In Southern Oregon’s scorching summers, it can be hard to imagine a vibrant garden that doesn’t rely on constant irrigation. But at the Jackson County Master Gardener Waterwise Garden, colorful blooms, pollinator habitat, and year-round interest prove that climate-resilient gardening can also be beautiful. Designed to showcase low-water native and ornamental plants, this demonstration garden at the OSU Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center is inspiring visitors to rethink what’s possible in a drought-prone climate. OSU Extension Master Gardener volunteer Pete Livers and Master Gardener Coordinator Grace Florjancic share what they’re learning—and teaching—about gardening in a hotter, drier world.

Waterwise Garden in Central Point

A conversation with OSU Extension Master Gardener volunteer Pete Livers and Master Gardener Coordinator Grace Florjancic

What was your garden like prior to any changes you’ve made for climate resiliency?

The Jackson County Master Gardener waterwise garden set out to show how you can still have plenty of colorful blossoms and year-round interest while saving on water usage. This garden was designed with a mix of low water usage native and ornamental plants. There are many pollinators that visit this garden throughout the year like bumblebees, honeybees, and butterflies.

What issues did you find you were facing regarding climate change impacts in your garden?

Frequent irrigation in our intense summer heat has become an issue for many gardeners. Using drip irrigation has helped us be more efficient with water usage but low water use plants is another step towards reducing the need for constant summer irrigation.

What plants have you changed to help with climate resilience?

