by Jessica Alfaqih, WIC GTA

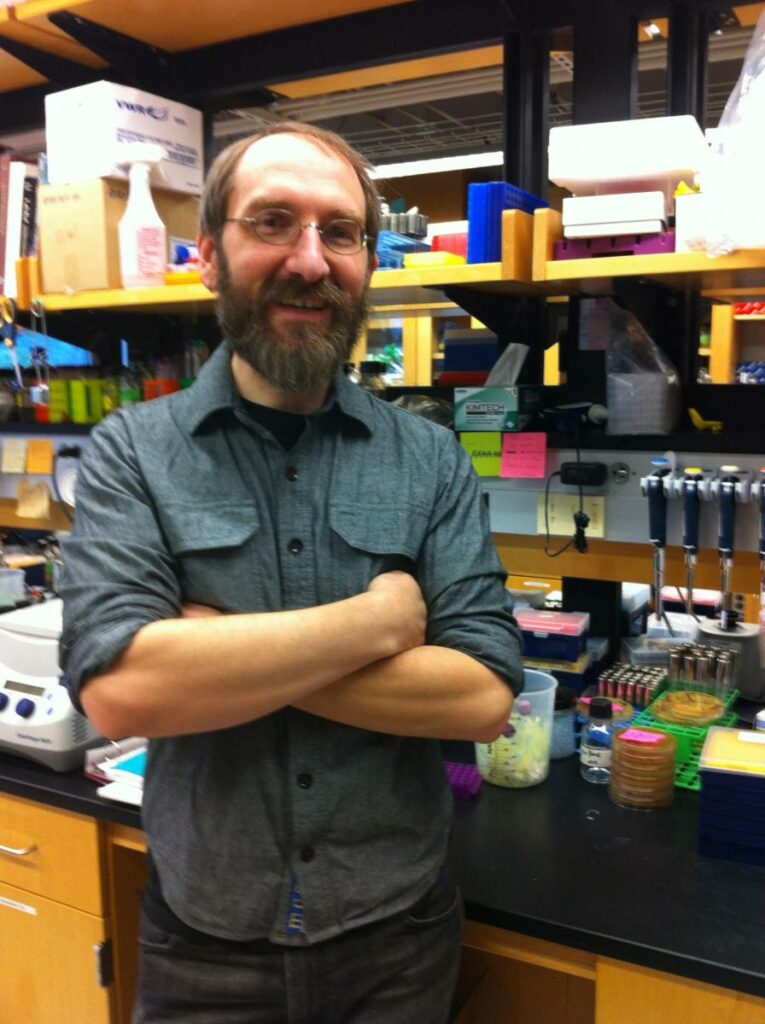

Dr. Shawn Massoni is an instructor in the Microbiology and BioHealth Sciences departments at Oregon State University. Dr. Massoni was also a 2020-2021 Inclusive Excellence Fellow where he investigated the history of traditional grading models, and adopted new methods for grading more equitably in his courses at OSU. As a WIC instructor, Dr. Massoni focuses on bringing real science into the classroom through Journal Clubs–a model in which students take turns presenting research articles to the class–as a way to actively engage students in practical skills for STEM. In this excerpted interview with WIC GTA Jessica Alfaqih, Dr. Massoni discusses his experience as an undergraduate with journal clubs, and how they afford unique practices for students wanting strong, relevant STEM skills.

Jessica Alfaqih: Can you start off by telling us what a journal club is?

Shawn Massoni: Basically, there is a presenter for the week who picks a primary research article that they will present to the group. They read an article, digest it, and communicate their findings in a concise and knowledgeable way to their audience.

JA: How did you get started with journal clubs?

SM: In the microbiology lab in which I was working as an undergrad, all students–graduate students, post-docs, and even undergrads–had to participate in journal clubs. It’s great preparation for teaching because, essentially, you have to teach the class. In my case, the “class” were rooms full of established researchers! It was the school of hard knocks.

Being in the lab was hard because you weren’t in a safe space, necessarily.

We had a big screen on the wall and the other side would pop up in the conference room, full of professors.

There weren’t any students on the other side; this was just the way lab professors got together and had intellectual jam sessions over papers that were of specific interest to our particular work.

As a student in the lab, you were expected to present with the other professors, and you would get a credit for it.

In that scenario, there were medical school professors and other heavy hitters there waiting for you to present a document that they completely understand and will punch holes in it–and you–without compunction.

That was tricky, but that’s really what got me into it.

JA: How does the way you teach journal clubs now compare to your experience as an undergrad?

SM: When I started out you had to sink or swim.

I don’t want to do that to my students, but I do want to expose them to the literature. If you’re getting into this field in any way, shape, or form–from graduate school to working in a clinic or going on to medical school–it’s essential that you see what real-world science is all about.

Every student presents on one paper and that’s the way the class runs.

I give a mini lecture. They have writing prompts, occasionally, during a lecture in which they do their informal writing in a physical journal.

Sometimes those low stakes assignments are where students feel that they can be more engaged and committed because the stakes are lower.

