David P. Turner / February 20, 2025

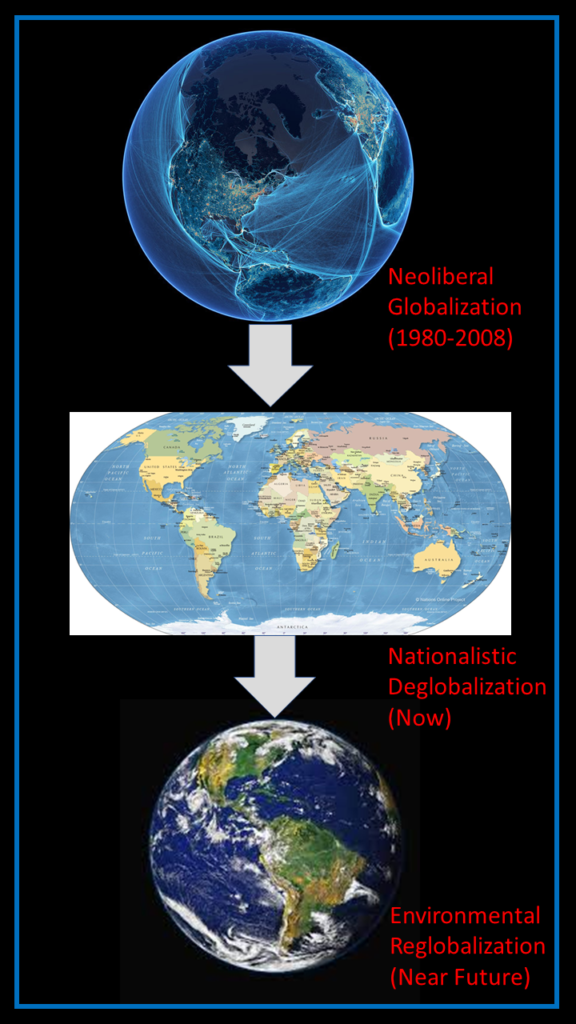

Figure 1. A stylized rendering of the integration of biosphere and technosphere. Image credit: Original Graphic.

Earth System Science studies the Earth system in terms of the whole, its parts, and the associated dynamics. The biosphere and the technosphere are well-recognized functional parts of the current Earth system, but while the biosphere helps maintain the global biogeochemical cycles and climate, the technosphere is disrupting them. The technobiosphere concept represents a potential fusion of these two parts into a matter-, energy-, and information-processing entity that advances planetary evolution.

Biosphere

In the early 20th Century, Russian geochemist Vladimir Vernadsky identified the biosphere as the sum of living organisms on the surface of Earth. He emphasized how the biosphere absorbs solar energy and uses the energy to construct and maintain order in the form of biomass. Earth system scientists have subsequently discovered that over geologic time, the biosphere has undergone major changes in the kinds of organisms it contains and in the way it contributes to maintaining the global biogeochemical cycles and global climate.

Technosphere

In a more recent conceptual advance, geologist Peter Haff identified the technosphere as the sum of all human-built technological artifacts on the surface of Earth, along with the human beings and institutions that manage those artifacts. Like the biosphere, the technosphere uses energy (mostly in the form of fossil fuels) to construct and maintain order. In this case, the order is in the form of machines and structures of various sorts networked together to support advanced technological civilization. The technosphere is expanding rapidly, and indeed we have entered the Anthropocene era in which technosphere metabolism has begun to act as a geological force.

The biosphere and technosphere concepts are helpful in thinking about Earth as a system, and how it changes over time. One notable observation is that the technosphere is now growing at an exponential pace and its growth is coming in part at the expense of the biosphere – specifically a loss of biodiversity and ecosystem diversity.

The technosphere – unlike the biosphere – largely does not recycle its wastes, e.g. vast amounts of plastic end up in landfills, and CO2 is freely dumped into the atmosphere from the combustion of fossil fuels. The current trajectory of technosphere impacts on Earth’s climate and biosphere is leading to an instability in the Earth system that will challenge humanity’s ability to adapt.

Technobiosphere

For the long-term welfare of humanity, the next step in planetary evolution may well be a fusion of the biosphere and technosphere. This new entity – the technobiosphere – deserves a label because, although it will retain a well-functioning biosphere and technosphere, much of its self-regulation will depend on human consciousness and, perhaps eventually, Artificial Intelligence (AI).