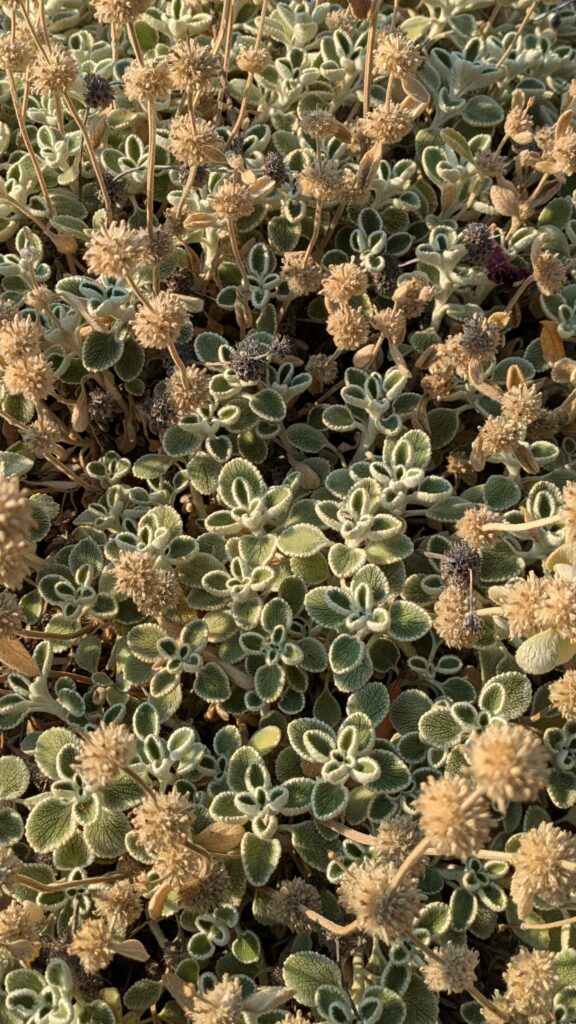

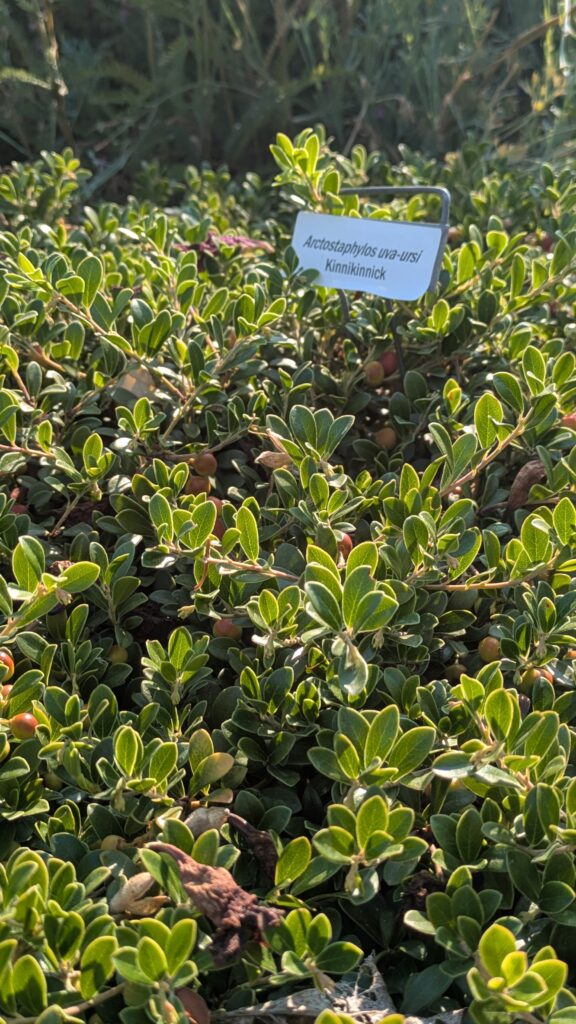

Some of the native plants like poppies and yarrow wander out of their desired areas. From a structured garden perspective, some of these plants have been removed to keep the desired appearance. Low water usage irises recently replaced some yarrow to fill out the irises currently in the garden bed for a fuller appearance. The native California fuchsia, buckwheat, and Kinnikinnik play nicer with their neighbors in a formal garden setting.

What techniques have you changed to help with climate resilience?

Master Gardener Pete Livers is the new team lead for the waterwise garden. As a newcomer to the garden, Pete has found the main challenge to be learning which plants are very drought tolerant and which ones are just low water plants. Pete has been keeping a careful eye out for plants that show signs of stress like curling and wilting leaves. To not overwater the extreme drought tolerant plants, he has resorted to hand watering the individuals that show signs of drought stress.

Are you anticipating future changes you plan to make?

No major changes for our garden at the moment. Plants may get occasionally swapped out for color, size, or other desired attributes to keep the garden fresh and exciting.

Have you received feedback from others regarding the changes you’ve made?

Many people are surprised at how many flowers and pops of color are in this waterwise garden. Often people have an image of rocks green cacti and succulents in mind for a waterwise garden. We wanted to show another way to create a waterwise garden with blooms each season.

Do you have any specific resources you’ve used in making the decisions for the changes you’ve made?

Some helpful resources for gardeners designing a waterwise garden include native plant lists such as Gardening with Oregon Native Plants East/West of the Cascades and the Firewise Plants for Home Gardens publication. Check with your local nurseries to see if they have a list of their available native plants and low water use plants for sale.

What would you tell other gardeners who want to make changes in their gardening to create more climate resilience?

Our summers in Jackson County turn brutal for a full sun garden quickly and some irrigation is still needed once or twice a month in an established waterwise garden like ours. New plants need to be gently acclimated to low water conditions and individually watered until established. A common mistake is expecting a young plant fresh from the nursery to be able to survive a drought before becoming established. Grouping your low water use plants together makes watering much easier than having them mixed between water-loving plants.

How are you using your climate resilient garden for teaching or outreach events?

We have hosted garden tours for local gardening clubs across the county where we discuss each garden and share ideas. Last summer, the local news station did a feature on waterwise gardens and included footage from our garden!

Anything else you’d like to share?

Some of the plants Pete wanted to highlight are the arrow leaf buckwheat for interesting foliage and dramatic white blooms and the purple cooking sage for the unique purple to green fade the plant has. A well designed waterwise garden still has plenty of interesting leaves, blossoms, colors, textures, and habitat for the local critters.

Established in 1994, the Jackson County Master Gardener Demonstration Gardens feature fifteen different gardens that are used to teach the art and science of gardening through the OSU Extension Master Gardener Program and to the community at large. The Demonstration Gardens are located on the grounds surrounding the OSU Extension office in Central Point, 569 Hanley Rd, Central Point, OR 97502. The public is welcome to take self-guided tours Monday through Friday between the hours of 9-5 p.m.

Explore one of Oregon’s 50+ Master Gardener Demonstration Gardens—realistic, regionally adapted spaces that showcase what thrives in your local conditions. Find a demonstration garden near you.

This story is part of Garden Future, an OSU Extension Master Gardener outreach project dedicated to conversations and action for gardening in a changing climate.

What are you seeing in your garden? What changes are you making? We invite you to join the Garden Future conversation by answering three quick questions. At the end, you’ll have the option to sign up for our Garden Future newsletter and stay connected with stories, resources, and tools to support climate-resilient gardening in your community.

Photos by Grace Florjancic