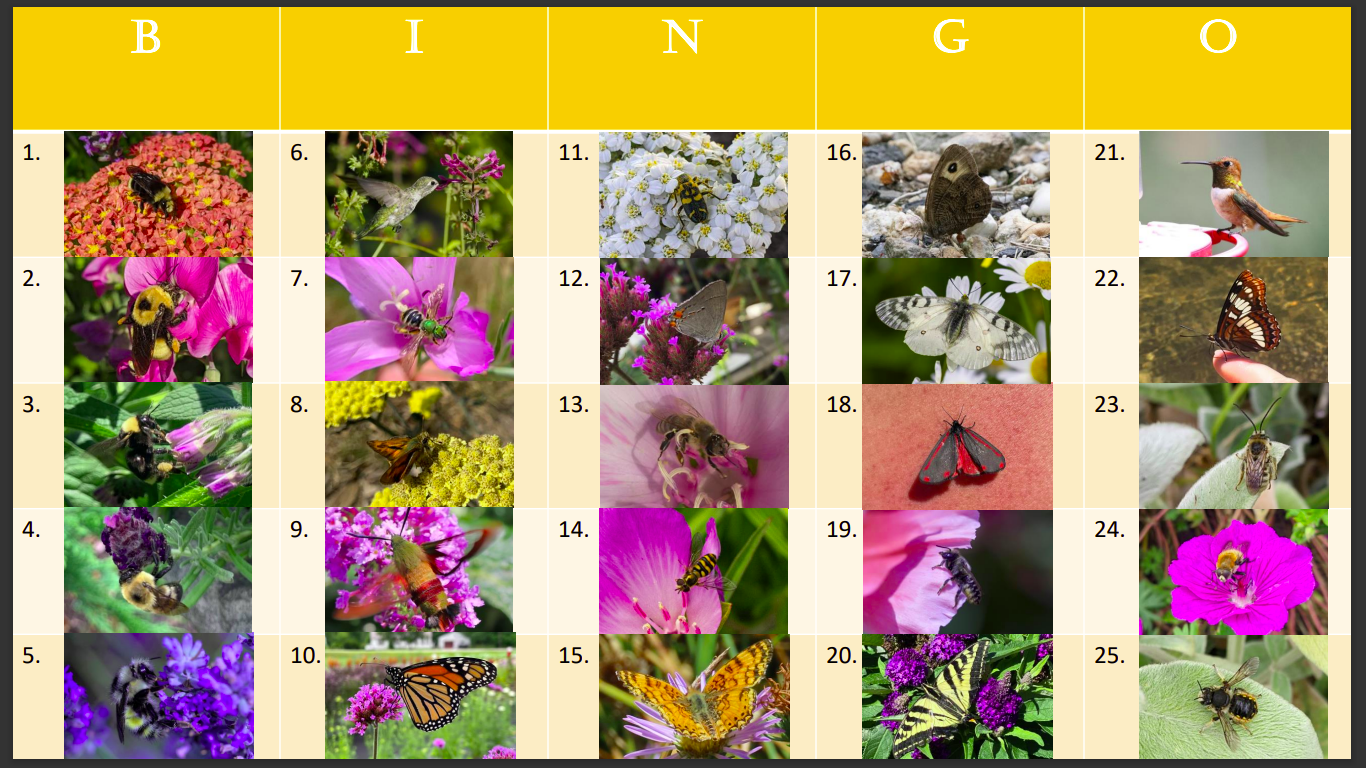

Plants are fascinating organisms, and I’d like to think they’d scoff at us for trying to categorize them into easy to manage boxes. That thought went through my head not only for species identification, but also for collecting abundance data. For plant identification, we would attempt to identify to the genus level in the field. For each unique species at each garden site, we would also take a digital voucher specimen. To take a digital voucher specimen, we would take 3-5 photos of each unique plant per garden site and upload to iNaturalist. We also enabled privacy settings on iNaturalist which made our garden locations hidden. These digital vouchers not only make our data efforts more robust but also allow us to identify and confirm identifications later. Identification of plants to species level can be done through pictures, but it is important to capture important plant traits, and some of those photos could be: whole plant photo, flower, top side of the leaf, underside of leaf, stem and nodes, and sometimes the base of the plants (or any combination of these). Since we were not looking to solely collect data on plants that were in the flowering stage, these vegetative (leaf and stem) characteristics were important to collect. We wanted to capture as much information as possible during our work.

After vouchers were collected for a given plant, abundance data was then collected. What I said earlier about plants not wanting to be contained in easy to manage boxes is particularly true here. There are many ways for collecting plant abundance data, but there was an important consideration of the study. These are not our gardens, we can’t go digging plants up or damaging them, and so our data collection needed to be gentle. We opted to collect “Stems”- meaning we would count the number of stems on a plant emerging from the soil, and “Plants”- where we would count individual plants. Ideally, we would collect both for each plant, but this method was particularly useful when we were counting highly rhizomatous (meaning plants with underground rhizomes which are a type of stem) or clonal plants (meaning the parent plant puts off shoots that creates new, identical plants that remain attached to the parent) such as goldenrod or asters. Knowing where these types of plants begin and where they end would be impossible without actually digging them up, but counting their soil emerging stems works well as a count of abundance for this study. For others, such as avens (genus: Geum), or bulb plants like the Iris, counting individual plants is more informative. There were even times that there was such a high density of plants or stems that we would have to subsample, and if you’re aware of how dense some plants can get (like Douglas Aster), subsampling was a must.

The summer season is over, what’s next?

In total, we have almost 1000 digital vouchers and close to 300 unique plant species for the 26 gardens. The diversity was truly impressive, and there may be even more unique species as we get identification confirmations! We are currently working with the data we collected throughout the summer to calculate a few different community metrics, namely biodiversity, species richness, and abundance. Additionally, we are interested in what kind of pollinators these gardens would likely support. We’d like to examine if these community metrics differ between each city, if they are correlated to each city, and how surface area of these pollinator gardens ties in. We are currently getting our identifications confirmed, and we’re also adding a few more data points that we are curious about. Such as: what was the relative proportion of plants we observed that were native/non-native to our region? What percentage were cultivars? What about edible plants? Did this differ by each city, or did it differ by surface area, or both?

Some of the data we collected was also in the form of survey responses. There are some official pollinator plant lists in other parts of the US, but what about the Pacific Northwest and in our region in particular? We are cataloging pollinator plant lists that gardeners use in the Willamette Valley, and I’m interested in how these sources and recommendations compare to the data we collected in the field and other available pollinator data.

Since we’ve only begun the data analysis process, I don’t have any answers to share with you all just yet. Summer data collection seasons go by very quickly, and there are many steps involved to even be able to launch a project that I did not reflect on in this post, such as survey construction and policy, and preliminary garden visits (among other things). I look forward to diving farther into data analysis and sharing our findings. I hope this was an interesting and informative look into our research and how we collected our data.

One other thing I’d like to note is that we are also planning and preparing a multiyear experiment, and I am excited to share updates on that as it moves forward!

References

1. Loram A, Thompson K, Warren PH, Gaston KJ. Urban domestic gardens (XII): The richness and composition of the flora in five UK cities. Journal of Vegetation Science. 2008 June 1;19(3):321–30.

3 Comments

Add Yours →I found this absolutely fascinating. I wish I were a part of it. The work you are doing is vital to the survival of our native pollinators. Thank you.

Thank you for this interesting discussion. I look forward to your findings.

What an insightful overview of this important pollinator research. Excited to see the finding and hear more about the multiyear experiment being planned.