Olivia Williams | 4th-year PhD Candidate in Geology

The week of April 8th 2024, I traveled to the NSF Ice Core Facility (ICF) in Lakewood, Colorado to help process ice cores from this year’s field season. Together with Liam Kirkpatrick (PhD student, University of Washington) and Fairuz Ishraque (PhD student, Princeton), I had a fun, fascinating, and very cold week experiencing the logistics that make ice core science possible.

The reason for our trip was to help wrangle samples for the Center for Oldest Ice Exploration (COLDEX). This multi-university center is helping to extend our ice core record of past climate beyond our current 800-thousand-year timeline. The ’23-’24 field season—COLDEX’s second—saw researchers and drilling technicians return to the Allan Hills, a fascinating site where very old ice has been forced closer to the surface by underlying topography. They drilled about 140 meters of 9.5-inch-diameter cores with a blue ice drill, plus 90 meters with the 3-inch Eclipse drill and several more boxes of hand-augured ice. This ice was bagged, labeled, and packed in boxes of fresh Antarctic snow for the long journey back to the United States.

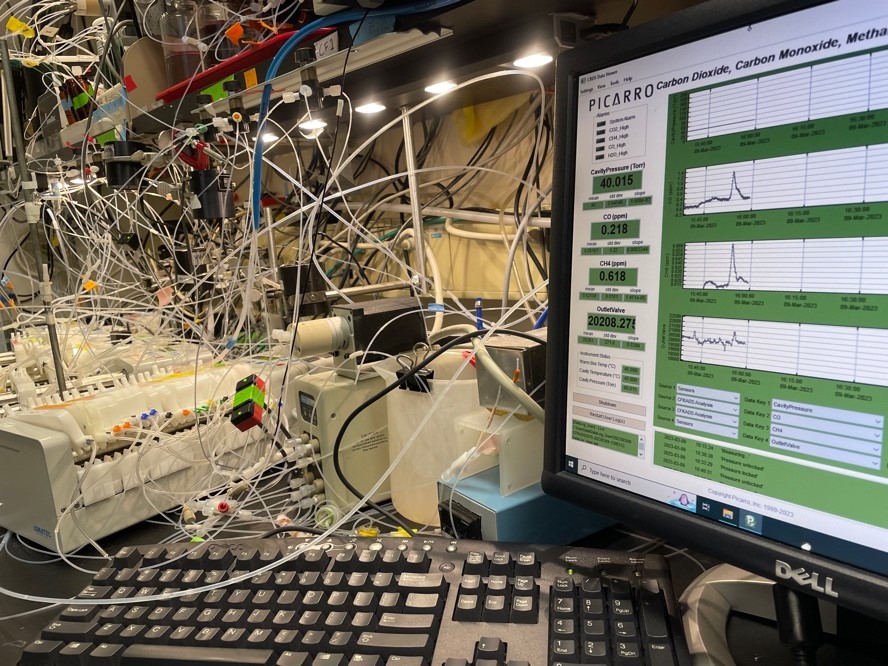

Now that it has arrived at the ICF, the ice needs to be cut up into smaller samples and shipped to labs across the US to determine things like its age and gas content. Three CEOAS early-career researchers who were on the field team (Julia Marks Peterson, Asmita Banerjee, and Abby Hudak) will be among those measuring carbon dioxide and methane content, dust particle count, and water isotopes. However, before any processing can take place, the ice must be unpacked and archived properly at ICF. This was the purpose of our visit.

Each morning, we left our rental and drove to the federal campus in Lakewood. Passing through the security checkpoint, coffee balanced in my lap as I flashed my passport and explained we were scientists visiting the Ice Core Facility, I felt like I was in a TV show. Then we’d drive on, past mysterious unlabeled structures and parking lots full of police and logistical vehicles, until we arrived at an enormous building with rippling vaulted roofs. I’m told it was initially a munitions factory. Among other things, it holds the USGS Core Research Lab, which in turn manages the ICF. We’d park and head inside to drop our stuff by the folding tables set up in the large warehouse space and go over our plan for the day.

The first order of business: bundling up. The storage room where we would retrieve boxes and shelve cores was -36°C (-33°F), and the work room where we spent most of the day was a comparatively balmy -25°C (-13°F). ICF has a variety of freezer gear to loan. However, like most people I know in this field, I like to travel with my own tried and true base layers. Over my t-shirt and leggings, I would don long underwear, a wool-blend sweater, and a thick second pair of socks. Then I’d put on the ICF-issue insulated coveralls and work boots. I brought my own glove liners, beanie, and muffler, and borrowed thick gloves and a faux fur-trimmed hat with ear flaps. The only skin left exposed was around my eyes—and that would be red and stinging like a mild sunburn by the end of the day.

