By Alexander Mahmou-Werndli and Erin Vieira

Ana Milena Ribero is an Assistant Professor in the School of Writing, Literature, and Film. Her research and teaching mainly focus on rhetorics of im/migration, rhetorics of race, critical literacies, Latinx rhetorics, and Women of Color feminisms. In addition to courses exploring these topics, she has taught a collection of OSU’s Writing II courses including Argumentation, Writing for the Web, and Technical Writing. For this interview, WIC GTA Alex Werndli and intern Erin Vieira sat down with Dr. Milena Ribero to ask about literacies, her pedagogy, and tips for responding to language variety in the writing classroom.

Teaching with writing has an audience which includes faculty from across the disciplines. To start off, how would you explain literacies to someone with no background in writing studies?

First of all, we use the plural to connote that there are multiple literacies, not just one literacy. Traditionally, people think that there’s literacy: you’re either literate or illiterate. But when you broaden your definition of the term, you start seeing that there are multiple. I think my definition of the term is that literacy is the ability to use language to create a better world. When I think about literacy and especially literacies as using language or using communication to actually work towards a better world, that gets very blurry with rhetoric for me; I look at rhetoric as not just using language, but using symbolic communication as a whole to create meaning. And so, I think that literacy is very closely related to rhetoric, especially when we remove it from its traditional definition based on alphanumeric literacies.

I also kind of struggle with the word ‘language’ because when we think about language, we think of the written word or even just speaking certain languages of power, and I think that’s a little bit limiting. There’s a lot of work being done on literacies that have nothing to do with language, that have to do with the land and protest (not that a protest doesn’t have anything to do with language).

I’ll give you a couple of examples of what I mean. One of the articles that I read with my class recently talks about land-based literacies stemming from indigenous ways of knowing as a way to learn and know and relate to the land in ways that inform actions which advocate for and seek to create a better world. Another one I’ve read: there’s a scholar by the name of Steven Alvarez who writes about taco literacies – like the food. And the way that he writes about taco literacies, you could almost ‘read’ a taco and connect to all these cultural practices, right, of the food, the different ingredients, of different spices, the different meats that they put in there, corn or flour tortillas; then connect to labor practices, like the labor, the agriculture, or labor of planting corn, picking the corn and the tomatoes, all the social aspects of those labor practices and unfair conditions. So, you can learn a lot from knowing how to read a particular dish.

And so, I wonder how that connects to my definition of using language to create a better world. Maybe not just ‘using language’ but ‘reading.’ Like, maybe it incorporates reading practices as well as writing and speaking and creating practices. Because in that case with taco literacies, you’re really learning how to read a food to understand the ways that we’re all connected. Even if we just follow the trajectory of one ingredient, we can see all the people that are involved in making that ingredient, creating it, and being able to put it on your plate.

I’m teaching an intro to literacy studies class right now, we were thinking about what food would not be this socio-cultural window to dig deeper into, and we really couldn’t think of anything that would be devoid of a cultural factor. Even something like a hot dog- there’s so many aspects that you could look into about that dish as a cultural practice and labor practices and all these other things.

Yeah, if you think about it, even fast food like that still has its roots.

Right, and so I like to think about literacies as a way of reading something. I like the idea of fast food too, because when I think about food, I think about labor and about how we are so disconnected from the labor and the people that worked to bring this food to us. And fast food – I think we barely ever think about the labor behind it. If we think of McDonald’s, we think of a traditionally American food world. But, a lot of times, migrant workers are actually the ones creating that food and making sure that it comes to our plates. A lot of times, they are people that don’t even live in this country, so it’s like you’re creating this American idea through the hands and sweat and blood and tears of the other.

You’ve spoken about multiple literacies, both non-linguistic and linguistic. What would you say welcoming non-privileged varieties of English in the writing class looks like?

