Today is the 50th anniversary of earth day. I am almost as old as earth day (I will turn 50, next February), and am finding myself in a reflective mood.

Ever since I was a child, I have been fascinated by and loved nature. I used to try and catch lightning bugs, and put them in a mason jar, hoping to catch so many that I could make a lantern. Today, when I visit my folks near my childhood home, nary a lightning bug can be found. Scientists suspect that increased landscape development has removed the open field habitats and forests that the lightning bugs depend upon to display their mating signals and to live. Light pollution likely also plays a role.

My time in college was my first real exposure to nature. I worked at Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, supporting the work of James Wagner when he was a graduate student at UMBC. He was studying wolf spiders, and I fell in love with these amazing creatures. Did you know that wolf spider mommas carry their young on their back ~ at least for the first few days of a baby spider’s life? Did you know that to collect wolf spiders, you go out at night with a flashlight . . . shining the flashlight into the forest floor litter, to find eight tiny glowing eyes staring back at you? Wolf spider eyes glow, as an adaptation to capture more light (enabling them to see better) when hunting at night. Like a cat’s eye, wolf spiders have a tapetum at the back of their eye . . . a mirror that re-reflects light back out, and lets the spider’s eyes have a second shot at capturing that light. My time working with James was magical. For the first time in my life, I gained the skills to identify trees, and wildflowers, and birds, and insects. I tell people that it was as if a scrim had been lifted from my eyes, and I saw the world in an entirely different light. I was forever changed, by this newfound knowledge that allowed me to ‘read’ the natural world in a different way.

As a graduate student, I studied salt marsh insects on the New Jersey coastline. I had never been to a salt marsh before, despite living within an hour of the ribbon of salt marsh that hugs the eastern seaboard. I saw horseshoe crabs for the very first time. I saw the fishing spiders in the genus Dolomedes that I had read about in books. I went bird watching and butterfly hunting with scientists who were generous with their time and knowledge, most notably, my advisor, Robert Denno. Now, so much of that ribbon of coastline has been destroyed. What remains is at risk due to increased nutrient pollution from fertlizers and run-off.

My post-doctoral work was spent in California on many projects, including studying the food webs of cotton fields that were using organic or conventional production practices. From talking to the farmers and stakeholders, I learned that there are not insurmountable impediments to growing organic cotton. The problem was that there was a limited market for organic cotton, grown in the United States. Growers who would plant organic cotton faced an uncertain market and reduced yields. Often, reduced yields might be compensated for with a premium price for organic products. But not in the case of US-grown organic cotton. This is when I first started to realize that science can not work in a silo, but that an understanding of economics and the social sciences is critical to promoting more sustainable solutions.

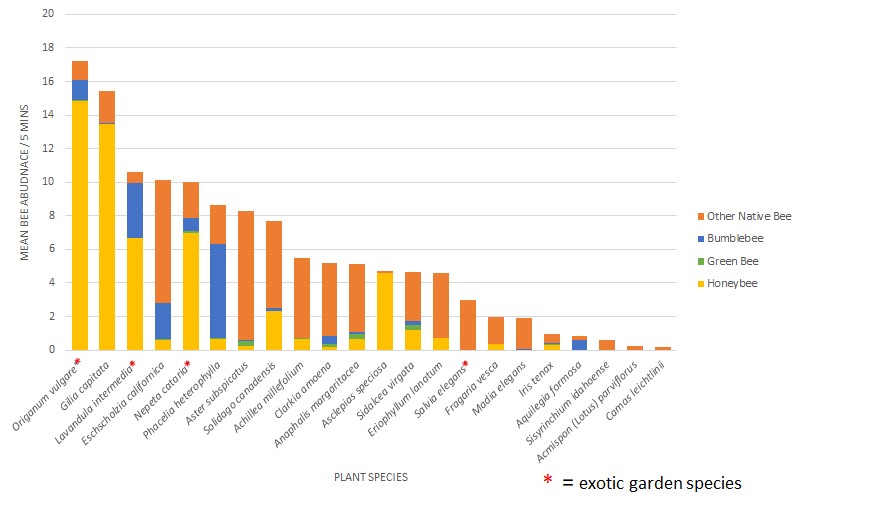

My first faculty position was at Fordham University in the Bronx. I had no idea what I would study, as an entomologist in the Bronx. Luckily, I had the great fortune of taking on Kevin Matteson as my first graduate student. Kevin had been studying the birds of New York City community gardens. I asked him if he might be willing to instead study insects. His work was ground-breaking and is heavily cited, showing the potential of small garden fragments in one of the most heavily populated cities in the world, to support a diverse and abundant assemblage of insects. He also showed that the strongest predictor of butterfly and bee diversity in gardens was floral cover. Through Kevin’s work, as well as associated work by Evelyn Fetridge, Peter Werrell, and others in our Fordham lab group, I became convinced that the decisions that we make in home and community gardens have the potential to make a real and positive difference in this world.

I came to OSU in 2007, for the opportunity to work with about 30 faculty and staff and between 3,000-4,000 volunteers who were dedicated to sustainable gardening. Coming from a teaching and research position to an Extension position was initially a challenge for me. I recognized importance of bringing good science to Extension and outreach work, but I didn’t know exactly how I would or could contribute. In 2016, I started the Garden Ecology Lab at OSU, mostly because I was more convinced than ever, that having good science to guide garden design and management decisions can truly make a positive difference in this world. I sometimes talk about ‘how gardening will save the world’, which is a lofty and aspirational goal. But, I truly believe (and science backs up this belief), that the decisions that we make on the small parcels of land that we might have access to in a community or home garden matter. These design and management decisions can either improve our environment (by provisioning habitat for pollinators and other wildlife) or harm our environment (by contributing to nutrient runoff in our waterways, or by wasting water when irrigation systems fall on the sidewalk more than on our plants).

This is one reason that I stand in awe of the Master Gardener Program. When I was purely a researcher, rarely interacting with the public, I doubt that many people were able to take our research findings and apply them in their own yard. When I was initially struggling with my new Extension position, I went to my former Department Head at the University of Maryland entomology deparment, Mike Raupp. Mike had a lot of experience with Extension and outreach, in addition to being a world-reknown researcher and a super-nice person. I remember him saying ‘Gail, when you publish a research paper, you’re lucky if 20 eggheads will read it. When you talk to the Master Gardeners, you have the opportunity to make real change in this world.’

And together with the Master Gardeners, I hope that is what we have done. I hope that is what we will continue to do. I hope that we find new and novel ways to discover how folks can manage pests without pesticides, to reduce water use in the home garden, and to build pollinator- and bird-friendly habitat. And then I hope that we will reach and teach our neigbhors and friends how to appreciate the biodiversity in their own back yard, and the small changes that they can make to improve the garden environment that they tend. I hope that we can instill a wonder for the natural world in the next generations, and to preserve or improve the natural world, so that our kids, and grandkids, and subsequent generations can hunt for lightning bugs, or spiders, or butterflies.

And I want to do it with you, dear gardeners. Together, we truly can make a difference.

2 Comments

Add Yours →You and your article brought tears to my eyes.

Thanks for this fascinating look at how you got to where you are. Your path may have been convoluted, but we are lucky you ended up running the MG program in Oregon.