Engaged learning design helps students comprehend the learning materials and apply the newly learned knowledge and skills to new contexts. Jessie Moore proposed six key principles for engaged learning, namely:

* “Acknowledging and building on students’ prior knowledge and experiences;

* Facilitating relationships, including substantive interactions with faculty/staff mentors and peers, and development of diverse networks;

* Offering feedback on both students’ work-in-progress and final products;

* Framing connections to broader contexts, including practice in real-world applications of students’ developing knowledge and skills;

* Fostering reflection on learning and self; and

* Promoting integration and transfer of knowledge” (Moore 2021; Moore, 2023).

This blog will showcase three course design projects using engaged learning principles to overcome design challenges, including challenging content, lack of student motivation, and/or difficulty transferring knowledge.

Design Case #1

Engaged learning Principle: Acknowledging and building on students’ prior knowledge and experiences

Design Challenge: Students are non-accounting majors and need more motivation to study accounting.

Design Solution: College students have all bought textbooks and paid bills for college education, even though they may not have any accounting training before. Building on students’ prior knowledge of bill paying and textbook purchases, the instructor created a mock-up student-run company and assigned students to work with accounting related to students’ activities, such as buying and selling textbooks and offering tutoring services, in order to make learning materials of “BA 315 Accounting for Decision Making” relevant and meaningful to students. The instructor also collaborated with Ecampus media team to create an online monopoly simulation game modified with Oregon State University themes to further engage students in accounting practices.

Design Case #2

Engaged Learning principle: Facilitating relationships, including substantive interactions with faculty/staff members and peers and developing diverse networks.

Engaged Learning principle: Offering feedback on students’ work-in-progress and final products.

Engaged learning principle: Fostering reflection on learning and self.

Engaged learning principle: promoting integration and transfer of knowledge.

Design Challenge: trauma-informed helping skills are challenging to teach in HDFS 462 online.

Design Solution:

Building on students’ prior knowledge and experiences (Discussion board activities)

The course developer used case study and group case discussion on developing a plan to help a client; Students individually practice attending and listening with single-word responses. Instructor provides feedback on both group work and individual work.

Also, instructor Modeling the empowerment process with recorded videos, students practicing helping skills, and the instructor offering feedback on students’ helping skills practices with peer partners in the classmates.

Connections to Broader contexts and promoting integration and transfer of knowledge: students practice helping skills with non-classmate clients; and instructor provides feedback.

Design Case #3

Engaged Learning Principle: Framing connections to broader contexts, including practice in real-world applications of students’ developing knowledge and skills.

Design Challenge: There is a lack of full access to construction sites especially for students in CE 427 Online Course to get hands-on experience and understand construction site structure fundamentals.

Design Solution: the instructor and instructional designer collaborated with the media team to design an interactive simulation called Clickable Structure to help students understand the most difficult concepts in the course: elements of structures and how various pieces relate to each other. The Clickable Structure simulation enables students to see each group of structures layer by layer according to their functions and the corresponding equations needed for calculations of weight bearing, etc.

