by Alexander Mahmou-Werndli, WIC GTA

This year’s annual fall kickoff event, “Responding to Student Writing,” featured two excellent speakers: Tianhong Shi and Dr. Mary Nolan. Tianhong has been an instructional designer working in higher education since 2006 and at OSU Ecampus specifically since 2014. She is currently a PhD candidate in Educational Leadership at the University of Cumberlands in Kentucky. Mary Nolan is a senior instructor in the anthropology program who has been teaching Ecampus courses for twelve years. Among these is the Anthropology program’s WIC course, which she has been teaching in its online format for the last eight years. A special thanks is also due to Ecampus’s Katherine McAlvage, whose steady hands managed and coordinated the Zoom event.

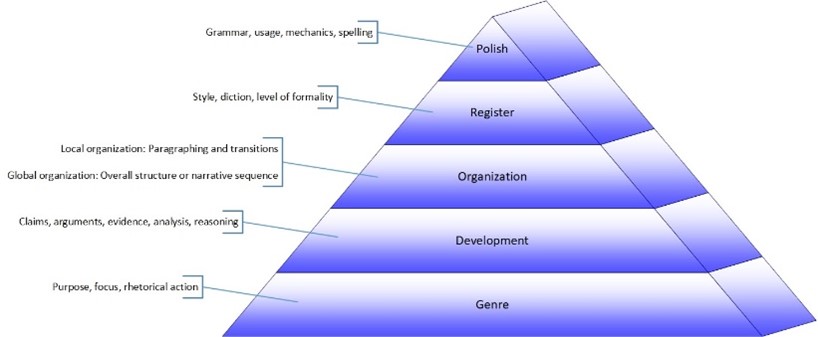

WIC Director Sarah Tinker Perrault kicked off the event by providing a general framework for organizing responses to student writing. As a means of distinguishing between revising, editing, and proofreading, she referenced the hierarchy of rhetorical concerns (pictured below).

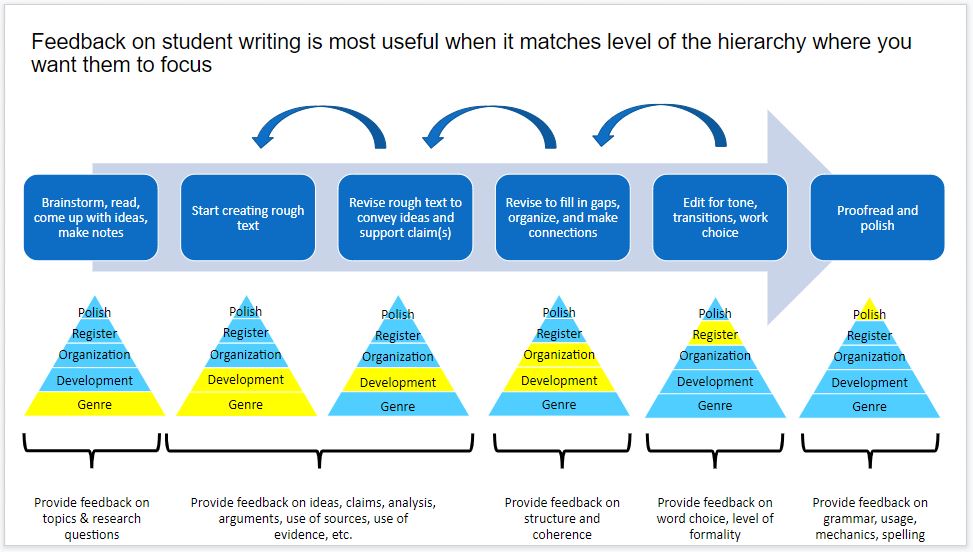

Feedback on student writing is most useful when it matches the level of the hierarchy on which the instructor would like them to focus. Mapping this hierarchy onto the writing process can thus help identify concrete points for intervention on global-scale concerns like genre, ideas, and use of evidence as well as local-scale concerns like polish and editing.

Following Sarah’s presentation, Tianhong gave an overview of several foundational teaching paradigms: backward design, Bloom’s taxonomy, and the brain targeted teaching model, each of which has pronounced implications for responding to student writing.

Backward Design

Backward design is an orientation of pedagogy that begins with identifying learning outcomes and works backward to generate assignments, activities, and lectures rather than the other way around.

This model is particularly relevant when deciding what kind of feedback to give at each stage of a writing project. If your responses to student writing are meant to help students refine their presentation of content and meet the genre standards of a particular assignment, your students will need to receive formative feedback that sees their assignments as works-in-process and facilitates continued revision. If your aim is to simulate what happens when disciplinary or professional work is submitted (e.g. to a journal or professional readers), responding in summative feedback might be more appropriate.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

After her discussion of backward design, Tianhong moved to Bloom’s taxonomy. Rather than presenting the taxonomy as a familiar hierachy, though, she modified it to better reflect the pedagogical goals of WIC courses by presenting the six cognitive activities as an interwoven loop.

This interconnectedness rings particularly true for peer review, which we as instructors often use to accomplish multiple pedagogical goals at once. In order to respond to one another’s writing, students must first analyze their peers’ texts to evaluate how their writing is meeting the assignment’s outcomes and requirements. This activity prepares students for the cognitive demands of creating or revising their own texts, and peer review encourages students to reflect, self-analyze, and revise in a recursive process.

The Brain-Targeted Teaching Model

Finally, Tianhong moved to the brain-targeted-teaching model, the model which directly informs her own research. Neuro-pedagogy asks teachers to take into account the physical and cognitive factors which affect students’ learning processes.

Considering student’s emotional climates and physical environments when presenting feedback that carries the potential to affect students’ motivation and self-image as writers seems all the more relevant during the remote learning brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching for Mastery and Teaching for Application connect to WIC course’s combination of content focus and disciplinary writing instruction, respectively, but in order to help students engage in evaluative learning Tianhong suggests not only responding to student writing but assigning reflective activities which ask students to evaluate their own writing.

Following some breakout discussions, Mary spoke next. She shared wisdom from her experience as an anthropology instructor, including the importance of designing a course so that students begin writing early and often, receive feedback, and have opportunities to revise and try again. Her description of her own writing process, beginning with rough drafts and revising before polishing her grammar, reminds us how important it is that we reinforce a revision mindset via the feedback we give. It is well documented that providing extensive feedback on grammar and punctuation can overwhelm students, while focusing too early in the process on surface errors will actually discourage substantive revision by leading students to believe fixing surface errors is enough to finalize a draft.

Perhaps most helpfully, though, Mary’s presentation emphasized how writing serves as a mode of thinking both in and outside the classroom. To this end, she first identified a recurring problem: her students’ tendency to “hide behind” field-specific terminology and the names of prominent scholars. Mary then provided several samples of ways writers using “hit-and-run” quotation tactics. She then role-played responding to such writing, showing how she would ask students to explain the concepts and quotations to her as though she were an uninformed outside reader, thus prompting them to articulate the significance of such evidence to their fellow novice anthropologists. Her examples of feedback to writing, therefore, modeled not only effective use of evidence for students but also how we as instructors can guide our students to greater content understanding through a focus on their writing.

A recording of the event is available on WIC’s website.