National Moth Week was last week (July 19-27, 2025), which reminded me of an article I had written about Artificial Light at Night (ALaN). This article was originally written for the Hardy Plant Society of Oregon Quarterly Magazine (HPSO Quarterly) and was greatly improved by the review and feedback of the HSPO Quarterly editorial team.

The environmental impacts of artificial light at night are both positive and negative. Human-created nighttime lighting plays an essential role in modern society, extending nighttime work and socialization hours and providing a sense of increased safety and security.[i] However, artificial light at night (ALaN) can also negatively affect the circadian rhythms of plants, birds, insects, humans, and other animals and organisms, resulting in significant ecological harm.

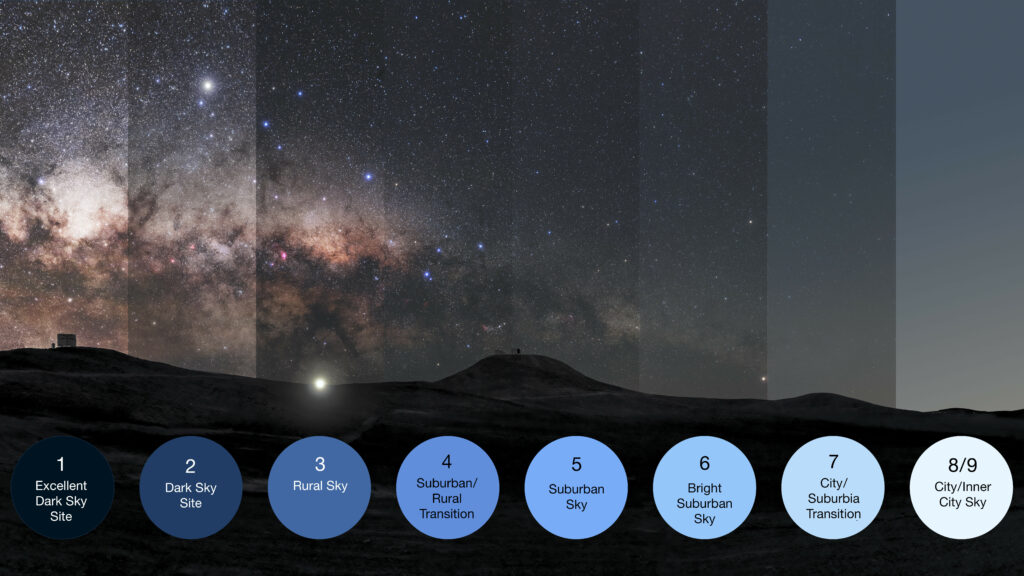

Light emissions into the atmosphere have increased by approximately 49 percent between 1992 and 2017, according to measurements made via satellite.[ii] No doubt, this value greatly underestimates nighttime light emissions, since satellites are unable to detect visible wavelengths in the blue spectrum, which are emitted by Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs). LED lights are quickly becoming the dominant form of outdoor garden lighting available on the commercial marketplace, due to their small size, lower energy use, and ability to shine concentrated light and vivid colors. When including the blue component of artificial light at night (ALaN), scientists suggest that nighttime light emissions have increased by as much as 270 percent.[iii] ALaN is further propagated, as it reflects off of surfaces and atmospheric dust or water vapor, creating increased night sky brightness known as skyglow.

ALaN Disrupts Circadian Rhythms

Circadian rhythms are the 24-hour patterns that an array of physiological processes follow, including photosynthesis, brain activity, hormone production, and cell regeneration. Exposure to natural light is crucial for keeping a healthy circadian rhythm. ALaN, particularly the blue wavelengths found in LEDs, can disrupt or impede circadian rhythm. A recent Oregon State University study demonstrated that exposure to the blue light found in LEDs, cell phones, and tablets reduced the lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster fruit flies by as much as 50 percent.[iv] Fruit flies are a common model organism in biology, since they are easy to work with in the lab and share many cellular and developmental mechanisms with other animals, including humans. The researchers found that exposure to 12 hours of blue light per day damaged retinal cells, promoted brain neural degeneration, and accelerated aging, ultimately resulting in the premature death of fruit flies.

In terms of animals that we may encounter in the garden, ALaN promotes earlier singing at dawn in songbirds (Ritz-Radlinská et al. 2025),[v] increases squirrel mortality by seven times possibly due to increased foraging time for day-active squirrels (Henke et al. 2022),[vi] and even disrupts sleep cycles in honey bees (Kim et al. 2024).[vii] For humans, the blue wavelengths in LED AlaN can suppress melatonin production, disrupt sleep, and increase risk of cardiovascular disease, to the extent that a majority of surveyed scientists support adding warning labels on blue-enriched LED lights, indicating that they “may be harmful if used at night”.[viii]

ALaN Disrupts Migration and Navigation

ALaN can form an ecological trap for some bird species, which are attracted to light and become disoriented. This disorientation can result in fatal collisions with solid structures. Even when collisions are avoided, migratory birds may end up turning in circles around buildings that emanate light, negatively impacting their migration time, energy stores, and long-term survival .[ix] ALaN and associated skyglow also affects where birds choose to stopover to rest, refuel, and seek shelter from adverse weather. More birds stopover in areas with higher skyglow, which may result in these illuminated areas serving as ecological traps: highly attractive sites that ultimately harm an organism’s survival or reproduction. To avoid the negative impact of ALaN on birds, bird conservation societies encourage building owners to turn off lights and close blinds between 11:00 pm and 6:00 am, particularly during key migration periods.

