David P. Turner

January 20, 2025

Earth system scientists tend to think a lot about the future. Their simulations of Earth’s near-term future ̶ based on projections of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions ̶ suggest dramatic changes in the climate that will stretch our human capacity to adapt. For the purposes of climate change mitigation, their assessments indicate that the current trajectory of climate warming could be moderated significantly by collective action to reduce emissions.

Neoliberal economists on the other hand do not think much about the future. According to neoliberal economic theory (and practice), the future will take care of itself. Individual purchasing choices within a free market economic system will purportedly bring any negative aspects (externalities) of economic activities under control and correction. Therefore, governmental interference in the economy is the road to ruin.

If Earth system scientists are right, and neoliberal economists are wrong, humanity is in big trouble.

A neoliberal economy is a free market economy ̶ one in which supply and demand reign supreme (i.e. market fundamentalism). Associated public policies include limited taxation, limited governmental regulation, antagonism to organized labor, private ownership of common resources, and cheap credit to promote investment. The liberal part of the term refers to concern for individual freedom from governmental control, hence favoring little regulation and low taxes. The neo- part refers to the widespread adoption of hyper-liberal economic policies around the world beginning in the 1980s (e.g. the Reagan and Thatcher administrations). Besides insuring individual freedom, the theoretical upside of neoliberal economics is strong growth in gross domestic product (GDP) and this “rising tide lifts all boats”.

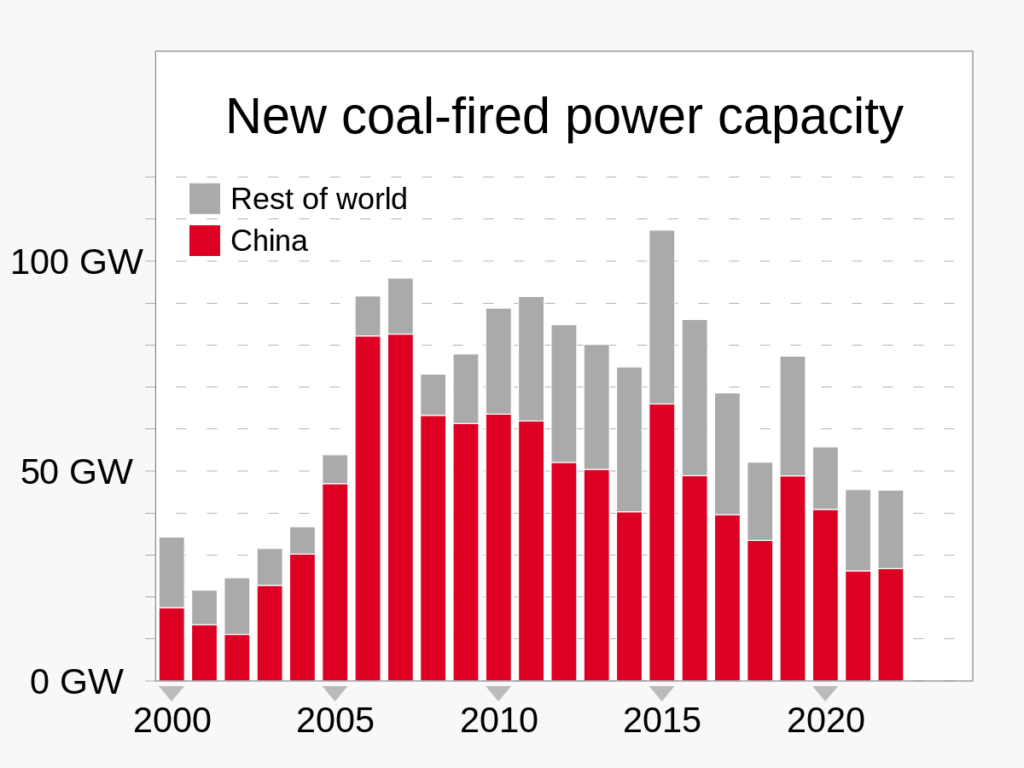

However, with respect to the future global environment, neoliberal economics has two long-term pernicious effects. The first is that the neoliberal stance against regulations and taxation allows capitalist entrepreneurs to avoid paying the environmental (and social) costs of production. CO2 emissions into the atmosphere – a global commons – from the combustion of fossil fuels for energy is an iconic example. CO2 is emitted into the atmosphere in the course of energy generation, but the costs of the emissions ̶ in the form of current and future impacts of climate change on human welfare (e.g. sea level rise) ̶ are paid by people subject to climate-related disturbances the world over. Failure to link fossil fuel combustion to its negative environmental impacts hinders the necessary societal effort to reduce emissions.

A second flaw of neoliberal economics is that the prized growth of the economy places increasing demands on natural resources, e.g. the atmospheric capacity to cleanse itself. The neoliberal assumption is that resources are unlimited if the price is right. But on our densely populated planet, many natural resources are being overused and degraded. In the cases where neoliberal economists do demonstrate concern for the future of the environment, the policy response is usually to put the burden for mitigation on the consumer. If someone is worried about climate change, they can buy an electric vehicle, and anyone not worried about it can buy a gasoline vehicle.

A primary alternative to neoliberal environmentalism is to include corporate and public institutions as responsible parties in addressing the negative environmental consequences of the economy on the environmental commons. These bodies operate at the scale required and have the resources to study the future and plan appropriately. Although state capitalism is perhaps not something to be emulated uncritically, China has recently demonstrated that if you want to rapidly reduce gasoline consumption, the government can intervene in many ways to make it happen without wrecking the economy.

Environmental sociologists refer to the process of Ecological Modernization (EM) as a path to governance where environment problems are addressed through policy changes and technological improvements, all in the context of modest economic growth. EM is not revolutionary systemic change to the capitalist economic system. It is more like continuous tinkering with policy (e.g. tax policy and pollution standards). EM is a form of cultural evolution that follows the model of biological evolution. Just as genetic variation provides the basis for natural selection in biological evolution, various policy alternatives provide the basis for political decisions in cultural evolution. Of course, it helps to have public forums, informed citizens, engaged politicians, and forward-thinking leadership.

Here, I’ve referred to the future-oriented aspects of Earth System Science and Neoliberal Economics. However, there is another whole discipline ̶ Future Studies ̶ that explicitly concerns itself with caring about the future. One of its common topics is scenarios for the human enterprise on Earth, be it self-induced environmental change beyond our ability to adapt, toxic political systems leading to collapse of civilization, or establishment of a sustainable, high technology, global civilization. Whether Future Studies is more at home in the Social Sciences or the Humanities is debated, but it is certainly a form of post-normal science, i.e. the practitioners commonly derive conclusions about public policy from their analyses.

Our primate brains may not be particularly well designed to think in terms of the global spatial scale and the multigenerational temporal scale. Nevertheless, we find ourselves in the Anthropocene era and we must accept our responsibilities for deliberately acting at those scales. Dogmatically clinging to market fundamentalism will not do the job.