This entry in our “Plant of the Week” series is written by Georgia Vatcoskay, an undergraduate research assistant and Botany and Plant Pathology student at Oregon State University.

Purple coneflower, also known as Echinacea purpurea (Asteraceae), is a popular perennial herb that sprouts showy blooms from late spring to late summer. This plant is native to prairies in the central and eastern United States (1) but can be found in many Pacific Northwest gardens and nurseries. Though it’s non-native, purple coneflower doesn’t outcompete native plants and is rather low-maintenance. It develops woody rhizomatous roots each year to produce more blooms, with the largest stems reaching 3 feet tall (1).

It’s attractive to pollinators like bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds (1). A variety of bee species are common visitors, such as the western honey bee (Apis mellifera), bumblebees (Bombus spp.), and solitary bees (Halictus spp., Agapostemon spp.) (2). Interestingly, during Taylor’s summer field research of 2025, we found 50% of gardeners had purple coneflower in their pollinator garden. You can read more about Taylor’s research in their recent blog post “Science Behind the Scenes: Pacific Northwest Pollinator Gardens.”

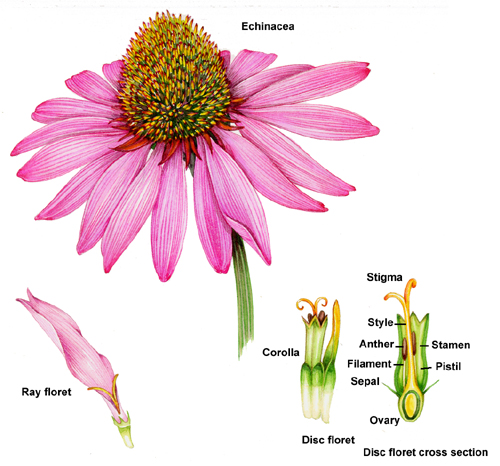

If you’ve ever observed a purple coneflower on a summer day, you may have seen bumblebees collecting pollen from the orange disc florets, contained in the cone-shaped flower head. As a relative of sunflowers and other daisy flowers, the flower head contains many smaller flowers, termed disc florets. These spike-like flowers gave this plant the scientific name “Echinacea”, deriving from the Greek word echinos, meaning spiny or prickly.

The pollen and nectar of these flowers boast impressive nutritional profiles. The nectar is especially sweet, producing similar sugar concentrations to high-sugar flowers like lavender (3, 4). The pollen has a balanced mix of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, and serves as a high-protein snack for native Bombus species (5).

Purple coneflower has a history of medicinal and ethnobotanical value. Indigenous people of the Great Plains used the roots and leaves medicinally for pain relief (1). This knowledge carried over to early European-American settlers and is still a popular herbal remedy to this day. Research has since confirmed its immune boosting and anti-inflammatory properties (6), and you can find purple coneflower in many health and wellness products such as teas and supplements. If you’ve ever reached for immune support tea, there is likely Echinacea in it!

Being an important food source for many pollinators and popular in ornamental landscaping, purple coneflower is ubiquitous in gardens across North America. Despite being non-native to the Pacific Northwest, its many benefits prove it can be a great component in gardens. They do well in most soil types and require little fertilization (1), growing beautiful flowers each year with minimal effort.

References

- Stevens, M. (2006). Plant Guide: Eastern Purple Coneflower. USDA NRCS National Plant Data Center. https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/cs_ecpu.pdf

- Melittoflora. (2025). Oregon Bee Atlas. https://oregon-bee-project.github.io/melittoflora/viz.html

- Wist, T. J., & Davis, A. R. (2005). Floral Nectar Production and Nectary Anatomy and Ultrastructure of Echinacea purpurea (Asteraceae). Annals of Botany, 97(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcj027

- Carisio, L., Schurr, L., Masotti, V., Porporato, M., Nève, G., Affre, L., Gachet, S., & Benoît Geslin. (2022). Estimates of nectar productivity through a simulation approach differ from the nectar produced in 24 h. Functional Ecology, 36(12), 3234–3247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14210

- Vaudo, A. D., Patch, H. M., Mortensen, D. A., Tooker, J. F., & Grozinger, C. M. (2016). Macronutrient ratios in pollen shape bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) foraging strategies and floral preferences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(28), E4035–E4042. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606101113

- Borchers, A. T., Keen, C. L., Stern, J. S., & Gershwin, M. E. (2000). Inflammation and Native American medicine: the role of botanicals. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(2), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/72.2.339