I think that it could look a few different ways, but I think probably the most important thing that instructors and professors throughout the disciplines can do is to help their students realize that there’s not just one variety of English but that there are Englishes. Standard English is just one variety (that is, the privileged variety) but that doesn’t make it hold more truth or expressive ability or anything else than any others. So, even if you’re not comfortable as an educator welcoming different varieties of English into your classroom, I think that if you approach standard English as what it is – a variety of English that is, I think, always connected to white middle-class ways of knowing and being and speaking and making meaning – then you’re doing pretty good. Because then at least students know that Standard English is like an artifact. It’s like a technology that they must learn so that they can enter certain businesses or certain discourse communities, but it’s not the only way or the most valuable way or the best way to express yourself.

“Probably the most important thing that instructors and professors throughout the disciplines can do is to help their students realize that there’s not just one variety of English but that there are Englishes.”

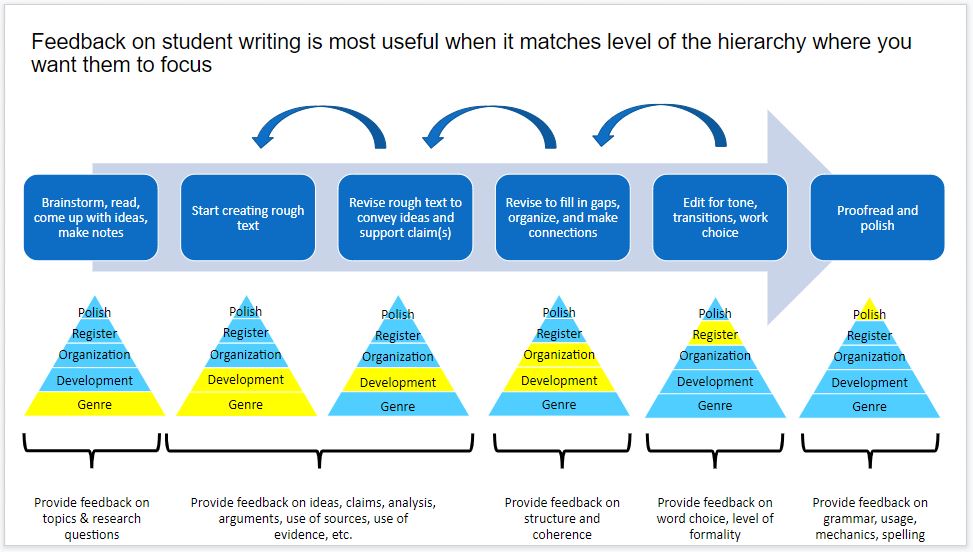

But if you are more comfortable incorporating other varieties of English into your classroom, I think you could do so a lot of different ways. A lot of instructors are most comfortable allowing students to plan, to take notes, or to do the invention part of the writing process in their own language varieties. Instructors with international students, for example, might say it’s okay if you want to take notes in your home language or your first language or in a mixture of English and your first language. Often, students don’t take you up on that. I’ve been in classrooms where I said you could write whichever way you want in your outline, and many students still want to do it in standard English, just because we’re so trained that that’s the only way. But even opening up that door… I think notes are a way that a lot of people are comfortable with, because again, it’s not something that you have to grade (or maybe you do, but it’s just a pass-fail kind of thing).

And would you say that opening the door has the potential to change students’ learning experiences?

I think it could help people be more comfortable because there’s a lot of fear in writing in a standard English that is further away from the ways that you speak at home. So, if you speak another language at home, or if you’re speaking African American Vernacular English, and you have to write in standard English, it can be scary because it’s this whole performance of competency and belonging… like if you can’t write standard English, you don’t belong in the university. That’s kind of the subtext, the message, that we often send to students, even though that’s obviously not intentional. Maybe opening the door will make students feel like their ways of knowing and communicating are valued. And I think that can go a really long way in engaging students more in their education, especially minoritized and underrepresented students. That’s what we want to do as educators, I think in any field: make sure that those who are underrepresented and marginalized actually feel like “this is your institution too, this is your university, this is your classroom. Just because there’s not that many of you in here doesn’t mean that it’s not yours.” And hopefully, if we make it a friendlier, more open space for minoritized and underrepresented students, then we will actually be able to recruit and retain more minoritized students.

