Pollinator Syndromes

Pollinator syndromes are the characteristics or traits of a flower that appeal to a particular pollinator. These traits often help pollinators locate flowers and the resources (e.g. pollen or nectar) that the flowers have to offer.

Syndromes include bloom color, the presence of nectar guides, scents, nectar, pollen, and flower shapes. We can use these traits to predict what pollinators might be attracted to certain flowers or we can use these tools to guide us to pick the right plant for the right pollinator!

Bees, for example, are most attracted to flowers that have white, yellow, blue, or ultra-violet blooms.

Pollinator Syndromes for Bees & Butterflies

Table adapted from the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign

| Trait | Bees | Butterflies |

| Color | White, yellow, blue, UV | Red, purple |

| Nectar Guides | Present | Present |

| Odor | Fresh, mild, pleasant | Faint but fresh |

| Nectar | Usually present | Ample, deeply hidden |

| Pollen | Limited; often sticky or scented | Limited |

| Flower Shape | Shallow; with landing platform, tubular | Narrow tube with long spur; wide landing pad |

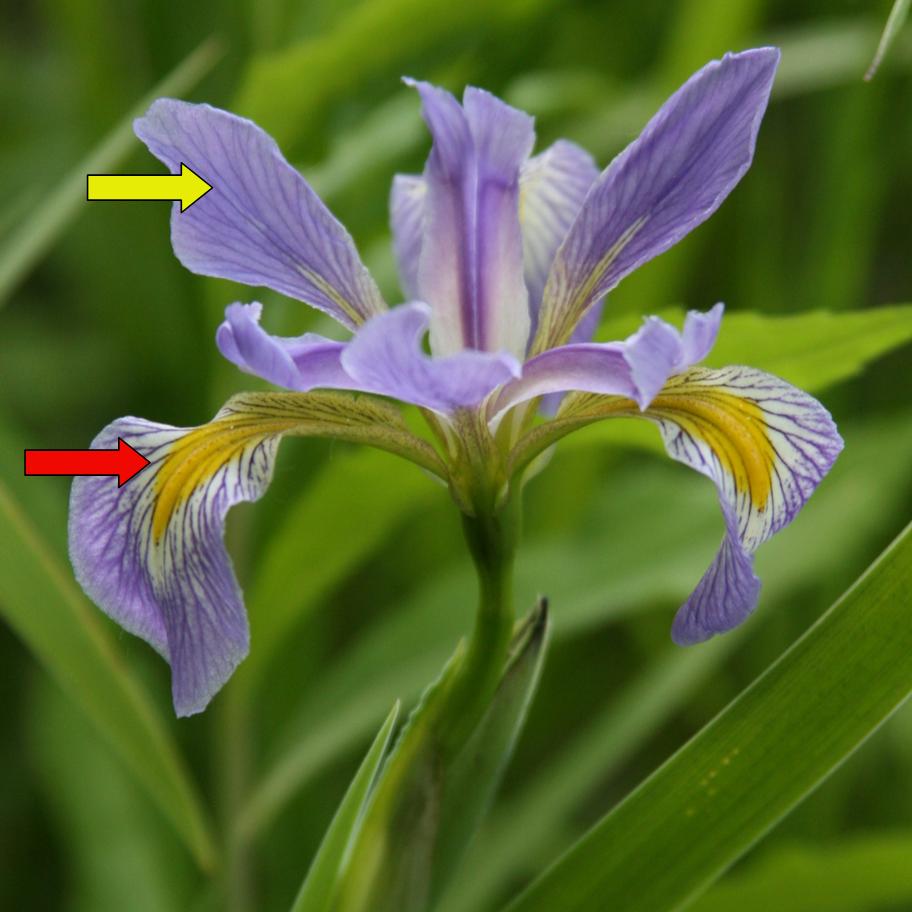

What are nectar guides?

Nectar guides are visual cues, such as patterns or darker colors in the center of a flower, that lead pollinators to nectar or pollen. These cues are beneficial to plants and their pollinators because they can reduce flower handling time, which allows bees to visit more flowers and transfer more pollen in a shorter amount of time.

Northern Blue Flag Iris (Iris versicolor).

The petals (yellow arrow) and sepals (red arrow) both have dark purple nectar guides. The yellow portion of the sepals may also be a nectar guide!