Nocturnal insects are also attracted to artificial light at night, often to their detriment. Moth growth and reproduction is reduced in areas with high ALaN, likely because of disrupted navigation and increased energy expenditure from prolonged flight. ALaN also obscures moths’ abilities to perceive the flower colors of preferred host plants, which negatively affects their nutrient intake.[x] Moths and other insects attracted to lights are also more likely to be eaten by bats, spiders, and other predators who use ALaN as a “fishing net” of sorts, to consolidate and capture prey.

ALaN Obscures Communication and Alters Plant Phenology

ALaN obscures the light signals of fireflies, click beetles, cave glow-worms and other organisms that use bioluminescence to find mates and deter predators. Studies of plants growing close to streetlights have shown that ALaN can also induce earlier flowering, prolong leaf retention, and promote invasive plant establishment.

Responsible Outdoor Lighting Principles

DarkSky is an international organization that works to reduce ALaN and promote responsible outdoor lighting. They offer five principles for consideration.

First, use light only if needed, and where it will be useful. It is useful to have a walkway and front door illuminated at night, particularly when returning home at night. On the other hand, illuminating an ornamental water feature at night is likely not necessary.

Second, light should be targeted and directed, so that it only falls where it is needed. You can use shielding and proper placement of lights to prevent the escape of light into the night sky and ensure that it falls where it is needed.

Third, lights should be no brighter than necessary. Use the lowest level of light that is needed, and be mindful of how surfaces might reflect light upwards.

Fourth, use light only when needed. Timers, dimmers, and motion detectors can be used to ensure that light is turned off or dimmed, when possible.

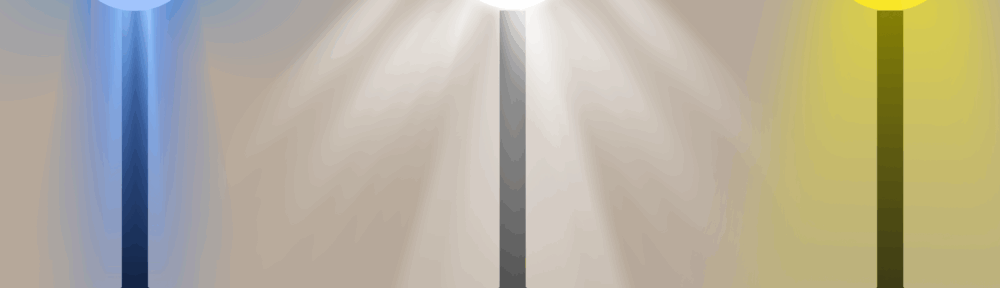

Finally, use warmer-colored lights, when possible. Warmer colored lights have an added benefit of attracting fewer insects. Avoid shorter wavelength lights, in the blue-violet range, whenever possible.

ALaN has a myriad of benefits, including the perception of increased safety and security at night and the facilitation of nighttime work and socialization. However, ALaN can also negatively affect organisms’ circadian rhythms, nighttime navigation, signaling and communication, among other impacts. By adopting relatively simple changes in our outdoor lighting schemes, we can do a better job of balancing the benefits against the costs of ALaN.

[i] Peña-García et al. 2015. Impact of public lighting on pedestrians’ perception of safety and well-being. Saf. Sci. 78:142–48

[ii] Falchi et al. 2016. The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Sci. Adv. 2:e1600377.

[iii] Sánchez de Miguel et al. 2021. First estimation of global trends in nocturnal power emissions reveals acceleration of light pollution. Remote Sens. 13:3311,

[iv] Nash et al. 2019. Daily blue-light exposure shortens lifespan and causes brain neurodegeneration in Drosophila. NPJ aging and mechanisms of disease 5(1), 8,

[v] Ritz-Radlinská et al. 2025. Synergistic effect of light and noise pollution on dawn and dusk singing behavior of urban European blackbird: Changes during nesting season. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 282, 106486,

[vi] Henke et al. 2022. Holiday lights create light pollution and become ecological trap for eastern fox squirrels: case study on a university campus. Human–Wildlife Interactions, 16(1), 12.

[vii] Kim et al. 2024. Exposure to constant artificial light alters honey bee sleep rhythms and disrupts sleep. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 25865.

[viii] Moore-Ede et al. 2023. Lights should support circadian rhythms: evidence-based scientific consensus. Frontiers in Photonics, 4, 1272934.

[ix] Falcón et al. 2020. Exposure to artificial light at night and the consequences for flora, fauna, and ecosystems. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 602796.

[x] Briolat et al. 2021. Artificial nighttime lighting impacts visual ecology links between flowers, pollinators and predators. Nature communications, 12(1), 4163.

1 Comment

Add Yours →Useful article 👍