At later stages in the writing process then invention, what are some best practices for teachers who are responding to writing which shows markings of being written in a dialect other than their own?

I think that I can give you multiple approaches. So, my approach (and I think it’s maybe controversial) is to just not really focus on correctness but focus instead on ideas and rhetorical effectiveness. I want students’ writing to be purposeful. Ideally, if students are using a language variety that is not their own, it should be for a purpose. But I understand that that’s not always the case, that sometimes students are not fully knowledgeable on how to express an idea in standard English, and so they use a language for it that is not standard English and not accepted in the institution. I try not to ever correct that because it doesn’t bother me as long as I understand what they’re writing, that an attempt was made to fit the genre that I’m trying to teach, and that the ideas are there. Correctness really is not the most important thing.

But I think that that’s controversial. I think that a lot of people feel like flawless writing or as close to it as possible is the goal. First of all, I don’t think there is flawless writing. I don’t think I’m a flawless writer. Flawless writing is a standard that we’re definitely not going to reach with our students when we have them for 10 weeks. But I think if someone was really intent on having their students’ writing fit into standard English, then maybe I would approach it as almost a translation instead of an error. When we think of different varieties of English as errors, we are devaluing students’ cultures, right? Let’s say somebody comes from rural Appalachia, and they’re expressing themselves in a way where maybe they use the word “ain’t” or a double negative or they didn’t put the apostrophe in the possessive. That’s what I’m talking about – like, I still know what you mean. Even if you didn’t add the apostrophe, who cares? If students are doing that and we say “this is a mistake, this is wrong”, then you’re actually saying “your culture is wrong. Your home is wrong, your parents are wrong, the way they speak is wrong.” So instead, let’s think of it as a translation, and instead of saying “this is wrong”, say “in standard English, we use the apostrophe when we mean possessive”, “in standard English, we don’t write ‘I could of’ with the OF , we write ‘I could have’ with an H. A. V. E.” I think that would be maybe a softer way of showing students that this is the way in which we want them to write.

Sometimes what we consider error are things that reflect a different variety of English. And sometimes what we see in error are just ticks that people have or things like using the wrong ‘there.’ I don’t think anybody’s doing that necessarily on purpose. I can bet most students know what ‘there’ goes where, but in writing something fast, it gets confused and forgotten and maybe they didn’t have enough time to edit. That’s not important; the most important part is the ideas, like I said, the attempt of writing in a genre and for a specific audience. There can’t be perfection, even when we’re asking our students to write for academic audiences; they’re gonna make little mistakes, and by focusing on that we’re taking away from all the learning that they are doing.

Faculty often express concern about balancing between helping students grow as citizens or community members and helping them prepare for professional success. What are your thoughts on this concern as a professor of rhetoric and writing?

I mean, I feel like I need to assume a lot of things to understand that as a binary. So, when you’re a citizen and a community member, what are your concerns versus when you’re a professional? You see what I’m saying? I guess, like community writing is different than professional writing?