Image courtesy of Mike LeValley and the Isabella Conservation District Environmental Education Program

While the iris’s nectar guides are visible to humans and their pollinators, this is not always the case. Some flowers have nectar guides only visible in ultra-violet light. The video below shows how different flowers look to us (visible light), and simulates what the flowers look like to butterflies (red, green blue, and UV) and to bees (green, blue, UV).

What about pinks and purples?

Red-flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum)

It’s not uncommon to see bees visiting flowers that are colors outside of their typical pollinator syndromes. In the spring in Oregon, we see bees visiting red-flowering currants, many pink and magenta rhododendrons, plum blossoms, and cherry blossoms. Lavender, catnip, and other mint-family plants too are common on pollinator planting lists, but tend to have purple flowers.

Pollinator syndromes can help us understand these anomalies. These flowers may appear differently in ultraviolet light or may have strong nectar guides that encourage bees to visit them, despite how they look to us. Alternatively, these flowers might have rich reserves of pollen and nectar that draw bee visits.

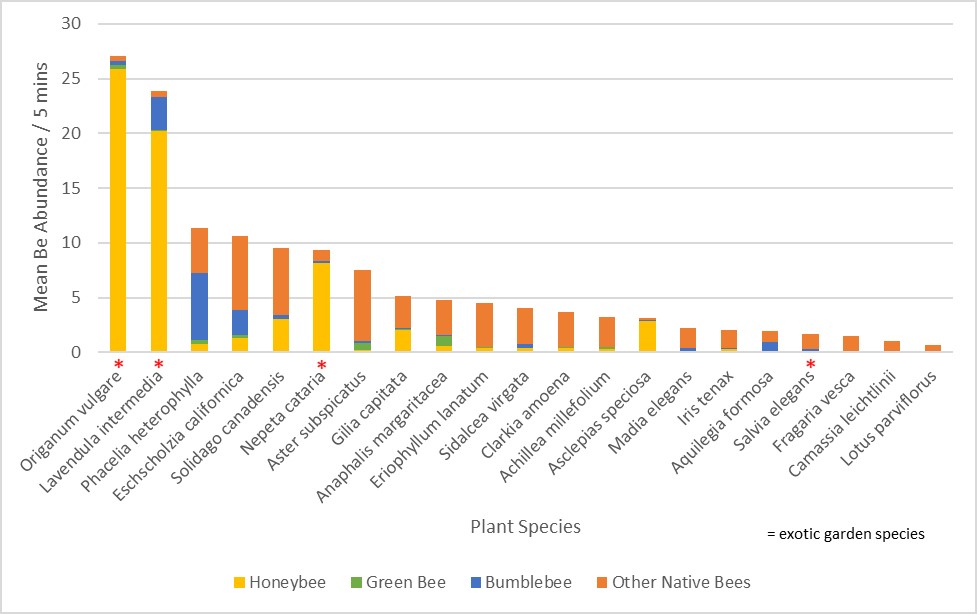

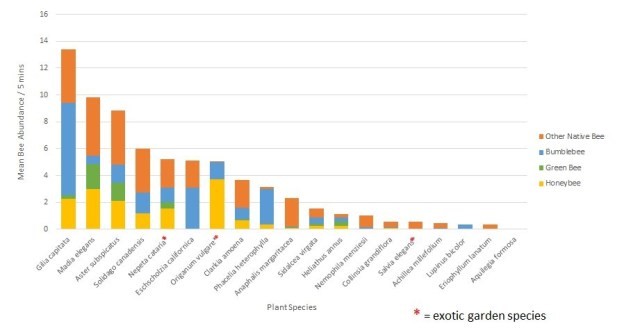

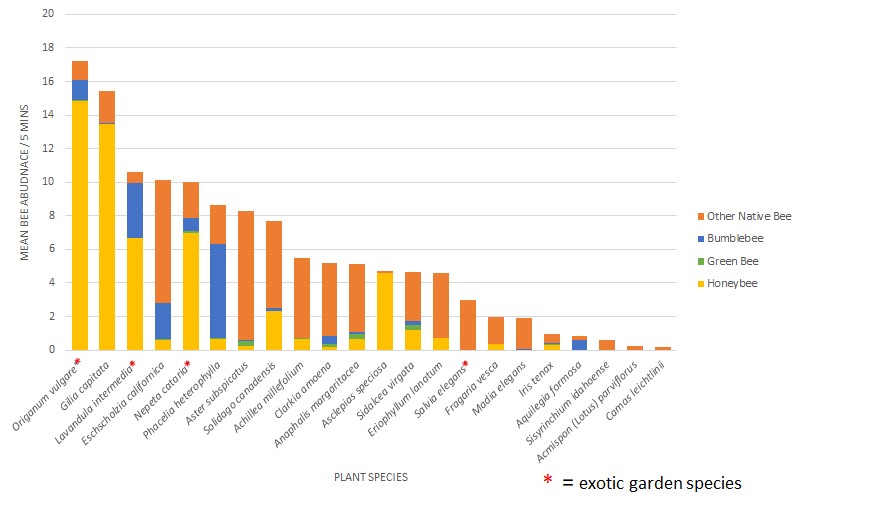

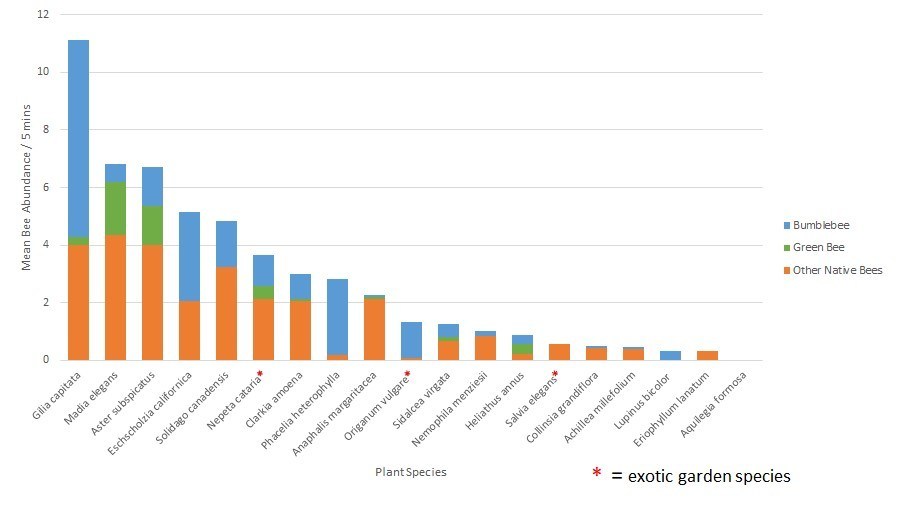

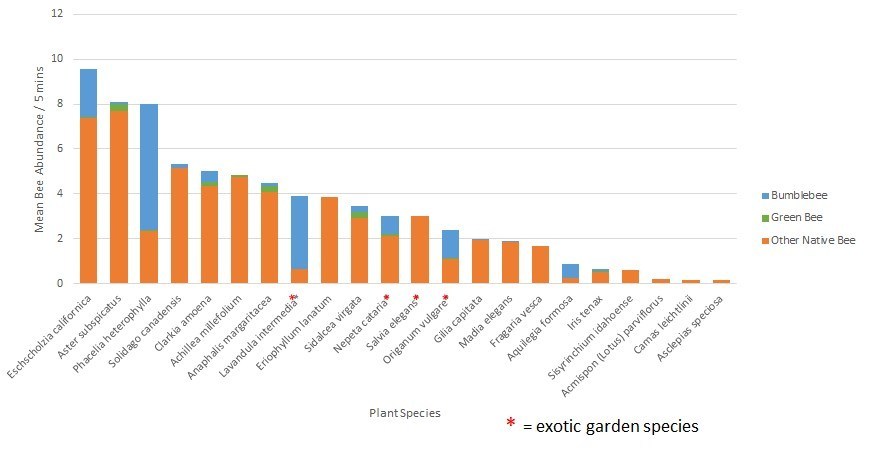

How else do we know if a flower is a good choice for bees?

Many people have developed plant lists based on personal observations, so there are many pollinator plant lists available to choose plants from. Many nurseries include pollinator attraction information with their planting guidelines too. While these are often based on anecdotal evidence, many researchers (including Aaron and I) are working to provide empirical evidence for plant selections.

To find native plants to attract bees and other pollinators, I recommend starting your plant selections by checking out your local NRCS Plant Materials program.

Many extension programs may also have regionally-appropriate plant selections! Here is the link to Oregon State’s list of native pollinator plants for home gardens in Western Oregon.

When you’re ready to buy some plants, make sure to check out this blogpost by Aaron.