Once we were physically and mentally prepared to enter the freezer, some of us would head to the back storage room with a list of which core depth intervals were in which boxes. After we located the right boxes and lifted them onto dollies, we could wheel them out to the work room and open them up, undoing the tight straps used to secure them on their long trip north.

Each box held several pieces of ice core, each in their own labeled plastic bag. Some of them were the full meter-long pieces we prefer to drill. Others were smaller, fractured segments that had broken apart during drilling. The ice at the Allan Hills can be challenging to drill in whole pieces due to its unusual stratigraphy and physical properties. Either way, the pieces were packed in now-solidified snow, so we would hack and chip at the icy chunks until we could peel them out and get at the samples below.

It was a challenge to dent the snow without chipping or damaging the ice it contained. Excavating the core sections felt like doing one of those children’s paleontology kits where you dig “fossils” from a hard sandy matrix with a dowel. Remember, we were working in a freezer, so any snow that ended up on the floor would become a slip hazard until it was swept up. We had to keep snow in rolling bins that we emptied in the parking lot at the end of each day.

Once retrieved, the ice could be arranged on the counters of the work room in depth order, ready to be re-shelved in the back room for easy access during upcoming sampling.

On days when I wasn’t doing the physical labor of slinging core boxes, I was learning how to use Liam’s instrument for electrical conductivity measurements (ECM). This technique involves dragging a pair of electrodes down a length of core to measure changes in the direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) conductivity, which are affected by changes in the ions present in the ice. AC is sensitive to a wider range of ions, and DC largely measures acidity. Ionic content can reflect the presence of volcanic ash, dust, or other impurities. By measuring multiple tracks across the width of the core, you can see whether layers are horizontal or angled. This gives us critical information about how to align sampling and how much we can trust the stratigraphic order at particular depths.

Being the ECM assistant mostly meant babysitting the electrodes to make sure they made good contact with the ice. I had to flag any places where they went over a crack or chip so that Liam wouldn’t interpret the decrease in conductivity as a “real” signal. I also learned how to use the PlayStation controller rigged up to the instrument to tell it where the corners of the slab were. There was a fun issue where pressing anything besides the joysticks would cause Liam’s program to crash—something I did more than once because I’ve only played Xbox and that controller is configured differently.

While heavy lifting in the freezer isn’t exactly fun, it’s certainly preferable to standing still. Every time I had to take my gloves off to enter metadata for the next slab I could feel my mental timer ticking down faster towards break time. After 30 minutes or so of watching the ECM I felt the concrete floor draining the warmth out of my feet through my boots. At a certain point the sensation switches from cold to a pure ache that radiates up the bones of your shin. When that ache starts to fade, you’re overdue for a break; as the ICF folks frequently say, “don’t accept numbness!” One especially high-focus day I accidentally let some toes go numb. It felt like I had a few cold little pebbles in the toe of my boot. Down that road lies frostbite.

The more you try to push through the cold, the longer a break you have to take. Pacing helps, as does dancing. A few times I looked up from boogying next to the ECM to see that someone on their break was laughing at me through the window. It’s still better than standing still, which is what your brain tries to convince you to do. The energy preservation instinct is strong.

Freezer work also spikes your appetite. Right outside the freezer door sit jellybeans, gummy worms, pringles, and oreos to grab by the handful whenever you step out. I destroyed some lunches that would normally be two meals for me, including an incredible plate of fried chicken and jalapeno cheddar waffles at the end of the week.

We made great time on our goals. Although I’m not officially a part of COLDEX research, it felt nice to know that we were making things easier for the folks who will be there for the summer core processing line. It’s a huge privilege to handle ice that could be upwards of 6 million years old, looking at the little bubbles and knowing that they contain atmospheric air from so long ago. I also learned a ton about how the ICF staff manages new ice arrivals, sample requests, archival priority, and all the little administrative questions at the back end of ice core research. I certainly appreciate all the logistical support that goes into projects like mine.

Despite the chill and the chapped lips, I would absolutely return to ICF in the future for more ice processing. The staff are outstanding at their jobs and great company. And, of course, it’s a perfect opportunity to snoop on several decades of archived ice!