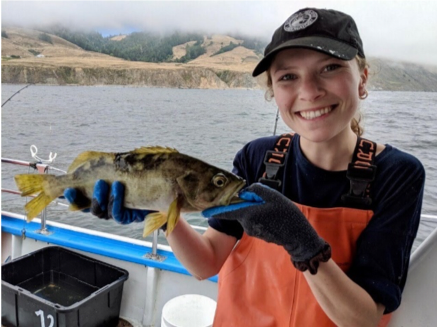

Laura Vary, M.S. student in Marine Resource Management

Beginnings of a scientist

I first became a scientist when I was four years old. I was crouching beneath a large pine tree in the woods of my backyard with my father standing beside me. We were inspecting an oblong, dark brown conglomeration. My dad explained that this mysterious thing was an owl pellet, likely excreted by one of the screech owls inhabiting our property. He palmed the pellet and we walked back to my house along the wooded path, my mind expanding as he described all that the little pellet could contain.

Back in our garage, my father showed me how to carefully break apart the pellet using tweezers. He pulled out small rodent bones, teeth, and other unidentifiable fragments tangled in the coarse hair that held the pellet together. We dissected many of these in the months that followed, transforming my backyard into my first field site. My interest in ecology grew as I watched the dynamics of robins, cardinals, foxes, and chipmunks in those woods. They introduced me to basic biology as I found treasures including a complete, bleached possum skeleton and an intact still-born coyote pup. My biochemist father taught me all he knew about our woods during frequent walks in the evenings, stoking my enthusiasm and helping me to learn that the world of science could be mine.

Though I lived inland near lakes and rivers teeming with small spotted sunfish and bass, I was drawn to the craggy granite shoreline of Maine’s coast. I would rock-hop away from my mother as she read to seek out hidden tide pools that burst with barnacles and mussels and small periwinkles. By sixth grade I was determined to become a marine biologist.

to another coast, far away

My mission to become a marine biologist led me, surprisingly, to the drought-stricken Central Valley of California where I studied marine and coastal science at the University of California at Davis. I was immediately drawn to the school after learning about UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory. Strategically located at the site of one of the most productive areas of the California coast, Bodega Marine Lab houses all varieties of innovative University of California undergraduate and graduate marine ecosystem research. With urging from my father to “follow the research” and extensive emotional support from my mother, I moved 3,300 miles away from my family.

I joined my first undergraduate research project in the spring of my freshman year in the Ecology and Evolution Department with the Wainwright Lab studying the morphological evolution of teleost fishes. I traveled to the Smithsonian Museum’s Collections Facility in Maryland with a small group of my peers, and together we measured preserved specimens of Teleostei fishes. These measurements, and others taken by more undergraduates in following years, produced one of the largest public databases of linear measurements of fishes available today. This work resulted in the presentation of my first research project utilizing a subset of these data at the 28th Annual Undergraduate Research Conference.

Then, after a year-long digression in terrestrial plant ecology, my first significant experimental failure, and the completion of physically exhaustive biology courses, I finally arrived at Bodega Marine Lab in August of 2018. I studied coastal and biological oceanography and assisted with research in Steve Morgan’s planktonic fisheries ecology lab. I counted fish larvae and eggs and became endlessly fascinated with the expansive world that fit within the view of my microscope. I returned to this lab after graduation in 2019 to become a paid research technician. In this dream role I learned identification of invertebrate larvae, how to distinguish one species of krill from another, and organized a science crew and team of volunteers to evaluate marine protected areas off the Sonoma Coast. The Morgan Lab became my second home; I understood my priorities as a researcher and progressive member of a new wave of scientists and determined what my future after graduation would look like.

From marine biologist to marine resource manager

Upon reflection of my undergraduate education, I realized that solving complex matters like sustainable ocean management and climate change requires an interdisciplinary framework. Furthermore, I learned that the waves of change I wanted to make would be more difficult to achieve with my Bachelor’s degree alone. The recognition of these goals led me to Oregon State’s research-focused yet extremely interdisciplinary marine resource management program. In the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences I will work with Dr. Lorenzo Ciannelli in his fisheries oceanography lab. Using fish plankton data, I plan to research the ability of fishes like halibut, cod, and pollock to alter the timing (phenology) and location (geography) at which they spawn. I strive to understand the biological flexibility of these species and how it relates to the future of their populations, reliant commercial and Indigenous fisheries, and the larger marine ecosystem. I am driven by the need to understand what confers resilience in fish populations, and how we – as stewards – can learn from traditional native practices, historical environmental dynamics, and robust predictive models to create sustainable ecosystems and restore balance in the ocean.

My path in science has always been driven by a clear goal to promote sustainability and revitalization within our global ecosystems. I hope that more people find room for research and science in their daily lives as this goal intersects so many fundamental aspects of human life. A common misconception for many is that scientists are highly trained individuals that dedicate their lives to research… we are not. We are inquisitive people that look at our world, make observations, and ask questions, just as I did when I was young. I want more people to understand that their voices and actions are deeply influential in the scientific world, and I will dedicate my future in research to ensuring the inclusivity of academia, management, and conservation. Science needs everyone!

Follow Laura on Twitter @resultscan_Vary