David P. Turner / February 1, 2021

Earth system scientists think of planet Earth as composed of multiple interacting spheres. The cryosphere is a term given to the totality of frozen water on Earth – including snow, ice, glaciers, polar ice caps, sea ice, and permafrost.

The cryosphere has a significant effect on the global climate because snow and ice largely reflect solar radiation, hence cooling the planet.

Unfortunately, the cryosphere is melting. That loss of snow and ice is providing a significant positive (amplifying) feedback to anthropogenically induced global warming.

Over the course of Earth’s geological history, the cryosphere has existed as everything from nearly 100% coverage of the planetary surface around 700 Mya (million years ago) i.e. snowball Earth (Figure 1) to virtually disappearing during the Hothouse Earth period (about 50 Mya).

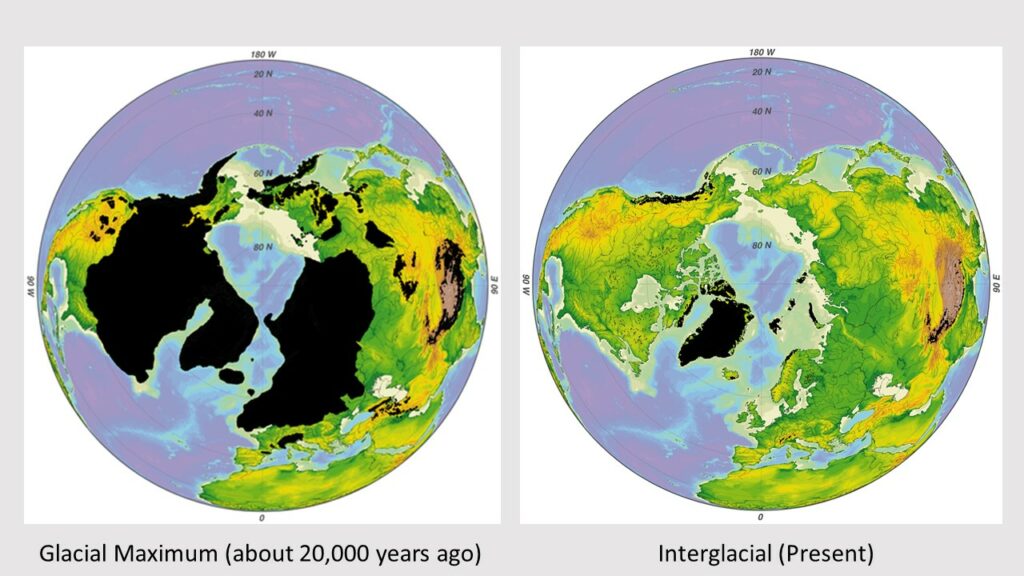

The multiple glacial-interglacial cycles over the last several million years were initiated by changes in sun/earth geometry (the Milankovitch cycles), but strengthened by changes in snow/ice reflectance along with changes in greenhouse gas concentrations.

The culprit in the current melting of the cryosphere is something new to the Earth system – the technosphere. This recently evolved sphere consists of the totality of the human enterprise on Earth, including its myriad physical objects and material flows.

By way of fossil fuel combustion, the technosphere is driving up the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and correspondingly, warming the global climate. That new heat is causing reduced snow cover, receding glaciers, melting of ice caps, and loss of sea ice. By various anthropogenically driven mechanisms, the cryosphere is also said to be “darkening” and hence melting quicker because more solar radiation is absorbed.

Projections by Earth system models of cryosphere condition over the next decades, centuries, and millennia suggest it will significantly wane if not disappear.

Besides the positive feedback to climate change by way of reflectance effects (and release of greenhouse gases from permafrost melting), the diminishment of the cryosphere will have profound impacts on the technosphere.

- The circulation of water through the hydrosphere on land is regulated in many cases by accumulation of snow and ice on mountains. That water is subsequently released throughout the year, thus providing stable stream flows for downstream irrigated agriculture and urban use.

- The melting of glaciers and the polar ice caps will drive up sea level. If all such ice is melted (over the course of hundreds to thousands of years), sea level is projected to rise 68 m. The magnitude of sea level rise projected over the next 100 years for intermediate emissions scenarios is on the order of one meter.

- It remains controversial, but reduction of snow and ice cover may alter the behavior of the jet stream and could induce more extreme weather events in mid- to high latitudes of the northern hemisphere.

Efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will certainly slow the erosion of the cryosphere and should be made. The precautionary principle suggests we avoid passing tipping points associated with melting of the Greenland ice cap and the Antarctic ice cap. However, the momentum of environmental change is strongly in that direction.

Once these ice caps are gone, there is a hysteresis effect such that the ice does not return with a simple reversion to the current climate (e.g. by an engineered drawdown of the CO2 concentration).

The planet is headed towards a warmer, largely ice free, condition. The biosphere has been there before. The technosphere has not. Humanity will be challenged to develop adequate adaptive strategies.

Recommended Video: What is the Cryosphere │How it Affects Climate Change