Once they can informally wrap their heads around the science, they are more prepared for taking a deep dive into the material they have to present.

JA: How did you get started with Journal Clubs at OSU?

SM: I inherited BHS 323, Microbial Influences on Human Health, from a professor who is now at Lane.

Much of the writing had really gone out of it over the years and I worked to get the WIC component back in it.

Informal writing helps students get used to communicating to different audiences, so I brought that back in with journaling and would lecture very briefly so that we could have more of a two-way discussion on a particular topic. We would also have a particular reading to discuss for that day, so in a way my classes are also reading intensives, without textbooks.

For those of us in the science disciplines, courses are mostly taught out of textbooks, which are very generalized, full of inaccuracy, and rarely updated. Students don’t get exposed as much as they should to the primary literature, which is what science really looks like in the publication sense.

Instead, scientific literature became our textbook–real-world research.

My WIC class helps adapt students to reading the science article format. Reading a science article is not like reading a textbook; it’s not generalized. Students are challenged by it because they don’t already have a strong basis for understanding this material.

And so the journal club is what we do in class.

JA: They’re more difficult, but a journal isn’t as intimidating as a 300 page long, hard-bound textbook.

SM: Yes, these articles aren’t looking at the entire discipline. They’re looking at one little bit that I can relate to other things that we’ve talked about.

It is, in a sense, the culmination of an entire discipline applied to a single question. You need to understand everything that goes into it and start to know that that’s what you need. It’s challenging. It takes practice. And I think that’s good.

JA: I’m curious if there are notable benefits you’ve noticed the students coming away with?

SM: They learn how to access the primary lit (a skill in itself), how to read the literature, and how to be critical about it, which is a skill that they’ll need to have. They’re going to get papers from all sorts of different realms that they’re not experts in. I try to help them refine a method for themselves and figure out how best to approach difficult readings when they’re confronted with them.

That builds confidence too.

I wish I could offer this kind of exposure to freshmen, but there’s not that opportunity in that particular class. So I try to bring this element into all my classes now, in whatever way I can–bringing in the primary literature, exposing them to that, instead of textbooks.

JA: It sounds like there’s a feedback piece to all of this that helps with student development. Could you speak more about that?

SM: There’s a very heavy feedback element, and that’s what makes it so challenging because they often feel like they don’t have the chops to be able to judge whether a paper is good or bad in a lot of ways. But I tell them to bring in their opinion too, because the primary lit is full of veiled opinion as well.

They can say what they found to be beneficial, or not so beneficial. They can say, “What do I want to know more about?” And then they start to reflect on their own work as they make comments on others’ work. This process is internal and metacognitive.

I think it’s beneficial they do this as this is what they’ll have to do as part of their careers later on. That’s maybe a bit of an assumption, but I think it’s critical for them to have this exposure.

One of the things we do as faculty is peer-review our co-faculty. We sit in on classes and check boxes: do they use updated, relevant material? Do they project what they’re saying? Do they give real world examples?

This is exactly why it’s so important and why I like to bring the peer review aspect of journal clubs into my classroom. Because this is science in the real world.

JA: Are there difficulties with journal clubs one could be on the lookout for and try to prevent?

SM: One critical question is how to motivate the students to actually read the article.

Only one person has to present each week and all the other people review it and give the presenter their review. They’re required to give at least one comment, critique, and there are boxes for them to check off to rank a presentation strong or weak. But there’s no accountability for doing the reading or not.

I want people to be there because they want to be, but at the same time this class is not an elective. Everyone’s there because they have to be for their degree, which is tricky. I want them to want the knowledge and to want to be there, but I don’t always get what I want.

JA: How do you or how might you get them to do the reading, short of assigning a letter grade? Are you considering any changes to your class in the future to help students better understand the value of doing the reading, and to encourage them to actually do it?

SM: To incentivize students to actually do the reading when they’re not presenting, I just started using a daily rhetorical precis.

Even if they haven’t read or have only skimmed the article previously, this forces them to at least re-access it at that moment in class, right before the presentation. This way, they can start to gain an understanding about the paper being presented, form an opinion, or even start to imagine possible questions.

I find that knowing they will have to write a live precis gives them motivation to have read the material and tried to understand it previously. It’s really all about priming their thinking to be present for the paper and the peer presenting, and to be able to offer some valuable questions and criticism.

This was impromptu just this term, born out of my frustration at students not appearing to have done the reading (and having no extrinsic motivation to do so), and so was not graded in any way, but in the future I will likely fold it into the graded “informal” writing category.

JA: Do you have any advice for other faculty who might be interested in starting a journal club?

SM: For me, it’s a no brainer. Journal clubs expose students to the reality of your work, of your discipline. The students get to discover science in the real world, not in a boring textbook. The research articles actually show a relevant, up to date thing happening, and they show how and why and this is what they do as opposed to just accepting what is written in a text.

It’s great to use primary literature no matter what discipline you’re in. It keeps things vibrant, dynamic and challenging. And it gives students a more accurate picture of what people in a given field actually do.