As a Reflection Tool

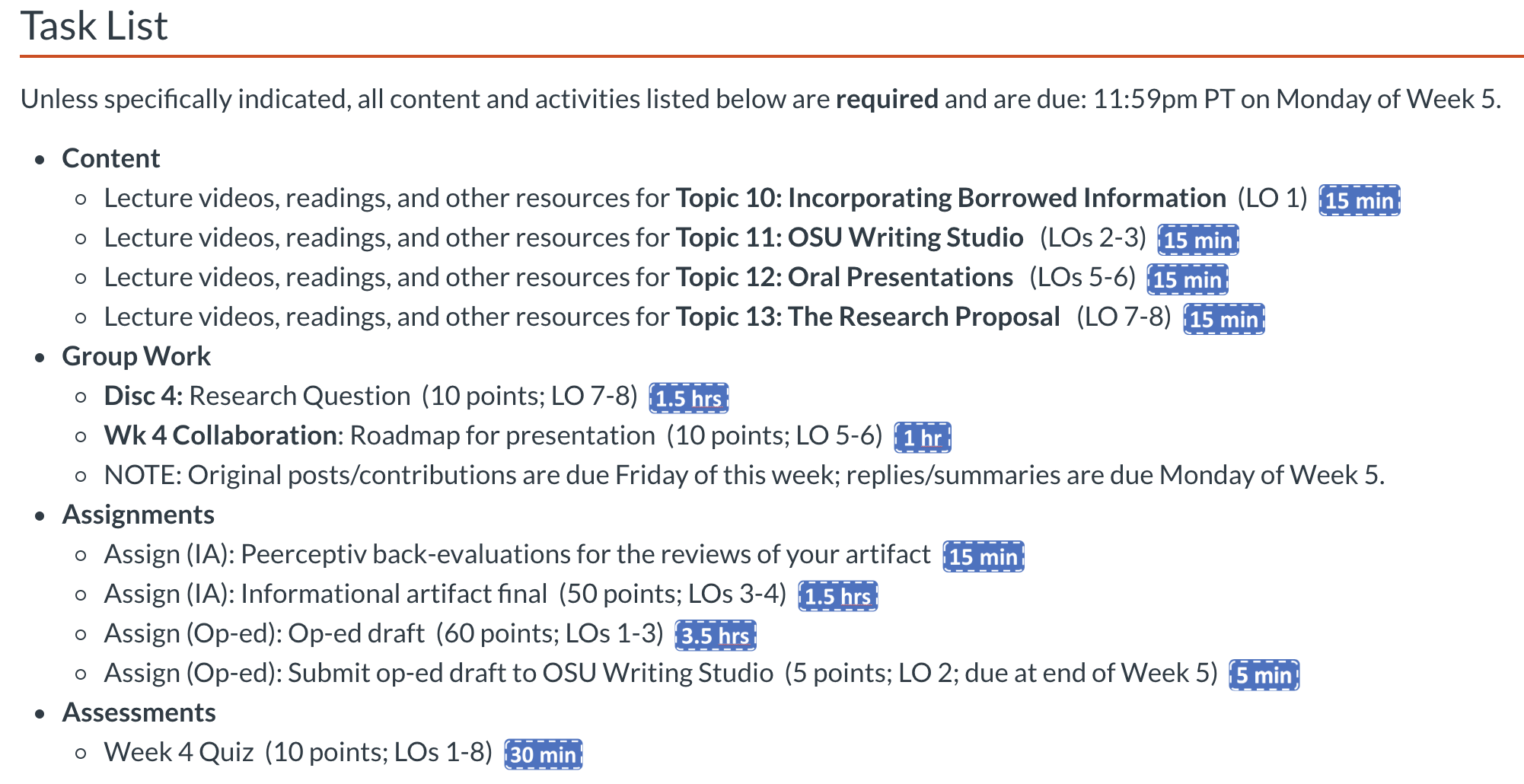

Another way to use the six principles of engaged learning is to change the statements in the principles to a list of questions for students to reflect:

1. What prior knowledge do I bring to this topic?

2. What new knowledge and skills I learned about this topic? How are these new concepts and skills and principles and relationships related to each other? How does individual pieces of information connect to make sense?

3. What feedback did I receive from instructor and classmates that gives me insights to this topic?

4. How is this topic related to broader contexts of main learning outcomes of this course or real-world applications?

5. How could I use what I learned about this topic into real-world application?

6. What new understandings did I gain from this reflection activity?

If you find these six principles of engaged learning meaningful and have adopted or adapted them in your teaching and learning, I encourage you to share with us (email tianhong.shi@oreognstate.edu) so we can build a collection of engaged learning cases and examples.

References

Moore, Jessie L. Key Practices for Fostering Engaged Learning: A Guide for Faculty and Staff. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, 2023.

Moore, Jessie L. 2021. “Key Practices for Fostering Engaged Learning.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 53(6): 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2021.1987787

(image from pxfuel.com)

(image from pxfuel.com)