What that fusion will mean in practice is that the technobiosphere is run on renewable energy, largely recycles its waste materials, and does not grow at an exponential rate. It would have the capacity to monitor itself, maintain itself, and alter its impacts on the global biogeochemical cycles. New stabilizing negative feedback loops would link components of the technosphere, biosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and geosphere.

The global carbon cycle in particular is amenable to technobiosphere regulation by means of controlling energy-based emissions of carbon dioxide and methane, reducing carbon emissions from deforestation, and increasing biologically-based carbon sinks by tree planting and protection of undisturbed ecosystems.

Integration

Clearly the limited contemporary integration of biosphere and technosphere is insufficient to call the combination a technobiosphere.

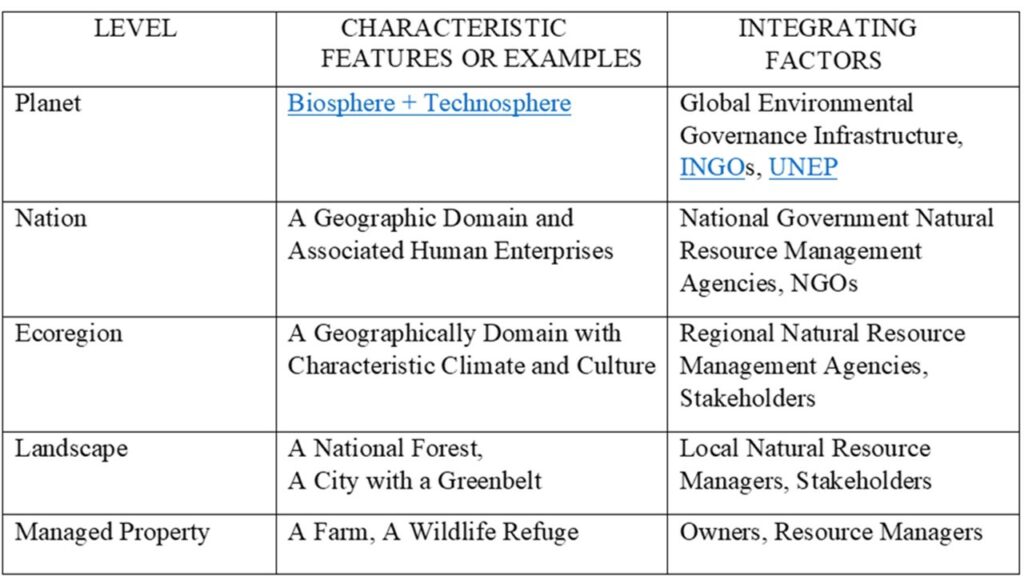

As to what will drive an enfolding of the technosphere back into the biosphere, I am afraid it is on us. Most importantly, a functional infrastructure for global environmental governance has to be developed to coordinate the global community. Key principles on which to base that governance include sustainability and habitability.

Sustainability refers to a relationship between the technobiosphere and the rest of the Earth system such that the global environment is stable enough to support successive generations of humans. If the global climate is warming by 3oC per 100 years because of carbon-based energy generation, the relationship is not sustainable.

Habitability refers to a planetary environment that supports all life forms. If the growth of techno-artifacts is causing a 50% loss in biodiversity per 100 years, the habitability of the Earth is in decline. In contrast, habitability could increase if continued urbanization, and an eventual decline in the human population from the global demographic transition, allowed for more of the land and the ocean to be dedicated to conservation purposes.

The development of AI represents both threats and opportunities in relation to technobiosphere evolution.

A key threat lies in how AI will speed up the technosphere (hence making greater demands on natural resources) and make the technosphere more autonomous. Super-intelligent AI bots and agents may eventually care more about their own survival than the survival of the biosphere.

AI-based opportunities lie in spurring scientific advances that reduce human impacts on the Earth system, and in helping educate natural resource managers and planetary citizens. AI-based inquiry (with large language models) is a new form of perception ̶ an intelligence capable of surveying information at the planetary scale and delivering a synthesis accessible to our individual minds.

Conclusion

The way language works, the existence and meaning of specific words is socially constructed (by way of cultural evolution). The biosphere concept allows us to see a planetary scale, energy-harvesting, and order-producing entity that helps regulate the global biogeochemical cycles and climate.

The technosphere concept allows us to see a new human-constructed, planetary scale, control force now altering Earth’s biosphere, biogeochemistry, and climate in a destabilizing manner.

We need to start imagining an integrated technobiosphere ̶ a part of the Earth system able to monitor and regulate itself so as to survive and thrive at a geologic time scale.