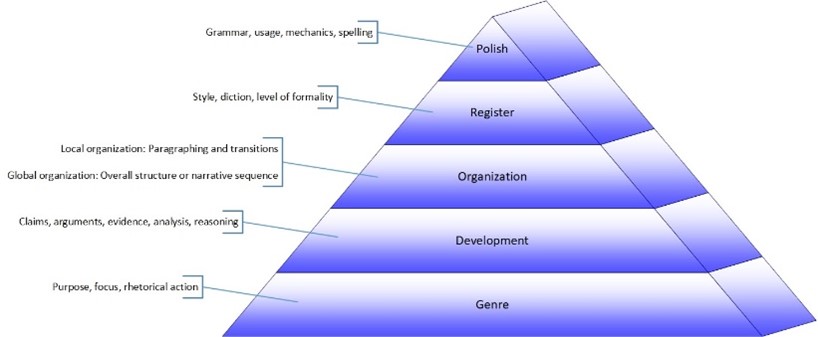

I think that professional genres are distinct. And I think that maybe that’s the approach. To really make sure that your students know how to write in their profession is to focus on genres and be specific about the genre in which you’re teaching, right, like “this is the genre of lab reports, this is the genre of academic articles” or whatever it is that you’re doing. But when we think about ‘citizenship’… I’m not a super fan of that word because of all its colonial baggage. But let’s define ‘citizenship’ as ‘involved, caring community members.’ How I’m seeing the binary is this: do we want to create engaged citizens that will again work for a better world or do we spend time professionalizing our students? How are those not the same thing? Because yes, we want to professionalize them in ways that are going to care for their communities, in all fields. We want to professionalize them in ways that are ethical; in ways that are community centered; in ways that are attentive to justice. And those are the same things that we want our citizens to do. They intersect. But the professional part –100% it’s important. We want our students to go into their jobs feeling comfortable enough to be able to succeed. So teaching genres as genres is, I think, a really great approach.

I think that this is something we struggle to think about as educators, because we want to do right by our students, and we want them to be prepared. But then if we just continue to replicate the dominance of academic English, then we’re never going to stop spinning the same wheel. If our students see that we’re talking about varieties of English, or at least about academic English as one variety… if they have that perspective when they’re the ones doing the hiring, it can spread and lead to more equitable language practices.

Hearing this discussion about different varieties and professional genres reminds me of the calls some writing scholars have made for code-switching or code-meshing pedagogies. Would you compare this to teaching students to code-switch?

I think there’s definitely some of that in approaching error as a translation issue. I think that’s a good approach, because we all learn to code-switch in a way, right? If I’m having an interview with you two, especially Alex because I know you, I communicate in a certain way, but if it was Peter [Betjemann, Director of the School of Writing, Literature, and Film] and Dean Rogers [College of Liberal Arts], I would communicate it a different way. We all do it; just for some of us, the code-switching, the two codes are more closely linked. Some of us are allowed to be a little bit more lax in our code-switching because of our skin color. For example, if you’re a black academic and you show up to your meeting with your department chair and you don’t code switch completely – I don’t know, I feel like you’re not allowed to do that as much as those of us who are white or white presenting.

So, yeah, I feel like that is a good approach to continue trying to see if it actually does what we want it to do, right? Especially outside of the writing classroom. Is it going to help us to be able to teach students about Standard English without completely devaluing how they are coming to our classrooms and where they come from? The cool thing about code-switching is that our students already know how to do it. They just haven’t really been purposefully asked to do it in their writing before. A black student who comes to predominantly white University is adept at code-switching – she already knows how to do it. Or a student who speaks Spanish at home, or Spanglish at home – they already know how to code switch.

Are there any specific resources that you would recommend for people to learn more about everything that we talked about today?

First, this book is awesome – it’s called Vernacular Insurrections by Carmen Kynard [available as an ebook through OSU Libraries], and it’s about a more expansive idea of literacy to literacies. Kynard looks at black protest and black student movements, social movements, as literacies that have affected the way that writing happens in the classroom and that have affected composition and literacy studies, but that are often not recognized as having done so. I think that this is a good book to read, especially in this moment where people are more willing to engage with black authors, black ways of knowing, and black knowledges. I also mentioned land-based literacies earlier – that idea comes from an open-access article by Gabriela Rios titled “Cultivating Land-Based Literacies and Rhetorics.” It’s a really great article and it’s very accessible, I think even to those who are not in the discipline of literacy studies.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any quick things, and I think it’s because considering different varieties of language and different literacies is not a quick fix or a quick practice. I think it takes soul-searching about your comfort level and your own biases. You have to come to terms with your own biases when it comes to language and literacy and students… and that’s sometimes not fun to do. And you have to really think about the why – why it’s important, what you really want to do for your students in the classroom, and whether you really want to put your teaching where your mouth is when it comes to diversity, equality, and social justice.

This interview is the first entry in WIC’s linguistic justice series. A review article in Winter 2021 and a Spring Lunch will continue to explore related topics.